A Night in Jerusalem

History and a city at war.

On a late summer night Jerusalem casts a magic spell. The first day of autumn is less than a week away but the daytime temperature is close to 90 degrees Fahrenheit, and the sun is relentless. Then the cool breeze of evening comes and it's like the soft touch of a cat's whiskers.

Jerusalem is a city that needs to be seen on three levels. The street is a cacophony of cars of course but also the thrust and parry of conversation in the cafes on Bethlehem Road. Viewed from above, from the YMCA tower, say, an elegant art deco structure designed by the same architect who built New York's Empire State Building, the city looks like a forest of stone. The walls of the Old City, the domes and spires of church, mosque, and synagogue, the graves of the Mount of Olives, the ubiquitous construction cranes ("Israel's national bird," as the joke goes) and the slabs of limestone that line the buildings they help to erect, the separation wall between Israel and the Palestinian territories.

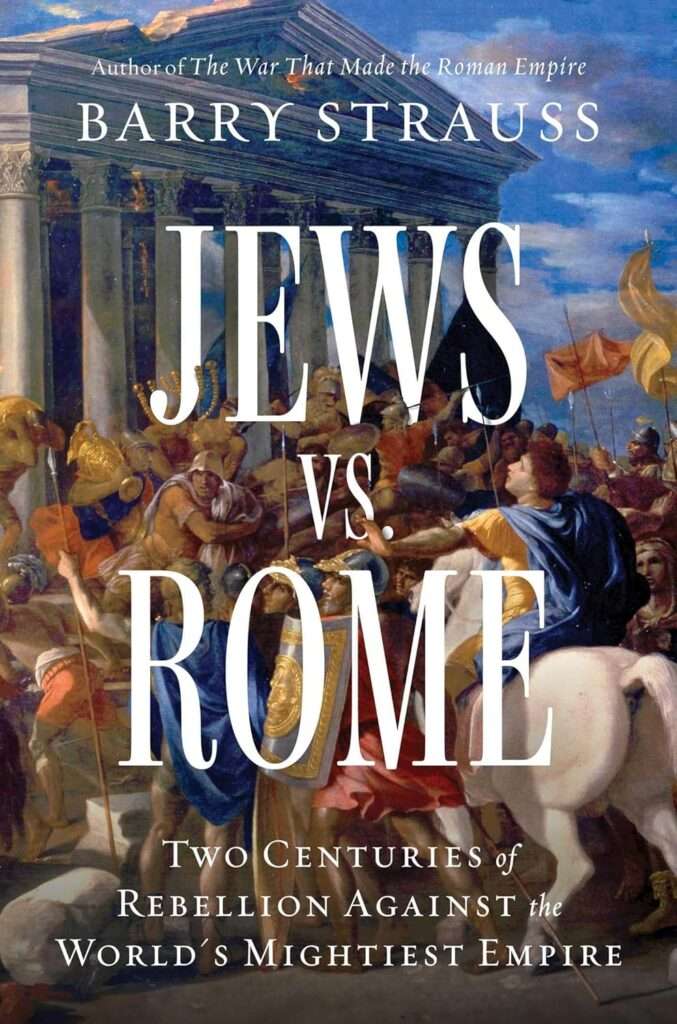

But as a historian, I am drawn to what lies underneath Jerusalem. It is not difficult to find mementoes of the Great Revolt of 66-70 in which the Romans laid siege to the city, captured it and destroyed the whole town, including the Second Temple. I write about that revolt, and two other Jewish revolts against Rome, in my new book, Jews vs. Rome: Two Centuries of Rebellion Against the World's Mightiest Empire (Simon & Schuster, 2025). The death throes of Jerusalem come alive under the streets of the Old City.

You can visit, for example, the ruins of the mansions of the wealthy, which in their heyday looked across a valley at the Temple Mount. The splendor of these dwellings still survives in the fragments of mosaics, frescoes, and stucco. The owners were pious Jews, as shown by the presence of ritual baths and stone vessels. They were probably priests, maybe including the High Priest. You can also see traces of the fire that brought the buildings down.

Not far away is the so-called Pilgrim's Road, which led from the Pool of Siloam through the City of David to the Western Wall of the Temple Mount. It's a path that was followed by people coming to Jerusalem for one of the three annual pilgrimage festivals. Jesus might have trod this road.

Among many striking finds, the excavators discovered "blackened seeds" and "rich botanical evidence" that can be dated to the time of the revolt. These may be precious material evidence of what the historian Josephus, a contemporary, describes in his classic book, The Jewish War. That is, as Josephus reports, the rebels themselves burned the city's grain supply, perhaps in a series of inter-factional disputes—a counter-productive and even suicidal gesture to be sure.

How, I wonder, did the people of Jerusalem go about their business during the four years of the revolt? Some panicked, some fled, but most of them stayed as if nothing was happening, as if the Roman army wasn't prowling the country. Why? Maybe the answer lies in what I saw in Jerusalem one recent evening.

I saw the streets full of shoppers. Arabs and Jews crowded the upscale boutiques of the Mamilla Mall. Left in ruins by the fighting in Jerusalem in Israel's War of Independence, between 1949 and 1967, the area was No-Man's-Land between Israel and Jordan. Now it is Jerusalem's toniest emporium.

I saw two groups of street musicians. One group was boisterous and joyful. A crowd of people followed it clapping and dancing through the mall toward the Jaffa Gate of the Old City. The other group, seated in a circle outside the Gate, sang softly in the night air.

That evening, the war in Gaza City was about to heat up, and everyone knew it. Even readers of goodwill might wonder how people at war—and the mall included soldiers in uniform—might go out for a night on the town. Yet there is nothing new about wartime societies enjoying precious moments of peace. As far back as the Trojan War, soldiers partied before going out to battle.

Not that Israelis aren't hurting after nearly two years of war. Most people are tired, some are traumatized, some fear for the future in an ever-more hostile region and world, and many are angry at their government (what else is new?). Yellow ribbons for the hostages are tied to the door handles of many cars, and posters along the streets recall those still in captivity or whose bodies have not been returned. Other posters show the youthful faces of soldiers who have died in battle. Political divisions in Israel continue as usual; I can't count the number of protests that I saw.

And yet, for all the pain and division, the indefatigable Jewish spirit, stubborn, resilient, and optimistic, prevails.

The morning after I visited Mamilla, the valleys of Jerusalem were full of fog. You could feel that the seasons changing. Both the start of autumn and the Jewish New Year are now just days away. May it be a happy and healthy year, one of a new beginning for Gaza, the safe return of the hostages and, above all, a year of peace for Israel and the whole region.