Why Fentanyl Smuggling isn't War and Cannot Justify Extrajudicial Killing

Thus, Trump's attacks on boats in the Carribean have no moral or legal justification.

Donald Trump continues to order strikes on boats carrying supposed drug traffickers in the Carribean and the Pacific, killing an estimated 43 people so far. I have previously written about why these attacks are both illegal and unjust. See also insightful analyses by Brian Finucane at Just Security (here and here). Drug smuggling is, at most, a criminal law issue, not an act of war. And, in many cases, the people targeted either were not actually smuggling drugs or were not on their way to the US (US law cannot and does not forbid mere possession of drugs in international waters).

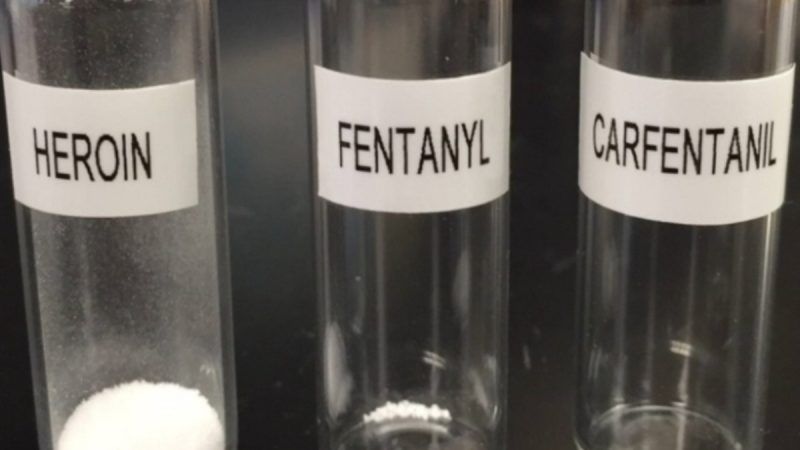

The most common answer to such critiques is that the strikes are justified because the supposed smugglers are transporting fentanyl, and fentanyl overdoses kill thousands of Americans each year. Thus, it is claimed, fentanyl smuggling represents a threat akin to terrorism (labeled "narco-terrorism" by the administration), and Trump is justified in using military force to forestall it.

This equation of drug overdoses with terrorist attacks overlooks the fundamental moral and legal difference between deaths that occur as a result of violent attack and those that occur because consumers voluntarily imbibed a dangerous drug. Many people die every year, at least in part because they chose to adopt dangerous consumer habits. For example, many thousands of deaths per year are obesity-related. Obesity is greatly exacerbated by bad diets. It doesn't follow that manufacturers and sellers of junk food are the moral equivalent of terrorists, and that the US government would be justified in killing them without any due process. The same goes for producers of many other products whose consumption contributes to poor health outcomes, such as alcohol, cigarettes, and more.

In the case of illegal drugs, the negative health effects are actually exacerbated by prohibition. The fentanyl crisis is itself largely a result of the War on Drugs, a predictable consequence of the "Iron Law" of prohibition, under which banning legal markets incentivizes dealers and users to turn to harder, more potent drugs.

In my view, the real evil here is the War on Drugs, which causes immense harm, and violates the fundamental principle of bodily autonomy. People should be able to decide for themselves whether the benefits of taking a given drug are worth the costs, including negative effects on health. The same goes for eating junk food, drinking alcohol, and so on. Ending the War on Drugs would simultaneously protect liberty and greatly reduce the role of organized crime and drug cartels in the drug trade - just as the end of alcohol Prohibition greatly curtailed the role of criminal organizations in that industry.

But at the very least, there is no moral or legal justification for turning the War on Drugs into a real war by executive fiat. Only Congress can authorize war, and it has not done so here (and for good reason).

But don't take my word for the importance of the distinction between terrorism and fentanyl smuggling. Take that of John Yoo! Prof. Yoo, a prominent conservative legal scholar, is the leading champion of sweeping executive power over national security issues. But he nonetheless concludes, in a recent Washington Post op ed, that Trump has gone too far, here:

These attacks risk crossing the line between crime-fighting and war. The Trump administration is right that illicit drugs are inflicting more harm on the U.S. than most armed conflicts have. More than 800,000 Americans have died of opioid overdoses since 1999….

But the U.S. cannot wage war against any source of harm to Americans. Americans have died in car wrecks at an annual rate of about 40,000 in recent years; the nation does not wage war on auto companies. American law instead relies upon the criminal justice or civil tort systems to respond to broad, persistent social harms. In war, nations use extraordinary powers against other nations to prevent future attacks on their citizens and territory. Our military and intelligence agents seek to prevent foreign attacks that might happen in the future, not to punish past conduct….

As an official in the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, I was at my desk on Sept. 11, 2001. I advised that the U.S. could wage war against al-Qaeda without blurring the distinction between crime and war. After 9/11, the U.S. declared that it would wage war for the first time against an organization, rather than a nation. But the drug cartels alone do not present a similar challenge that rises to the level of war.

Crime is generally committed for personal gain or profit rather than a political goal. Drug cartels employ murder, kidnapping, robbery and destruction to create a distribution network, grab turf from other gangs, intimidate rivals or customers, and even retaliate against law enforcement. National security threats, such as terrorist groups, might resemble organized crime in some respects, but the Mafia and drug cartels are unconcerned with ideology and are primarily out to satisfy their greed.

Like a nation, a terrorist group conducts attacks that are highly organized, military in nature, and aimed at achieving ideological and political objectives. A terrorist group might resort to crime for funding, such as stealing money or defrauding charities, but terrorist groups use the money for military and intelligence efforts rather than the mere accumulation of wealth. An enemy's conscious political objective distinguishes war from general crime, which exists at a persistent level, and which society will never completely extinguish.

I think Yoo's analysis here understates the harm caused by the War on Drugs, even in its conventional criminal-justice form. But he's absolutely right about the distinction between crime and war.

There is no war here. Thus, Trump's boat strikes do not even qualify as war crimes. They are just plain ordinary crimes, a form of extrajudicial murder.