2013: The Year Defiance of the State Became Cool

The year saw many Americans rally behind rebels, explicitly siding with them over the government, in opposition to the powers-that-be.

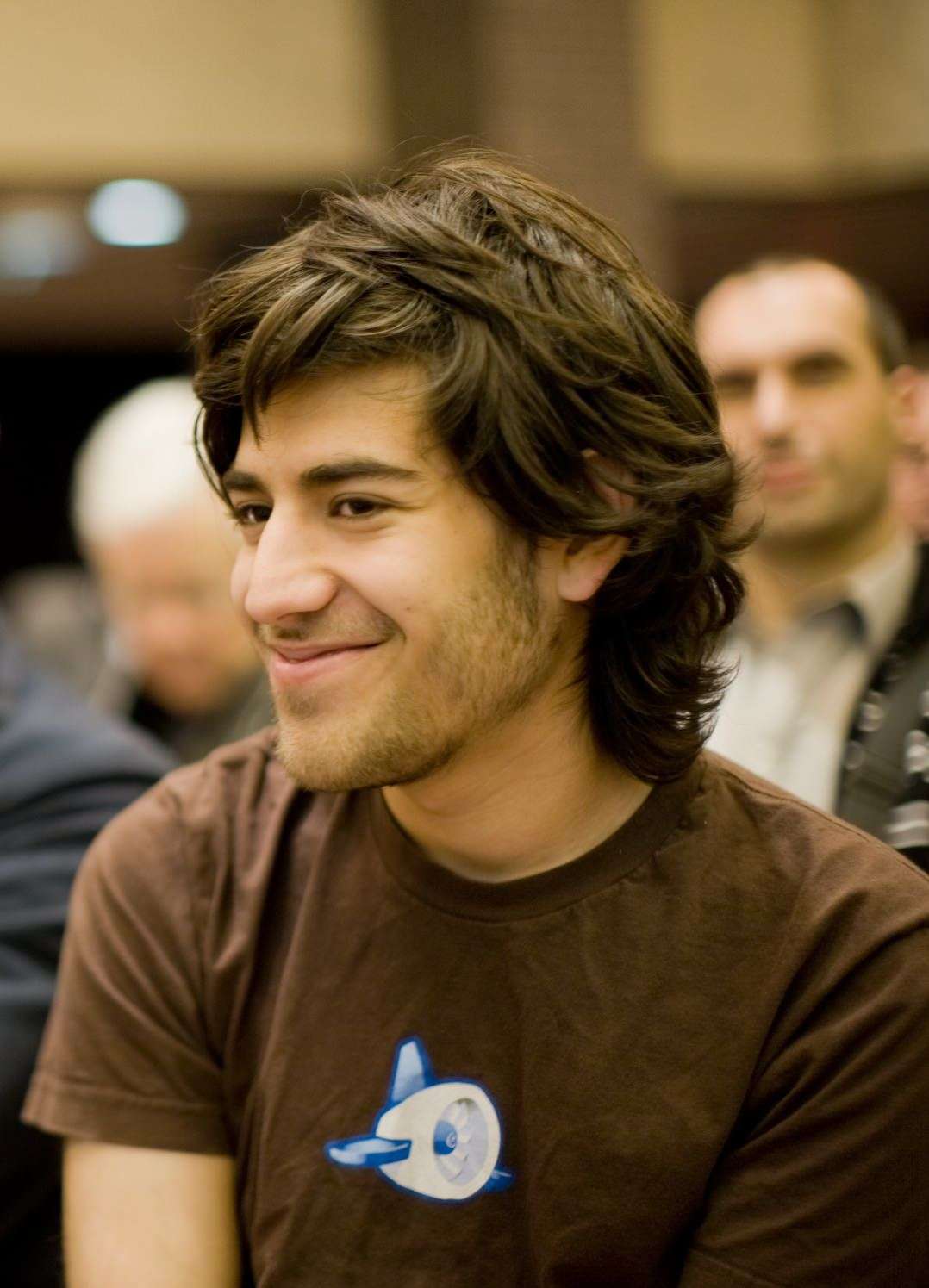

For some high-profile people who publicly told the government to go to hell, 2013 was, personally, a bit rough. Information freedom activist Aaron Swartz took his own life under threat of a brutal prison sentence. Revealer of inconvenient government secrets Bradley/Chelsea Manning actually ended up in prison. And surveillance whistleblower Edward Snowden went into exile in Russia to escape what promised to be a "fair" trial followed by a first-class hanging. But tough consequences aren't unusual for people who defy the state. What was different and encouraging was how many people rallied behind Swartz, Manning, Snowden, and other rebels, explicitly siding with them over the government, in opposition to the powers-that-be.

Swartz's case was supposed to be a warning to us all, after he violated the terms of service of the JSTOR archive by downloading academic papers in bulk instead of one at a time, the better to make them available far and wide. What should have been a civil matter between him and the archive became federal felony charges, with United States Attorney Carmen M. Ortiz threatening "up to 35 years in prison … and a fine of up to $1 million."

This was all "pour encourager les autres," as an ambitious prosecutor sought to demonstrate how tough she could be on the high crime of intellectual property violations.

But after his death, Swartz, already known as a principled activist for making information accessible, quickly became a cause celebre. The case was immediately held up as an example of prosecutorial overreach, even inspiring the introduction of a law to rein-in such legal abuses. Swartz was posthumously inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame. Americans didn't just support the activist; they despised his persecutors—people started talking about the end of Ortiz's political career.

Which is to say, Aaron Swartz, who started the year as a deliberate defier of the law, under criminal indictment, was immediately elevated by many people to the status of the good guy in the conflict. Government officials could either join the bandwagon or sputter in outrage that they were considered villains by their constituents.

Chelsea Manning's case followed a similar, if less lethal, trajectory. Imprisoned by the United States government for leaking a treasure trove of sensitive and often embarrassing documents to WikiLeaks, the story quickly became one about government transparency, mistreatment of prisoners, and the lengths to which officials would go to target its critics.

Manning quickly disclaimed any association with pacifism, saying she acted for the sake of transparency. That was a credible argument, given her connection with WikiLeaks, and one that rang a bell at a time when the U.S. government is seen as both dangerously intrusive into people's lives, as well as excessively secretive about public officials' behavior. (President Obama's claims to run a transparent administration poll as a laugh riot.)

Truthfully, the government didn't help its case by mistreating Manning during detention, prompting the judge to award Manning with 112 days credit toward the ultimate sentence because of the illegal abuse. Yes, that's a small fraction of the 35 years eventually passed down. But it doesn't look good when jailers are forced to explain in court how they were ordered to keep a prisoner confined to a cell, naked and shivering.

Just as troubling were the lengths to which the federal government went to investigate people who merely supported Manning. Officials stalked David Maurice House so they would know when he'd left the country, making himself vulnerable to a search of his digital data at the border, beyond the protections of the Fourth Amendment.

Even after sentencing, in prison, Manning became spokesperson not just for government transparency, but for gender identity—that is the right to choose your own.

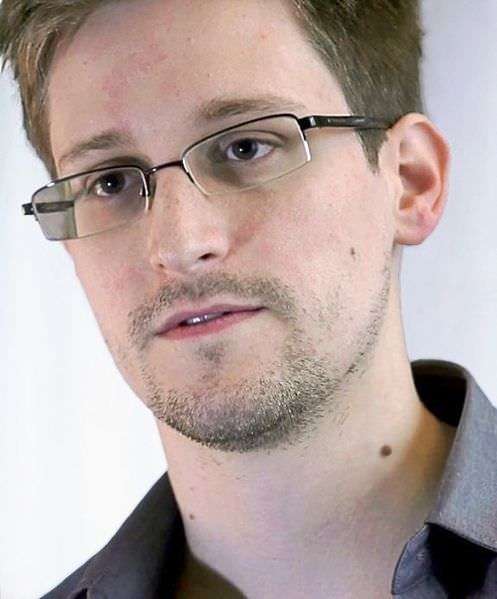

Edward Snowden is, of course, the 2013 poster child for deliberately working against the state. He did so in order to let Americans, and the world beyond, know just how subject to super-creepy spying they are by the United States government. Snowden took jobs that gave him access to troubling National Security Agency secrets—and then released them to journalists for publication after he left the country and whatever unpleasant fate might be planned for him. He's even believed to have retained an info-bomb of truly sensitive material that will "detonate" if the feds try to grab him from his current refuge in Russia or otherwise silence the whistleblower.

In years past, government officials would have counted on the public to boo and hiss at Snowden on command. You're not supposed to spill the government's secrets to the world at large.

But Americans are horrified by those secrets—published revelations of NSA snooping have helped drive public revulsion at "big government" to record high levels. Snowden himself gets more of a split decision, but over a third of people tell Reason-Rupe that what he did makes him a patriot (with even higher support for him among younger Americans). That's almost equal to the percentage of respondents who give him a thumbs-down. Those would have been unthinkable numbers in a different era.

And if powerbrokers in D.C. want to call Snowden a "traitor," lawmakers on the outs with the leadership have been moved by his actions to try to curtail the surveillance state.

Swartz, Manning, and Snowden have all incurred personal consequences for their actions. So did Ross William Ulbricht, who as the (alleged) "Dread Pirate Roberts," ran the famous (and still-functioning) Silk Road online drug marketplace. Before his arrest on federal charges, the Dread Pirate Roberts developed a following for setting up an illegal Website that emphasized honesty and allowed users to rate dealers. He also led libertarian political discussions, backing his illicit economic activity with activist conviction.

Cody Wilson, of Defense Distributed, shares similar activist convictions, though he hasn't suffered legal consequences for introducing the world to functioning firearms created by people, on their own, with 3D printers. The same can be said of "Satoshi Nakamoto," the pseudonymous creator of the Bitcoin virtual (and anonymous) currency that has eased transactions in illegal goods and the protection of wealth from tax collectors. They may have (they definitely have) angered the powers that be, but governments have yet to find a practical way to criminalize innovation that enables activities they don't like.

Wilson, "Nakamoto," and their creations have also won wide world-wide followings, exlicitly linked to the authority-defying power of what they've done.

Flipping the bird to the state doesn't guarantee universal acclaim. It certainly doesn't ensure personal safety. But more than at any time in recent memory, defying governments and their laws has a constituency—a large one—that sees such action as necessary and even heroic.

Government officials may still act against the rebels. But instead of whipping up the public into a shared two minutes hate against a common foe, they're increasingly finding themseves viewed as the enemy by people who cheer acts of defiance.