Does Legalizing Marijuana Cause 'Sharp Increases in Murders and Aggravated Assaults'?

The link that Alex Berenson perceives between cannabis and violence is not apparent in careful research on the issue.

Alex Berenson, the former New York Times reporter who has just published an anti-pot polemic that he aptly named after a notoriously hysterical 1936 anti-pot movie, says marijuana legalization "appears to lead to an increase in violent crime." Like his claim that marijuana causes schizophrenia and other "serious mental illnesses," his claim that it causes violence is based on a highly selective reading of the evidence.

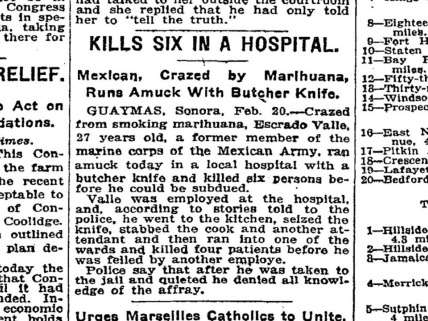

"The first four states to legalize—Alaska, Colorado, Oregon and Washington—have seen sharp increases in murders and aggravated assaults since 2014, according to reports from the Federal Bureau of Investigation," Berenson writes in the Times. "Police reports and news articles show a clear link to cannabis in many cases."

As Jesse Singal notes, selecting 2014 as the starting year seems suspect, since two of those states (Colorado and Washington) approved legalization in 2012. But 2014 does coincide with the lowest national violent crime rate since the late 1960s. The national rate rose by 3.5 percent in 2015 and by 3.4 percent 2016, then fell by about 1 percent in 2017, for a total increase of about 6 percent between 2014 and 2017. It's true that the increase in violent crime was sharper in the four states that Berenson mentions. Can the difference be attributed to marijuana legalization?

Probably not. University of Oregon economist Benjamin Hansen finds that "the homicide rates in Colorado and Washington were actually below what the data predicted they would have been given the trends in homicides from 2000-2012." He says "we can't conclude that marijuana legalization increases violence, and perhaps even there could be small negative effects."

Nor is the effect that Berenson perceives apparent in national data. The share of Americans reporting past-month marijuana use in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health rose by 55 percent from 2002 to 2017, a period when the national violent crime rate fell by 23 percent.

How plausible is it that legalizing marijuana would immediately cause "sharp increases in murders and aggravated assaults"? Here is how a bunch of experts at the RAND Drug Policy Research Center summarized the evidence in a 2013 report commissioned by the Office of National Drug Control Policy: "Even though marijuana is commonly used by individuals arrested for crimes, there is little support for a contemporaneous, causal relationship between its use and either violent or property crime. There is evidence supporting a possible intertemporal relationship, but it is not clear to what extent this is unique to marijuana." The authors flatly state that "marijuana use does not induce violent crime," while "the links between marijuana use and property crime are thin."

In line with that research, several studies have found that relaxing legal restrictions on marijuana is not associated with an increase in violent crime. A 2016 analysis of data from 11 Western states, published in the Journal of Drug Issues, found "no evidence of negative spillover effects from medical marijuana laws (MMLs) on violent or property crime." To the contrary, the researchers found "significant drops in rates of violent crime associated with state MMLs."

A 2017 study published in Contemporary Drug Problems compared FBI crime data in states with different legal regimes and found that "property and violent crime rates appear to be lower in both decriminalized and medically legalized states, but the difference is not statistically significant." A 2018 study published by Germany's Institute of Labor Economics compared California counties with different policies regarding medical marijuana dispensaries and found "no relationship between county laws that legally permit dispensaries and reported violent crime." Another 2018 study, published in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, found "no causal effects of medical marijuana laws on violent or property crime at the national level" and "no strong effects within individual states, except for in California, where the medical marijuana law reduced both violent and property crime by 20%."

If letting people use marijuana for recreational purposes leads to "sharp increases in murders and aggravated assaults," you would expect to see something similar in jurisdictions that allow medical use, especially when the rules are loose, as they were in California for two decades before full legalization. Yet these studies find nothing of the sort. And if more marijuana use means more "paranoia and psychosis," resulting in "an increase in violent crime," as Berenson claims, you would expect that the national increase in cannabis consumption would have been accompanied by a national increase in violent crime. Yet exactly the opposite happened.

Berenson's book has received respectful reviews in The New Yorker and Mother Jones, along with considerable pushback from people who study these issues. You can expect to see more of the latter.