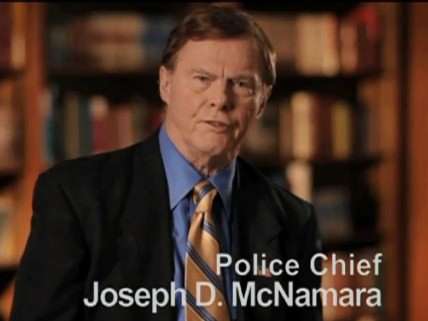

Joseph McNamara, Drug Warrior Turned Conscientious Objector, RIP

Joseph McNamara, who died on Friday at the age of 79, had been publicly criticizing the war on drugs since retiring from his last job in law enforcement, running the San Jose Police Department, more than two decades ago. When he began his second career as a drug-war dissident in 1991, Americans were overwhelmingly opposed to legalizing even marijuana, so it took guts for him to argue that violence is not an appropriate response to drug use, especially given his professional background. That background made McNamara an especially effective critic of prohibition, since he had witnessed its futility and pernicious consequences firsthand.

In a 2002 interview with Reason's Michael Lynch, McNamara explained that he had harbored doubts about the vain crusade to stop Americans from using certain arbitrarily chosen psychoactive substances since his days as a New York City beat cop in the 1950s. Those doubts solidified when he wrote the thesis for a Ph.D. in public administration from Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government. "I wrote my dissertation in 1973 and predicted the escalation and failure of the drug war—and the vast corruption and violence that would follow," McNamara told Lynch. "I never published it because I wanted a police career and not an academic career." But after he retired in 1991 and became a fellow at the Hoover Institution, McNamara was increasingly outspoken on drug policy, serving as an adviser and speaker for Law Enforcement Against Prohibition and bringing a much-needed insider's perspective to discussions of prohibition's impact on policing.

McNamara was especially incisive in explaining the relatively subtle ways in which prohibition corrupts police practices, as in this excerpt from the Reason interview:

Last year, state and local police made somewhere around 1.4 million drug arrests. Almost none of those arrests had search warrants. Sometimes the guy says, "Sure, officer, go ahead and open the trunk of my car. I have a kilo of cocaine back there but I don't want you to think I don't cooperate with the local police." Or the suspect conveniently leaves the dope on the desk or throws it at the feet of the police officer as he approaches. But often nothing like that happens.

The fact is that sometimes the officer reaches inside the suspect's pocket for the drugs and testifies that the suspect "dropped" it as the officer approached. It's so common that it's called "dropsy testimony." The lying is called "white perjury." Otherwise honest cops think it's legitimate to commit these illegal searches and to perjure themselves because they are fighting an evil. In New York it's called "testilying," and in Los Angeles it's called joining the "Liar's Club." It has lead some people to say LAPD stands for Los Angeles Perjury Department. It has undermined one of the most precious cornerstones of the whole criminal justice process: the integrity of the police officer on the witness stand.

McNamara was talking about the militarization of policing long before it became a subject of much discussion following the recent unrest in Ferguson, Missouri. "When you're telling cops that they're soldiers in a Drug War," he said at the International Conference on Drug Policy Reform in 1995, "you're destroying the whole concept of the citizen peace officer, a peace officer whose fundamental duty is to protect life and be a community servant." He elaborated on the theme in a 2006 Wall Street Journal essay:

Simply put, the police culture in our country has changed. An emphasis on "officer safety" and paramilitary training pervades today's policing, in contrast to the older culture, which held that cops didn't shoot until they were about to be shot or stabbed. Police in large cities formerly carried revolvers holding six .38-caliber rounds. Nowadays, police carry semi-automatic pistols with 16 high-caliber rounds, shotguns and military assault rifles, weapons once relegated to SWAT teams facing extraordinary circumstances. Concern about such firepower in densely populated areas hitting innocent citizens has given way to an attitude that the police are fighting a war against drugs and crime and must be heavily armed.

McNamara also highlighted the racist origins and racially disproportionate impact of drug prohibition, a theme that would later be taken up by critics across the political spectrum, including Michelle Alexander and Rand Paul. "The drug war is an assault on the African-American community," McNamara told Lynch in 2002. "The laws that we have are the last vestiges of Jim Crow."

For years McNamara, who was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer last year, was working on a book titled Gangster Cops: The Hidden Cost of America's War on Drugs. Given the insights he must have gleaned from 35 years as a cop and two decades as a scholar, I was eager to read it. It would have been a fitting coda to his brave work as drug-war veteran turned conscientious objector.