Why Does Janet Yellen Suddenly Sound Like Trump on Trade?

In comments to The New York Times Magazine published this week, the new treasury secretary says free trade has been "so negative" for "a large share of the population." That's just wrong.

In June 2018, just a few months after she'd been replaced as chair of the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen issued a stark warning about the populist tendencies emanating from the White House.

"We're seeing a huge retreat from the principles the U.S. has espoused and all the institutions that we built in the postwar period. Resisting protectionism and strongly supporting a rules-based multi-lateral system are what the US stood for and promoted as a global system with great success," reads the transcript of Yellen's remarks from an event hosted by Credit Suisse, an investment bank based in Switzerland. She went on to say that there are "legitimate" trade issues with China that should be addressed, but argued that turning away from the global economic system was "a very worrisome development."

"I believe that system is responsible for great improvements in growth and well-being around the globe," Yellen said.

None of that was unusual for Yellen, who once served as a top economic advisor to the Clinton White House and last month became the first woman confirmed to the post of treasury secretary. Indeed, as recently as last year, during an event at the World Bank, she beamed that "the growth of trade that we have seen over the last 50 years in the development of global supply chains has been one of the most important factors boosting growth all around the world."

It's pretty obvious that Janet Yellen is no protectionist. That's exactly why a more recent comment from Yellen, included as part of a long profile of several top Biden economic advisers and officials published this week by The New York Times Magazine, almost jumps off the page when you read it.

"The trend toward globalization has resulted in losses for workers, and the time has come to really remedy that—the impact has been simply so negative on such a large share of the population," she told the Times' Noam Scheiber.

It's the sort of quote—especially the dramatic and unquantifiable inflation: so negative for such a large share of the population—you might expect from a populist politician with little interest in economic reality, like former President Donald Trump or Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.). Coming from the measured, academic mind of Yellen, it seems wildly out of character.

The best explanation, of course, is that Yellen is just trying to be a team player here. The Biden administration has signaled that it is unwilling to make a sharp break with Trump's trade policies, likely because the White House sees domestic political benefits of talking about protectionism. Biden's first major trade policy moves were the announcement of a "Buy American" plan for federal procurement that will force taxpayers to pay higher prices for goods the government buys, and the reimposition of tariffs on aluminum imported from the United Arab Emirates. Neither of those things should be expected to do much to boost American manufacturing, but both will marginally increase costs and complicate some of those global supply chains that Yellen knows are key to ongoing economic growth.

But even if she's merely going along to get along, Yellen's sudden transformation from a defender of globalization to a cheerleader for protectionism is, as she might have once described it, "a very worrisome development." That her boss, the president, has undergone an apparently similar change of heart—Biden once championed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and served as the Obama administration's top advocate for the doomed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)—is also not great.

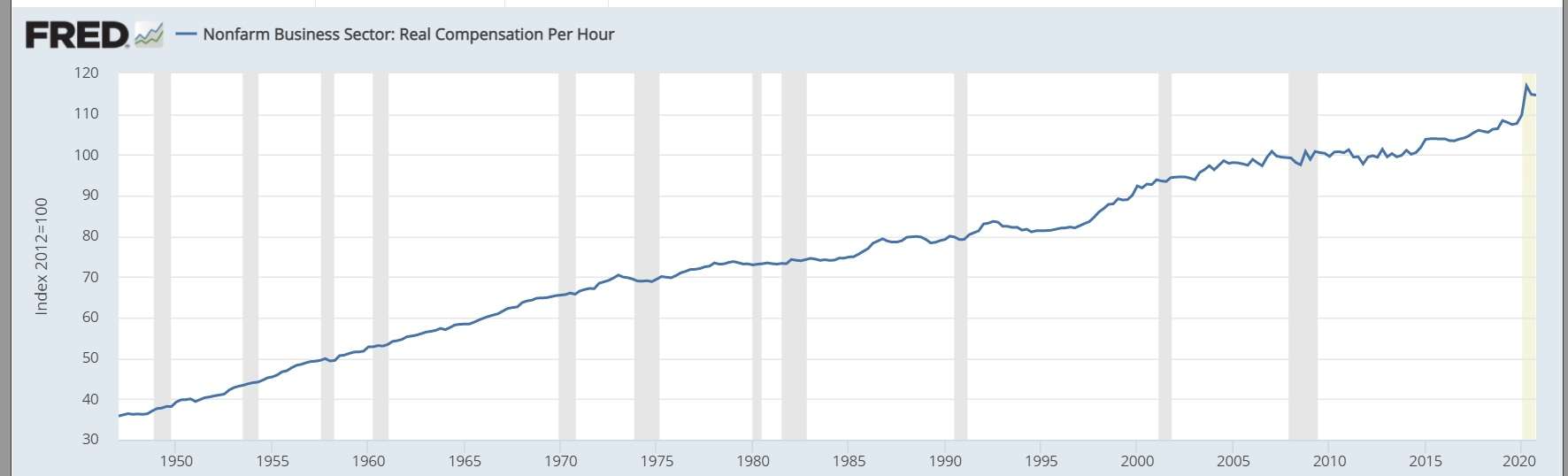

Protectionism is so hot right now, but that doesn't mean it's the right course. Yellen, of course, knows this. The idea that a global system of trade has been "so negative" for such a "large share of the population" is simply not borne out by the data. Probably the most direct way to disprove this claim is to look at the average hourly earnings of American workers over the past 70 years.

To put it simply, this is not what you'd expect to see if a "large share of the population" was suffering.

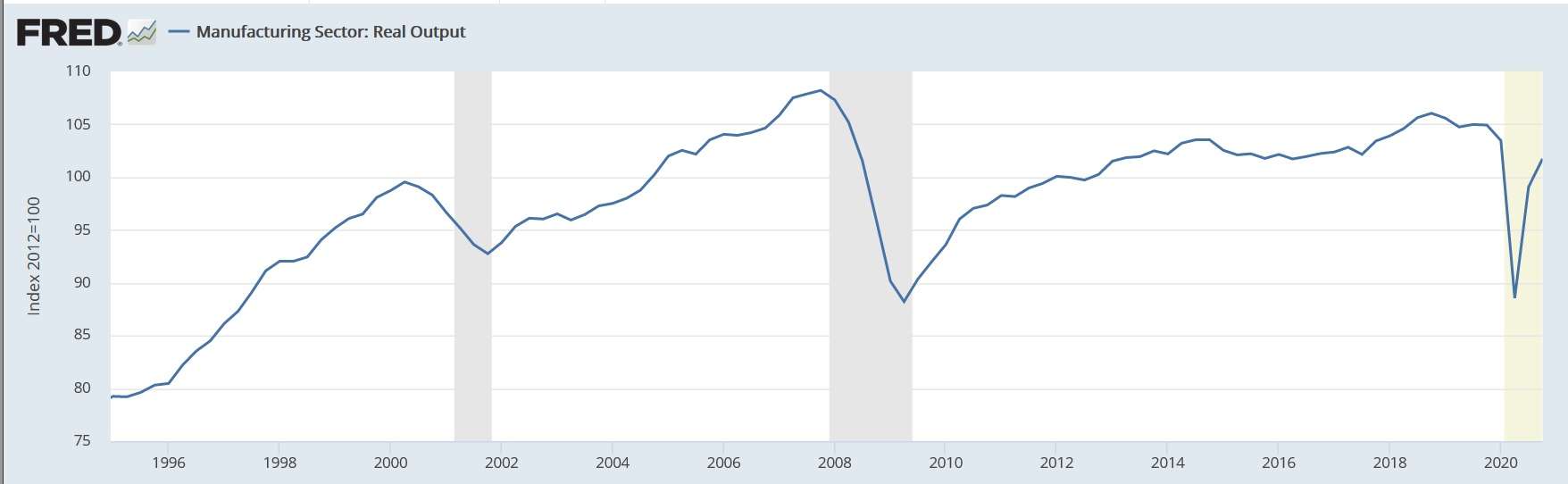

When you strip away the exaggerated rhetoric, what the protectionists that have taken over both major parties are really concerned about is the decline in manufacturing jobs in America. The number of Americans employed in manufacturing has fallen from 17 million to about 12 million in the past 20 years—this is hardly a national crisis that requires overturning the entire global economic system. There are certainly some people for whom that decline has been painful, but Yellen (and Biden and everyone else who is serious about federal policy making) should understand the difference between data and anecdotes.

Furthermore, the decline of manufacturing as a share of the whole American economy has been more or less on a steady downward march since the end of World War II. This isn't a crisis created by the rise of China or the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. It's a function of macroeconomic elements far beyond the poor power of any presidential administration to control or reverse.

Fewer workers are employed in manufacturing, but the average worker is earning far more per hour. This is a problem? Meanwhile, American manufacturing output is significantly higher today than it was when the WTO was established. In fact, even at the lowest point of last year's COVID-19 recession, manufacturing output was still higher than it had been in any year before 1997.

Investment in American manufacturing—from both domestic and foreign sources—has grown steadily in the past two decades, as Scott Lincicome, senior fellow in economic studies at the Cato Institute, pointed out in a report published last month.

"If you look at what actually happened from 1994 to now, which encompasses the creation of NAFTA and the WTO and China joining the WTO, real median weekly earnings for U.S. workers increased by nearly 20 percent while we added about 30 million new jobs," says Bryan Riley, director of the free trade initiative at the National Taxpayers Union Foundation, a free market think tank. "So, obviously, the vast majority of U.S. workers are much better off now than they would be if we turned back the clock to 1993 or earlier, and a lot of that progress is due to international trade and investment."

But these data points probably miss the biggest benefit that American workers have gained from globalization: access to goods they otherwise wouldn't have been able to afford—everything from smartphones to pandemic-ending vaccines are the product of global supply chains.

In short, there is no crisis of American manufacturing. And there is certainly no evidence that the globalization of manufacturing jobs has been "so negative" for a "large" share of American workers. Where there are economic issues created by the displacement of jobs, there might be an argument (though probably not a very convincing one) for government aid to those who have been harmed. That's a far cry from the positions that both major political parties are increasingly taking.

Or, as Yellen herself put it just a few years ago, global trade "is responsible for great improvements in growth and well-being around the globe."

If the new administration is going to fulfill its promise to return America to something resembling normalcy, Biden and Yellen should not let the misguided protectionists control this debate.