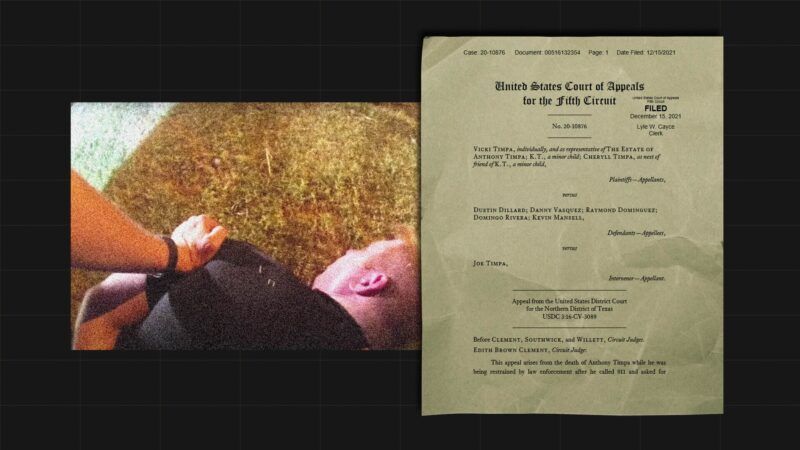

Tony Timpa Died After Cops Kneeled on His Back and Joked About It. A Court Says His Family Can Sue.

The officers originally received qualified immunity, meaning Timpa's estate had no right to state their case before a jury.

Until last month, Tony Timpa's family wasn't allowed to sue the police officers who allegedly caused his death by pinning him to the ground for about 15 minutes while he begged for help. Those cops had been given qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that insulates various government officials from scrutiny in civil court if the way they allegedly misbehaved has not yet been "clearly established" in some prior court ruling.

But in December the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit struck down the district court's decision, thus allowing Timpa's family to make their claims before a jury. That right—to state your case before a panel of your peers—is easily taken for granted. But victims of government abuse face a herculean uphill battle before they're permitted to do so.

On August 10, 2016, Timpa, who was 32 when he died, called 911 and asked for help. He had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorder, but he was off his medications that day and had taken cocaine. The Dallas Police Department (DPD) officers who responded to him—Sgt. Kevin Mansell, Senior Corporal Raymond Dominguez, and officers Dustin Dillard and Danny Vasquez—were aware of this: The 911 operator told them, and Timpa himself admitted it.

The cops put Timpa on his stomach, cuffed his hands and ankles, and kept him subdued in the prone position for more than 14 minutes. Vasquez pressed his knee into Timpa's back for the first two minutes and Dillard did the same for the entire duration, even after Timpa had calmed. "Help me!…You're gonna kill me!" he shouted. He became non-responsive for the last three minutes, and later he was pronounced dead.

On the body camera footage, the officers can be heard making light of his apparent loss of consciousness. Asked if Timpa was still breathing, Dillard responded "I think he's asleep!" and said that he heard him "snoring." Dominguez and Vasquez then joined in, joking that Timpa was a schoolboy who didn't want to go to class but could be lured out of bed with some "tutti-frutti waffles."

The 5th Circuit was not convinced by the lower court's decision to shield the men from a jury. "DPD training instructed that a subject in a state of excited delirium must, 'as soon as possible[,] [be] mov[ed]…to a recovery position (on [their] side or seated upright),'" writes Judge Edith Brown Clement, "because the prolonged use of a prone restraint may result in a 'combination of increased oxygen demand with a failure to maintain an open airway and/or inhibition of the chest wall and diaphragm [that] has been cited in positional asphyxia deaths.'" She also notes that the training explicitly says that a subject suddenly becoming unresponsive is a sign that he may be dying.

But an officer's own training is not enough to overcome qualified immunity. A victim must find a closely aligned court precedent, as if cops are more likely to read case law texts than their own training materials. (This is why a group of Denver officers were given qualified immunity for searching a man's tablet without a warrant and attempting to delete a video of them beating a suspect, despite their training that this violates the First Amendment.)

Fortunately for Timpa's family, there is a precedent that applies here. "Within the Fifth Circuit, the law has long been clearly established that an officer's continued use of force on a restrained and subdued subject is objectively unreasonable," says Clement. In case you were wondering just how granular qualified immunity can be: The officers had convinced the lower court that none of those precedents applied because they didn't pertain specifically to putting a knee on someone's back.

"This opinion gives cause for optimism and pessimism," says Easha Anand, Supreme Court and appellate counsel at the MacArthur Justice Center and an attorney for Timpa's estate. "The cause for optimism is the 5th Circuit has reiterated now, as a doctrinal matter, [that] if the only difference you can find between case one and case two is the kind of force being used, that's not good enough." On the pessimistic side, the district court's decision "was not pulled out of left field," she says. Whether or not an alleged victim gets the privilege to go before a jury very much depends on which judges hear his case and how they choose to define the level of specificity required to "clearly establish" a constitutional right.

Another reason for pessimism: The government has the power to drag out such suits with appeal after appeal, as months become years, while victims wait for the chance even to ask a jury if damages are appropriate. Earlier this week, the city of Dallas moved to prolong it further, requesting that the case be re-heard, a plea that is rarely successful. In their petition, the city's lawyers argue that since Timpa died before George Floyd ignited a national conversation around the prone restraint, they couldn't have known that what they did was excessive, despite the training that taught them it was excessive.

"I don't pretend that anything that can happen in a courtroom is going to provide solace for [the family's] pain," says Anand. "But I hope that at the very least, Judge Clement's opinion makes it so the family feels like some court has heard what happened and has understood it as a profound injustice." We'll see if the next one agrees.