Drinking Yourself to Death Is Not Quite As Easy As the CDC Implies

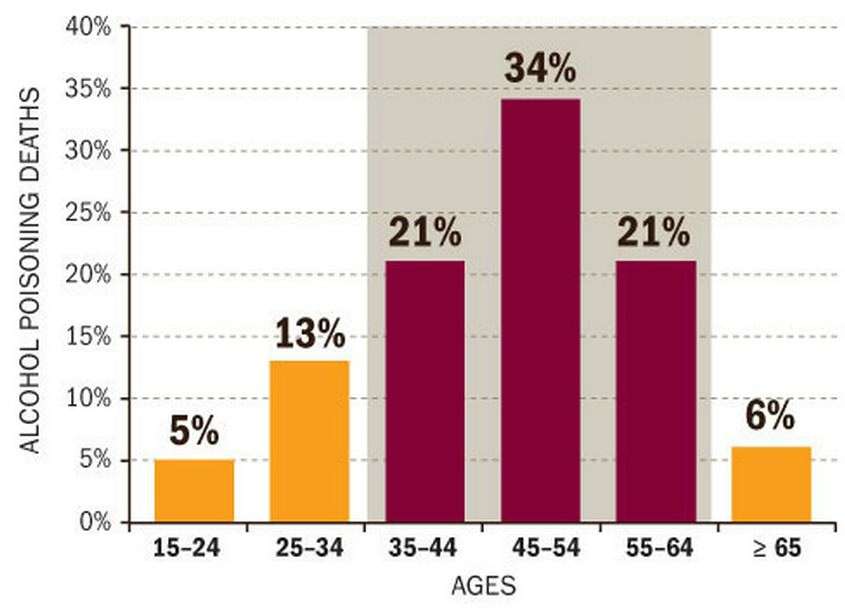

In a report published yesterday, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says alcohol poisoning killed an average of 2,221 people a year in the United States from 2010 through 2012. That's six people a day, which may not seem like much compared to smoking-related disease, which according to the CDC kills 1,315 people a day in the U.S., or even car accidents, which according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration kill 92 people a day (mostly in crashes that are not alcohol-related). But six fatalities a day is a lot compared to the death toll from, say, marijuana overdoses, which is zero. Nor is that the only way in which alcohol is more dangerous than marijuana. Acute poisoning accounts for less than 3 percent of the 88,000 or so annual deaths attributed to alcohol, while the most precise estimate of the death toll from marijuana is "more than zero."

This context helps put into perspective concerns about the consequences of marijuana legalization. In a report issued this week, the anti-pot group Project SAM says "there have been at least 2 deaths related to marijuana edibles in 2014." These are the only deaths attributed to marijuana that prohibitionists have been able to identify since Colorado legalized the drug at the end of 2012. One death was a murder, while the other was a fatal fall from a hotel balcony, and in both cases marijuana's causal role is debatable. During this same period, how many people died of alcohol-related causes in Colorado? Judging from the CDC's state-level data, around 150 Coloradans died just from acute alcohol poisoning—which, again, accounts for a small percentage of alcohol-related deaths. Data from 2006 through 2010 indicate that Colorado's two-year total would exceed 3,000. It's useful to be reminded that drinking yourself to death is relatively easy, while killing yourself with pot is pretty damned hard.

As usual, however, the CDC exaggerates the hazards of drinking by conflating common patterns of alcohol consumption with deadly recklessness. It warns that "binge drinking can lead to death from alcohol poisoning." That observation would be unobjectionable were it not for the CDC's idiosyncratic definition of "binge drinking," which it equates with consuming five drinks "on an occasion" for men; the cutoff for women is four drinks. That level of consumption, the CDC notes, "typically leads to a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) that exceeds 0.08 g/dL, the legal limit for driving in all states." In fact, that was the rationale for choosing these cutoffs, which are based on how alcohol affects driving ability, as opposed to how it affects the drinker's health.

According to the CDC, you should never be too drunk to drive, even if you have no intention of doing so. It implies that drinking that much endangers your health regardless of your transportation plans. Hence the absurd suggestion that someone with a BAC of 0.08 percent is on the verge of dying from alcohol poisoning, when in fact he would have to drink five to six times as much to enter that danger zone.

"The more you drink," the CDC warns, "the greater your risk of death." As a general proposition, that is simply not true: The relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality follows a J-shaped curve, meaning that drinking more is associated with better health—up to a point. According to a 2006 analysis of 34 prospective studies published in the Archives of Internal Medicine, mortality rates start to rise for men when they exceed an average daily consumption level of four drinks. That is probably a conservative estimate, since people tend to underreport their drinking, but it is still much more generous than the CDC's recommendation. The CDC says men should consume no more than 14 drinks a week, or an average of two a day. According to the CDC, less is always healthier—even when it isn't.