The Tiny Numbers Behind the 'Heroin Epidemic'

The other day I noted that, despite the talk of "soaring" and "skyrocketing" heroin use in the wake of Philip Seymour Hoffman's death, the percentage of the population consuming the drug remains very low. In 2012, the most recent year for which data are available from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 0.3 percent of respondents reported that they had used heroin in the previous year, up from 0.2 percent in 2011. One commonly heard explanation for the increase is that a crackdown on nonmedical use of prescription painkillers made them more expensive and harder to get, driving users of drugs like OxyContin to heroin. Here is how NPR puts it in a story that aired yesterday:

When you talk to people who use heroin today, almost all of them will tell you that their opioid addiction began with exposure to painkillers, says Dr. Andrew Kolodny, chief medical officer for the Phoenix House Foundation and president of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing.

"The main reason they switched to heroin is because heroin is either easier to access or less expensive than buying painkillers on the black market," he says….

As patients became addicted, doctors began cutting back their prescriptions, drug companies agreed to make the pills less snortable, and states created registries of patients who doctor-shopped for prescriptions.

Experts say that's when heroin suppliers stepped in to fill the void.

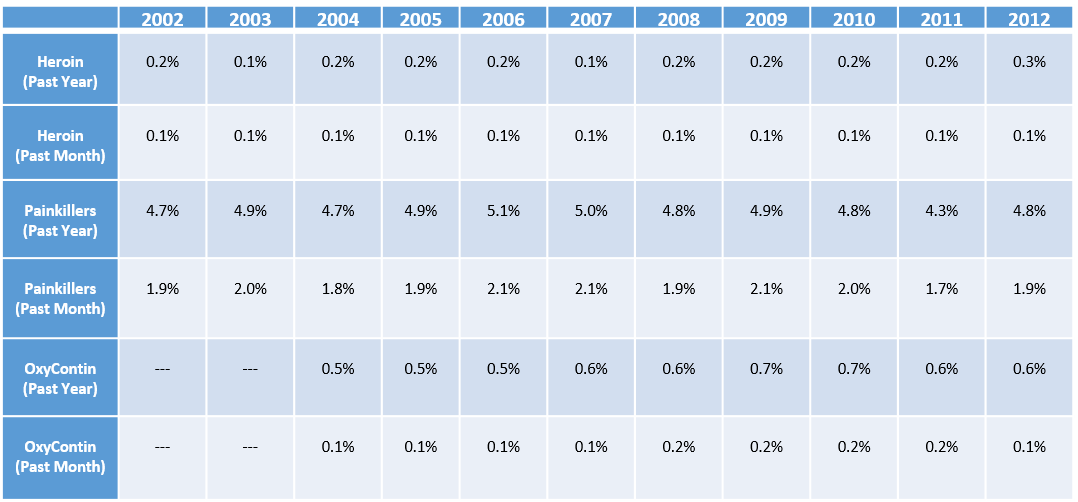

The NSDUH data (below) provide some support for that theory. Between 2011 and 2012, the share of respondents reporting past-month use of OxyContin fell by 50 percent, while the share reporting past-year use of heroin rose by 50 percent. Then again, the rate for past-year use of OxyContin remained steady (as did the rate for past-month use of heroin), while past-year and past-month use of all prescription opioids rose. The last time past-year heroin use rose—between 2007 and 2008, when it doubled from 0.1 percent to 0.2 percent—painkiller use did fall, but past-month OxyContin use rose, while past-year OxyContin use remained steady.

If you look at raw numbers, the evidence seems similarly mixed. The number of past-month heroin users rose from 281,000 to 335,000 between 2011 and 2012, while the number of past-month OxyContin users fell from 434,000 to 358,000, which is consistent with the hypothesis that some people switched from OxyContin to heroin. Between 2007 and 2008, however, the number of past-month heroin users rose from 153,000 to 213,000, while the number of past-month OxyContin users also rose, from 369,000 to 435,000.

Assuming that heroin is substituting for opioids like OxyContin, that is probably not a desirable development, since a black-market product is much less predictable and therefore more dangerous than a legal, pharmaceutical-quality drug. Yet Kolodny, the addiction specialist who says increased restrictions on painkillers are driving up heroin use, argues that the solution is…more restrictions on painkillers. That's a bad idea not just because of potentially harmful substitution effects but also because attempts to prevent nonmedical users from obtaining opioids inevitably hurt patients who need the drugs to relieve pain.

Notice, by the way, that past-month heroin use—a necessary but not sufficient requirement for addiction—has held steady at 0.1 percent for a decade. The raw numbers have increased (from 166,000 in 2002 to 335,000 in 2012), but not enough to kick the rate up a tenth of a percentage point. That fact helps put into perspective the numbers behind what NPR describes as a "heroin epidemic."

Addendum: Kolodny contacted me to clarify that he wants to prevent new cases of addiction by encouraging more-careful prescribing practices and putting hydrocodone combination products such as Vicodin in a more restrictive category (Schedule II rather than Schedule III), while simultaneously increasing access to treatment for current addicts.

[Thanks to Robert Woolley for the NPR link.]