'We Can Fact Check Your Ass,' but Not When It Comes to Political Ads

Twitter has made a bad decision when it comes to banning political ads from its site. They should trust users to decide what is right or wrong.

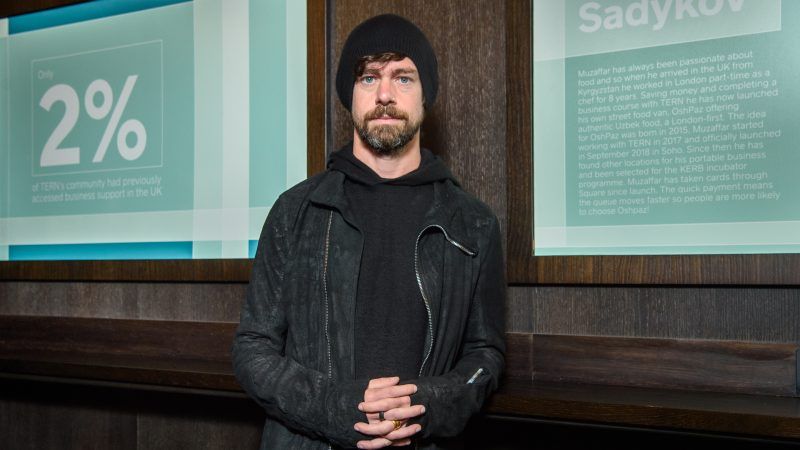

On the heels of Facebook announcing it would allow misleading or even factually-incorrect political advertisements, Twitter has announced that it will forego running all paid ads for individual candidates and issues. As Reason's Scott Shackford notes, Twitter has not yet released its final guidelines (Twitter head Jack Dorsey has promised to deliver them by November 15) and both platforms are clearly responding to threats by legislators seeking to regulate social media.

The differing approaches to the issue of paid speech provide a good opportunity to discuss not just how political communications work in a post-broadcast world but also how the internet is falling short of its promise to radically alter the way people communicate and connect. There are many reasons to criticize Twitter's decision (which, as a private platform, it has every right to make), but the ultimate reason is this: It represents a near-complete lack of faith in users to function as critical consumers of information.

In a long thread, Dorsey extols the virtue of organic "reach" on Twitter, writing:

A political message earns reach when people decide to follow an account or retweet. Paying for reach removes that decision, forcing highly optimized and targeted political messages on people. We believe this decision should not be compromised by money.

He immediately recognizes that the very same argument can be made against all forms of advertising, which is how Twitter makes money, so he feels a need to claim that political speech is uniquely serious:

While internet advertising is incredibly powerful and very effective for commercial advertisers, that power brings significant risks to politics, where it can be used to influence votes to affect the lives of millions.

Internet political ads present entirely new challenges to civic discourse: machine learning-based optimization of messaging and micro-targeting, unchecked misleading information, and deep fakes. All at increasing velocity, sophistication, and overwhelming scale.

This sort of thinking represents a fundamental betrayal of the ideals that helped build the internet into an unparalleled, open system of knowledge and information. Dorsey is effectively saying that we—you, me, and the typical Twitter user—can't manage to sift wheat from chaff online.

Go back to the mid-1990s, as the World Wide Web was becoming a mass medium, and you'll find everyone talking excitedly about "disintermediation," or the removal of middlemen and gatekeepers from all sorts of cultural, economic, and political transactions. Finally, we would all be able to find and connect directly with like-minded souls in hyper-personalized, ultra-niche communities and markets (this spirit is alive and well in the bitcoin/blockchain space, with boosters celebrating the end of the need for "trusted third parties" to issue currency and validate transactions). Transactions would become more direct—and thus cheaper and more efficient. That attitude fit hand-in-glove with a belief that people could generally be trusted to act honestly and forthrightly, either because they were freed of the corrupting influence of intermediary institutions or because of forced transparency.

"We can fact check your ass," crowed pioneering online journalist Ken Layne in the early 2000s, announcing an ostensibly brave new world in which untruths, half-truths, and patently false claims would be readily debunked by legions of readers and writers who now had access to the means of publication. What was true for journalism was true for everything else, too: The reputations of once-sanctified professionals such as doctors, lawyers, and even college professors (remember Rate My Professors?) suddenly became matters of public record rather than recommendations passed along in semi-secrecy to the advantaged few. For the first time, car dealers had to face customers who had something approaching equal information about automobile costs (look upon Edmunds.com and despair, old school salesmen!). Online merchants were subjected to publicly accessible reviews. Piping up about the food and service at restaurants quickly became the province of amateur critics. Anti-tax activist Grover Norquist pushed to put all government transactions online on the theory that somebody somewhere would be interested in sifting through checks and bringing meaningful information to light (that spirit is alive and well in groups such as Open the Books).

There were, of course, more than a few complications. It turns out that middlemen often provide massive value for customers by sifting through a lot of information, data, or choices and presenting a few items in a given field. It's a good thing that the power once held by, say, record labels has faded, but there's no question that the A&R guys at Columbia or Atlantic listened to a lot of bad music so the rest of us didn't have to. The same is true of publishing houses, clothing stores, and a lot of institutions and structures that literally and figuratively brought things to market. If you ever deputized a friend to pick movies or restaurants or clothing for you, you understand the value of middlemen or guides or editors. In 1994, former Reason Editor Virginia Postrel argued persuasively that as more raw information, news, and data became available we'd enter the "age of the editor" precisely because we would need trusted people who could help us navigate all the choices in front of us.

But the biggest complication to the simple idea that the internet and disintermediation would bring us the whole truth and nothing but the truth is simply this: We have different definitions of what is true, what is good, and what is meaningful. This is especially the case in politics, which is a lot more like religion than math. Most religions claim some monopoly on "truth," but what they're really providing is a way of seeing and understanding the world in ways that are subjective. Same with politics. Is Donald Trump's vision of what is wrong with America and how to fix it true or is Bernie Sanders'? I'd say neither is. But what the internet does (especially platforms like Facebook and Twitter) is enable more of us to directly enter the discussion—the argument over who is right and who is wrong. That's a great and liberating development but one that is mostly ignored by Twitter's Dorsey, who instead focuses on the creator of content rather than the consumers of it:

We need more forward-looking political ad regulation (very difficult to do). Ad transparency requirements are progress, but not enough. The internet provides entirely new capabilities, and regulators need to think past the present day to ensure a level playing field.

As a matter of history, it should send a chill down everyone's spine when anyone talks about regulating political speech. Campaign finance laws, including innocuous-sounding transparency requirements, are routinely used to penalize outliers such as the Socialist Workers Party. More than that, "the entirely new capabilities" provided by social media include the ability to engage, critique, and research any and all claims that come our way. We can indeed fact-check the ass of every advertiser we stumble across. Even more radically, we can block them at the click of button. If Dorsey wants to improve political discourse in cyberspace, he would do far better to give users more tools to tailor their experience as they see fit than to start banning whole categories of ads (which will be much harder in practice than theory; will Twitter ban paid endorsements by popular users as unfair? What about unpaid ones?).

"At some point," writes Jeff Jarvis, an early theorist of the ways in which online culture was empowering individuals in powerful new ways. "We must trust the public, the electorate, ourselves. If we cannot, then we are surrendering democracy. We must put our faith in the public conversation." Jarvis is a critic of both Twitter's and Facebook's political ad policies for reasons that are different from mine. But what is great and unique about the internet and social media is precisely that it allows more of us to participate in ever-changing and always-contested definitions of what is good, true, and relevant. Yes, yes, Twitter and Facebook and all the other platforms have every right to make whatever decisions they want, but when those choices are at odds with the internet's essential spirit, they deserve to be criticized.