ACLU Thinks the Second Amendment Is a Threat to the First Amendment

"Restrictions on guns in public spaces are appropriate to make public spaces safe for democratic participation."

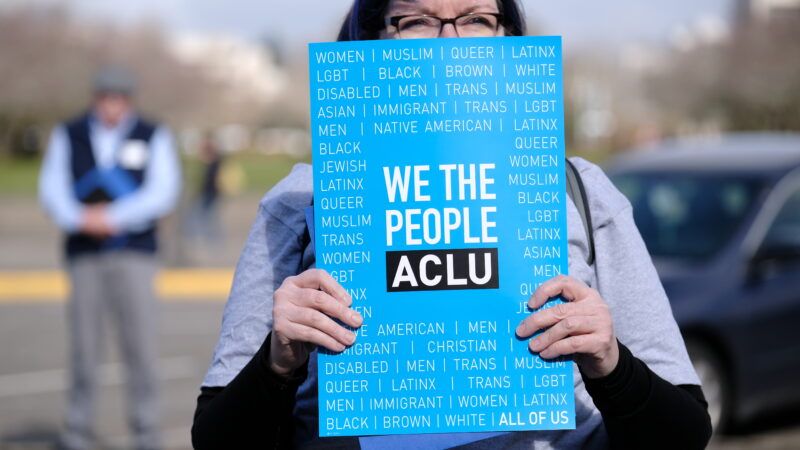

On Tuesday, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and its New York affiliate organization, the NYCLU, jointly announced they had submitted an amicus brief in the upcoming Supreme Court case New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Corlett, which could determine the future of New York's onerous, barely navigable process of concealed carry licensure. Unfortunately, the organization that refers to itself as "our nation's guardian of liberty" is on the side of this illiberal process.

In the press release announcing the brief, the ACLU averred that "restrictions on guns in public spaces are appropriate to make public spaces safe for democratic participation, including First Amendment activity such as assembly, association, and speech." In other words, the ACLU has decided that exercising one's Second Amendment rights may run counter to someone else's First Amendment rights, and is favoring the latter over the former. As evidence, the ACLU cites a case from last summer in which a Black Lives Matter rally in Florida was disrupted when a counter-protester—who also happened to be a concealed-carry license-holder—pulled out a handgun and threatened some marchers.

Regardless of one's permit status, it is already illegal to threateningly brandish a weapon, including in Florida. It remains to be seen how one could not defend both rights equally, even in such a scenario.

The ACLU has been and continues to be a forthright defender of civil liberties in many situations, and a thorn in the side of presidential administrations of both political parties. At the same time, however, its defense of the Second Amendment has been rather lackluster. Even the organization's internal philosophy on the subject is, at best, muddled, ranging from an erstwhile recognition of an individual right while pressing for "reasonable" regulations, to its most recent claim that the Constitution affords "a collective right rather than an individual right." How a "collective" right can be achieved without a lot of people exercising an "individual" right is left unaddressed.

In recent years, the ACLU has evolved on the issue even more distressingly: In 2017, the Virginia ACLU sued on behalf of alt-right activist Jason Kessler when the city of Charlottesville, Virginia, would not allow him to hold his approved rally, dubbed "Unite the Right," in his preferred location. The ACLU won the suit, but the rally infamously devolved into violence, with dozens of injuries and one death. In the aftermath, a portion of the ACLU staff revolted, signing an open letter in which they decried the organization's "rigid stance" on defending the rights of the alt-right and white supremacists.

The following year, the national organization put out an internal memo clarifying its case selection guidelines: Rather than stridently fighting for the right to speech and peaceful assembly even for the most detested people, the organization would now weigh such competing considerations as "the extent to which the speech may assist in advancing the goals of white supremacists or others whose views are contrary to our values" and "whether the speakers seek to carry weapons." While the memo does reaffirm the ACLU's commitment to "continue our longstanding practice of representing [disfavored] groups," former Executive Director Ira Glasser and former board member Wendy Kaminer both questioned whether the language of the memo was simply to give the organization cover to refuse such cases in the future.

If that were the case, it would directly contradict the historical role of the ACLU, which has famously taken on such cases as National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie and Brandenburg v. Ohio, both of which it still touts on its website. In both cases, the ACLU won the right for neo-Nazis to march and chant hateful slogans, in the latter scenario while armed. Brandenburg, specifically, narrowed the rubric of speech that the government could criminalize, a big win for freedom of speech. Yet Kaminer wondered whether, "given its new guidelines," the ACLU would even take up such a case today.

More than a decade has passed since the Supreme Court weighed in on a major Second Amendment case, after affirming an individual right to armed self-defense in 2008's District of Columbia v. Heller and incorporating that right among the states in 2010's McDonald v. Chicago. Those cases, however, were limited to an individual's right to possess firearms in his own home, leaving the prospect of concealed carry for another day.

Concealed carry is a contentious topic in plenty of places around the country, but in New York, it can be especially inscrutable: In order to successfully obtain a license to carry a concealed weapon, applicants must demonstrate that they have a "proper cause" to do so. "Proper cause," of course, is never defined, and judicial decisions have even determined that a "generalized desire to carry a concealed weapon to protect one's person and property" is insufficient to qualify as "proper cause."

In practice, of course, this leads to unequal application of the law, wherein low-income individuals who want weapons for protection are denied, while the wealthy and well-connected are approved. Long before he was under the purview of the Secret Service, former President Donald Trump employed his own private security team, since at least the 1990s. Nonetheless, Trump acknowledged in 2012 that he personally did, in fact, have a New York concealed carry permit.

In the ACLU/NYCLU joint press release, the organizations even concede that "like so many other laws in our country, some gun restrictions were historically enacted and targeted disproportionately against Black people." This is undoubtedly true. And yet, they nonetheless argue that "across-the-board restrictions on open and concealed public carry have long been applied universally to all persons, and are an important means to maintain safety and peace in public spaces and help curb threats of violence against protestors." Therefore, if a legal restriction is applied to everyone, rather than simply people of color, it passes muster.

Interestingly, this puts the ACLU/NYCLU on the opposite side of the issue as a consortium of public defender organizations. Earlier this year they filed a brief of their own in favor of scrapping the New York law, based upon the "hundreds of indigent people" they represent each year, who are prosecuted for keeping handguns for self-defense, "virtually all [of whom]…are Black and Hispanic."

The Supreme Court is expected to hear oral arguments in November. In the meantime, though, it is a shame that the ACLU has continued to take a position contrary to its own explicitly stated goals. When the organization calls itself "the nation's premier defender of the rights enshrined in the U.S. Constitution," it apparently refers to all but one.