Slippery Slope June: Cost-Lowering Slippery Slopes

[This month, I'm serializing my 2003 Harvard Law Review article, The Mechanisms of the Slippery Slope; in Wednesday's post and yesterday's post, I laid out some examples, definitions, and general observations. Now, I turn to more details on one specific kind of slippery slope mechanism—cost-lowering slippery slopes.]

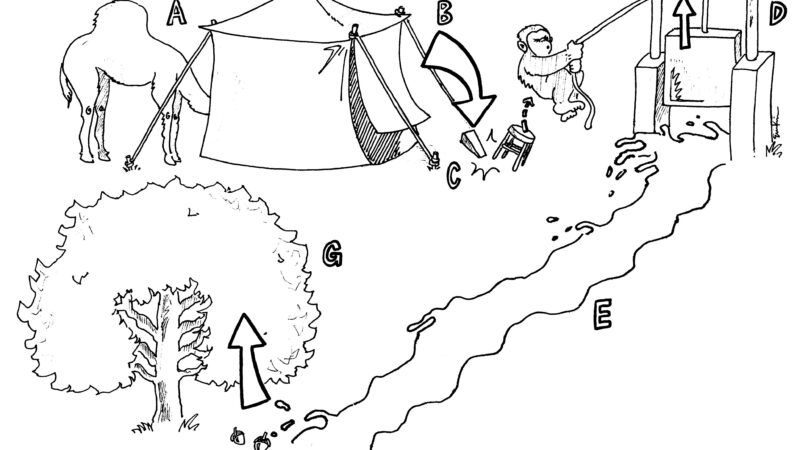

[1.] An Example.—Let's begin with the slippery slope question mentioned in the Introduction: does it make sense for someone to oppose gun registration (A) because registration might make it more likely that others will eventually enact gun confiscation (B)? A and B are logically distinguishable, but can A nonetheless help lead to B?

Today, when the government doesn't know where the guns are, gun confiscation would require searching all homes, which would be very expensive; relying heavily on informers, which may be unpopular; or accepting a probably low compliance rate, which may make the law not worth its potential costs. And searching all homes would be both financially and politically expensive, since the searches would incense many people, including some of the non-gun-owners who might otherwise support a total gun ban.

But if guns get registered, searching the homes of all registrants who don't promptly surrender their guns would become both financially and politically cheaper, especially if a confiscation law bans just one type of gun, covers only a region where guns are already fairly uncommon, or perhaps covers only a subset of the population (such as public housing residents). Confiscation has eventually followed gun registration in England, New York City, and Australia. While it's impossible to be sure that registration helped cause confiscation in those cases, it seems likely that people's compliance with the registration requirement would make confiscation easier to implement, and therefore more likely to be enacted. And Pete Shields, founder of the group that became Handgun Control, Inc., openly described registration as a preliminary step to prohibition, though he didn't describe exactly how the slippery slope mechanism would operate.

Under some conditions, then, legislative decision A may lower the cost of making legislative decision B work, thus making decision B cost-justified in the decisionmakers' eyes. There's no requirement here that A be seen as a precedent, or that A change anybody's moral or pragmatic attitudes—only that it lower certain costs, in this instance by giving the government information.

[2.] A Diverse Preferences Explanation for Cost-Lowering Slippery Slopes.—The cost-lowering slippery slope is driven by voters' having a particular mix of preferences; a numerical example might help demonstrate this.

Consider a hypothetical proposal to put video cameras on street lamps in order to help deter and solve street crimes. The plan obviously isn't perfect, but it seems promising: smart criminals will be deterred and dumb ones will be caught.

On its own, the plan might not seem that susceptible to police abuse, at least so long as (for instance) the tapes are recycled every day and the cameras aren't linked to face-recognition software. Under those conditions, the cameras might be effective for fighting low-level street crime, but they wouldn't make it that easy for the police to track the government's enemies. People might therefore support installing these cameras (decision A), even if they would oppose implementing face-recognition software or permanently archiving the tapes (decision B). {I take no position here on which of 0 (no cameras), A, and B is substantively better; I am only describing how some people might act to have the best chance of implementing their own preferences.}

But once the legislature implements A and the government invests money in installing thousands of cameras, wiring them to central video recorders or to phone lines, and protecting them from vandals, implementing B becomes much cheaper economically, and thus easier politically. Imagine that, if money were no object, voters would have the following (highly stylized) mix of opinions:

- 20% of the public would oppose even decision A, because they don't want the police videotaping street activity at all;

- 20% of the public would support A but oppose B, because they like videotaping only if tapes are quickly recycled and no face-recognition software is used;

- 60% of the public would support B, because they like police videotaping more generally, and would certainly support A if they can't get B.

And imagine that 30% of the second and third groups would nonetheless oppose decisions A and B because they cost too much. The mix of preferences would thus be:

| Group # | Preference | Would support in principle and given the cost (e.g., if there are no cameras yet, and we're in position 0 | Would support in principle, if there were no extra cost (e.g., if the cameras are already up, because A was already implemented) |

| I | 0: no cameras | 20% | 20% |

| II | A: cameras, no face-recognition and no archiving | 14% | 20% |

| III | A: cameras, with face-recognition and archiving | 42% | 60% |

If the people in group II focus only on the vote on A, members of that group who don't mind the financial cost will vote "yes"; and with group II's 20% x 70% + group III's 60% x 70% = 56% of the vote, A would be enacted. {I assume here that 56% support is enough for the proposal to win—not certain, but likely.} But a few years later, when someone suggests a move to B at no extra cost, that proposal would also be enacted, since 60% of the public would now support it, given that there's no more fiscal objection.

Thus, the group II people must make a tough choice: do they want A so much that they're willing to accept the risk of B as well, or are they so concerned about B that they're willing to reject A? The one item that is off the table is the one group II most prefers, which is A alone with no danger of B. The cost-lowering slippery slope has eliminated that possibility, at least unless there's a constitutional barrier to B or unless the government intentionally makes B expensive to implement, for instance by buying cameras that are incompatible with the technology needed for B.

This is, of course, just a hypothetical; obviously, if people's preferences break down differently, the slippery slope might not take place. The point here is simply that this sort of slippery slope may happen under plausible conditions—and that people who support A but not B should therefore consider the possibility of slippage.