'Institutionalized Fear' Tarnishes Boston Marathon

Security measures don't make us safer, but they're apparently here to stay

Once again in the wake of the bloody 2013 bombing, the Boston Marathon is subject to heightened security—or the appearance of security, anyway. Attendees are discouraged from bringing backpacks and strollers and are subject to random bag checks, thousands of police and National Guard troops patrol the route and man checkpoints, private drones are banned, and people will enjoy the day under the watchful lenses of hundreds of surveillance cameras. "We also ask the public for vigilance," says Boston's Mayor Martin J. Walsh, "and are encouraging everyone, if you see something, say something.

OK, we get it. Eyes are everywhere, and so are uniforms. But is this living memorial to the old East Germany likely to make anybody safer?

"I don't think there's a lot of safety to be gained," security expert Bruce Schneier told me when similar measures were implemented for last year's Boston Marathon. "It's really for a show of force" rather than to prevent a recurrence of something like 2013's terrorist attack.

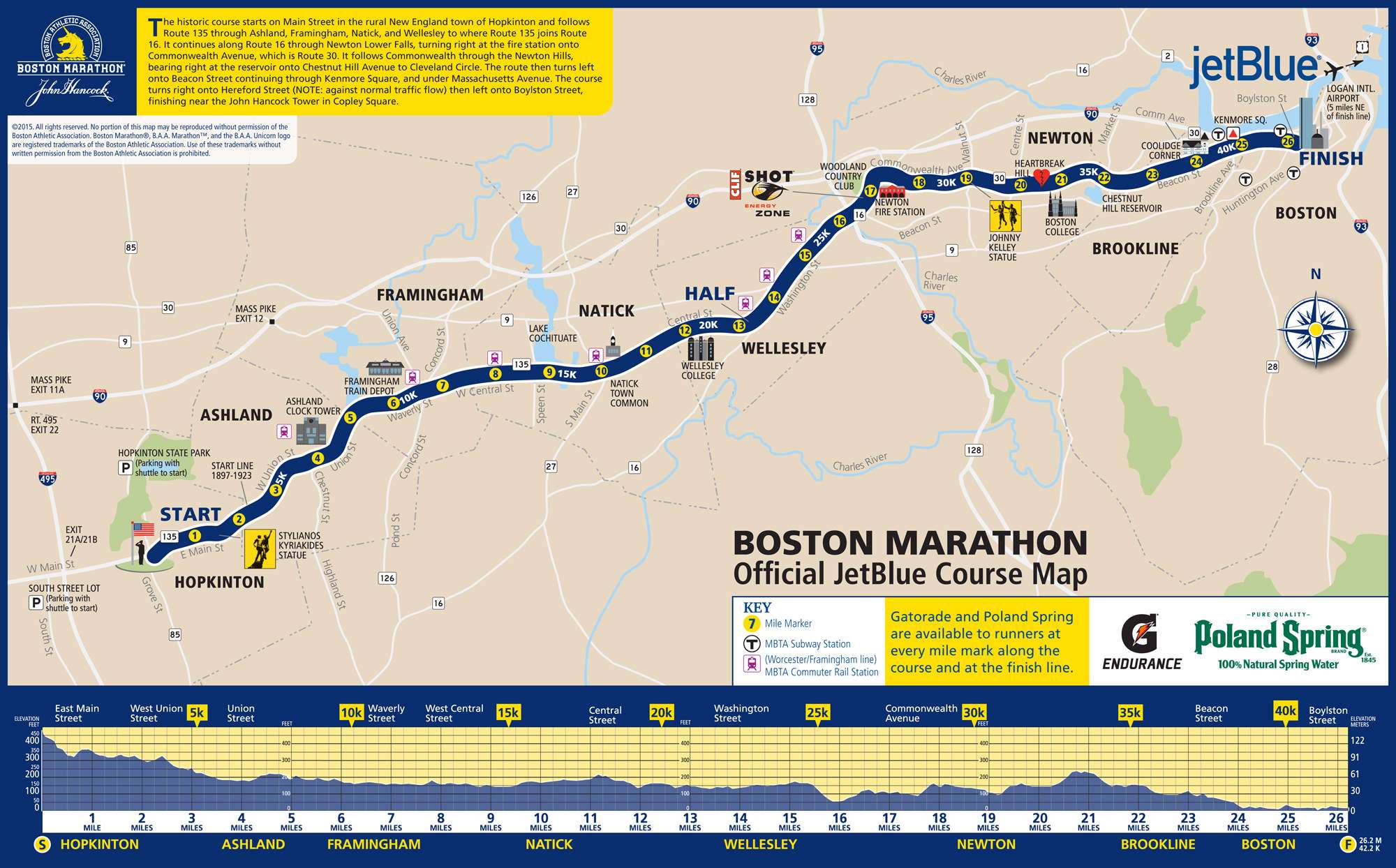

Given the 26 miles of open road involved, he didn't see how cops and Guardsman pawing through random backpacks would do anything to deter an attacker. They'd be left to respond to another incident after the fact.

The 2013 attack was lethal and horrible. It was also a (happily) rare incident. In 2013, the most recent year for which the U.S. State Department publishes data, 16 Americans were killed overseas in terrorist incidents. That's up from the 10 killed in 2012, but down from the 17 deaths in 2011. Even the roughly 3,000 people murdered by the 9/11 attacks were a small fraction of the over 42,000 killed in car accidents (PDF) that year. That's not much reassurance if you're one of the victims or if you knew them, but it adds some important perspective when considering those checkpoints, cops, and random searches.

The security presence "has institutionalized fear," Schneier warned last year. "It reinforces the notion that terrorism is a big deal, when in fact…it's a really minor risk."

Nothing has changed since then. The minimal risk hasn't grown. Nor have the security efforts become more likely to actually make anybody safer. But the cops and troops and intrusions are back for another year.

"Police may implement what is billed as a temporary security regime, but then turns out to be permanent," Kade Crockford of the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts told me for that 2014 piece. "All too often, when law enforcement beef up security for special events like political conventions or major sports competitions, the surveillance apparatus that's established remains firmly in place long after the crowds are gone."

Last week, Matt Welch wrote of the pointless security gauntlet baseball fans now have to navigate to get into a ballpark. You can enjoy a pat-down at football games, too.

The surveillance apparatus may or may not be here long after the crowds are gone, but it's become a regular feature of any sort of public event. And we gain nothing by its presence.