Supreme Court Rebuffs Attempt To Open Up Access to Classified FISA Court Reports

Do Americans have a right to know the extent that the government surveils them?

For nearly a decade, activists have been trying to get the federal government to determine how much a secretive surveillance court can keep its conclusions out of the public eye. Today the Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

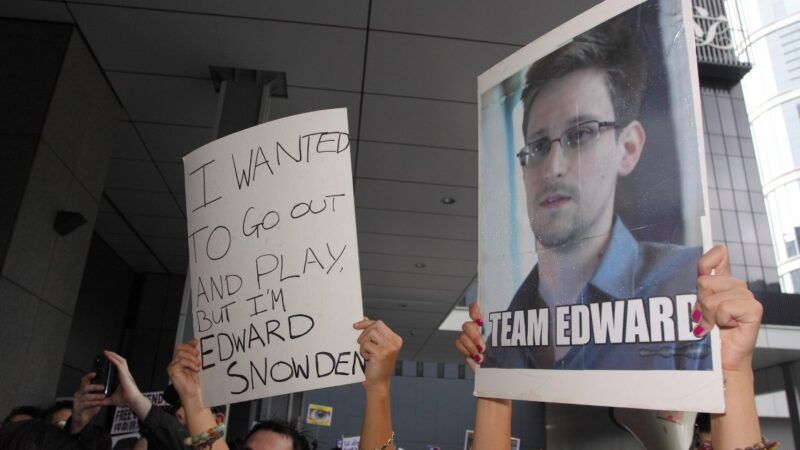

Since 2013, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has been filing motions to get the federal Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) to release secret opinion connected to the collection of Americans' communications data. The first motions began after Edward Snowden's disclosures that the National Security Agency (NSA) was using Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act to scoop up millions of Americans' internet and phone records, without warrants and without the targets' knowledge, allegedly as part of the post-9/11 war on terrorism.

Much of what the FISC, authorized by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, does is classified, because part of its purpose is to permit the covert observation of people who may represent a threat to national security. But another part of the court's purpose is to make sure that Americans are protected from unauthorized secret surveillance. Snowden's disclosures suggested a breakdown in those protections.

The ACLU hoped to uncover the legal justification for this use of the PATRIOT Act. When Section 215 was replaced by the USA Freedom Act in 2015, the group filed a new motion under the new guidelines. And in April of this year, the ACLU, along with the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University and the law firm Gibson Dunn, filed a petition to the Supreme Court asking the justices "to recognize a First Amendment right of public access to the FISC's opinions—ensuring that the opinions are released with only those redactions necessary to prevent genuine harm to national security."

In this morning's orders, the Supreme Court declined to consider the argument. The justices didn't explain why they turned it down, which is typical. But Justice Neil Gorsuch penned a notable dissent that was joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

The federal government has argued that because these reports are so heavily classified, it's the sole province of the executive branch—not the judicial branch—to determine what may be released. Indeed, it has argued that the judicial branch doesn't have any role to play in this process at all (aside from FISC, which has ruled that it doesn't have the authority to consider whether reports should be released). This did not sit well with Gorsuch, who writes:

This case presents questions about the right of public access to Article III judicial proceedings of grave national importance. Maybe even more fundamentally, this case involves a governmental challenge to the power of this Court to review the work of Article III judges in a subordinate court. If these matters are not worthy of our time, what is?

The ACLU and Knight First Amendment Institute put out a joint release expressing disappointment at the court's rejection of the petition.

"The Supreme Court has left in place a system that makes informed public debate about government surveillance exceedingly difficult," writes Alex Abdo, the Knight Institute's litigation director. "Without access to the FISC's opinions, the public cannot evaluate the powers that the government's surveillance agencies are exercising in its name. The FISC shouldn't be exempt from the constitutional right of access that applies to other courts. It's past due for the Court to establish this principle."

In the meantime, we'll have to keep relying on the whistleblowers.