Can you be prosecuted for repeated unwanted emails to government offices or officials?

If I keep phoning you to say offensive things to you, I might be prosecuted for telephone harassment (especially if you've told me to stop calling). Similar laws in many states apply to unwanted email; sometimes, you can get a restraining order against me to stop talking to you. Some "harassment" and "stalking" bans likewise restrict unwanted in-person speech. These laws have generally been upheld by lower courts; and in Rowan v. U.S. Post Office Dep't (1970), the Supreme Court upheld a law that let anyone basically order any mailer to stop mailing them, and if the mailer continued, that would be a crime.

Offensive speech about people is generally constitutionally protected, unless it falls within one of the narrow First Amendment exceptions, such as threats or defamation. But offensive speech to people can generally be restricted.

But what if the offensive speech is to a government office, to a government official or (sometimes) to a candidate? Let's set aside speech that falls within an existing First Amendment exception, such as true threats of criminal attack, or so-called "fighting words" (face-to-face personal insults that are likely to start a fight). Can calling government offices or officials to insult them - especially after being told to stop - be punished the way that calling a private individual to insult them might be?

I think the answer should be "no," and the lower court precedents on the subject seem to agree; but in two recent cases, government officials seem to think that such speech can indeed be criminalized.

1. Ion Popa left seven messages containing racist insults on the answering machine of the head federal prosecutor in D.C. - Eric Holder, who eventually became attorney general. He was convicted of telephone harassment, which banned all anonymous calls made "with intent to annoy, abuse, threaten, or harass." But the D.C. Circuit (1989) expressly held that the First Amendment prevented the statute from applying to "public or political discourse," such as condemnation of political officials (even left expressly for that official).

2. Darren Drahota sent a couple of anonymous insulting emails to William Avery, Drahota's former political science professor, who was running for the Nebraska Legislature at the time. (Avery was eventually elected and served two terms.) Drahota was convicted of disturbing the peace for sending those emails, but the conviction was reversed in 2010 by the Nebraska Supreme Court. (I have a soft spot in my heart for this case, because it was the first First Amendment case I ever argued in court.)

3. William Fratzke was convicted of harassment "because he wrote a nasty letter to a state highway patrolman to protest a speeding ticket." The Iowa Supreme Court (1989) reversed, on First Amendment grounds.

4. Thomas Smith was convicted of disorderly conduct and "unlawful use of a computerized communication system" for leaving two vulgar, insulting comments on a police department's Facebook page. A one-judge Wisconsin Court of Appeals decision (2014) reversed. (Note that such insults aren't unprotected "fighting words" because they aren't face-to-face and thus aren't likely to lead to an immediate fight.)

5. Harvey Bigelow sent two letters to Michael Costello, an elected town council member; both were insulting, and one was vulgar. Bigelow was convicted of criminal harassment, but the Massachusetts high court (2016) reversed: "Because these letters were directed at an elected political official and primarily discuss issues of public concern - Michael's qualifications for and performance as a selectman - the letters fall within the category of constitutionally protected political speech at the core of the First Amendment." And this was true even though the letters were sent to him at home:

It is true that the letters were sent to Michael [Costello] at his home, a location where the homeowner's privacy is itself entitled to constitutional protection. Cf. Rowan v. United States Post Office Dep't (1970). Cf. also Cohen v. California (1971) ("[T]his Court has recognized that government may properly act in many situations to prohibit intrusion into the privacy of the home of unwelcome views and ideas which cannot be totally banned from the public dialogue"). But Michael was an elected town official, and as Michael himself testified, receiving mail from disgruntled constituents is usual for a politician. A person "who decides to seek governmental office must accept certain necessary consequences of that involvement in public affairs … [and] runs the risk of closer public scrutiny than might otherwise be the case." Here, given Michael's status as a selectman and the content of the letters, it cannot be said that Michael's "substantial privacy interests [were] invaded in an essentially intolerable manner."

Other letters that Bigelow sent to Costello's wife, however, were found to be properly treated as true threats of criminal conduct (because they went beyond just insults and vulgarities), which could lead to criminal punishment, though the conviction as to those letters was reversed on other grounds.

And these are just the appellate cases; for federal district court cases, see Barboza v. D'Agata (S.D.N.Y. 2015) (disagreed with on appeal by the Second Circuit as to qualified immunity, but not as to the First Amendment) (writing "fuck your shitting town bitches" on a traffic ticket is protected by the First Amendment against an aggravated harassment charge); U.S. Postal Serv. v. Hustler Mag., Inc. (D.D.C. 1986) (sending Hustler Magazine to congressional offices is protected by the First Amendment, even when the recipients demand that such mailings stop, though sending material to ordinary citizens after a demand to stop is unprotected).

6. The cases that I've seen that allow punishment for such speech fall into two categories: (a) Offensive phone calls to government officials' homes (see, e.g., Hott v. State (Ind. Ct. App. 1980)), so the protection there is not as clear as for speech to the offices or email to an account used for professional as well as personal correspondence. (b) Extremely frequent phone calls that have the potential to tie up phone lines and thus prevent real calls from getting through reliably ( (N.Y. App. 1977) (upholding conviction for calling police department 27 times in 3½ hours to make a complaint, despite having been told that the matter was civil rather than criminal); City of E. Palestine v. Steinberg (Ohio Ct. App. July 21, 1994) (upholding conviction for calling 911 eight times in half an hour for nonemergency purposes after having been told to stop).

* * *

But, despite the precedents given above - and despite broader First Amendment principles of freedom to criticize government - some government officials continue to think that offensive speech to them (and to their offices) can indeed be criminalized, at least in some situations. Two current controversies illustrate this.

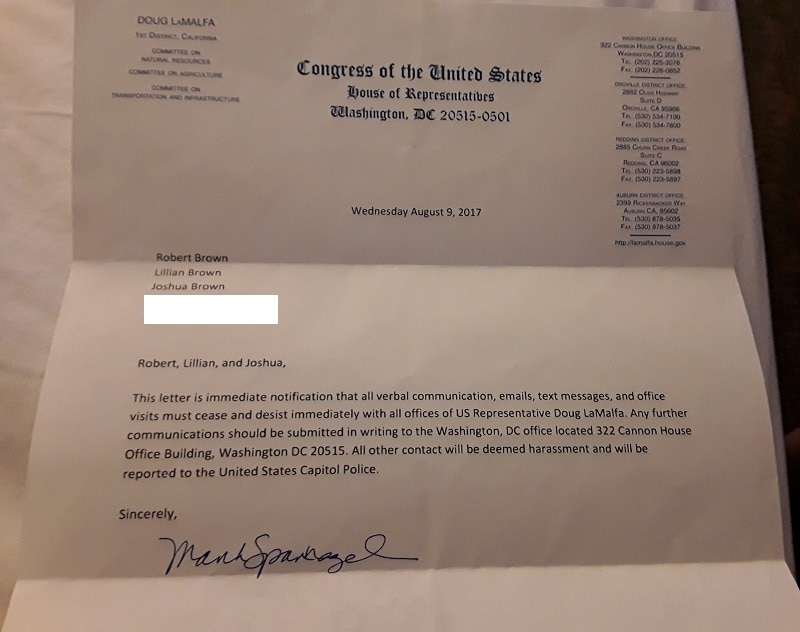

A. The Brown family, Northern California constituents of Rep. Doug LaMalfa, received this letter:

I tried to figure out the backstory behind the letter, which seems to have been prompted by contacts from Joshua Brown, the 13-year-old son of Robert and Lillian Brown; but I couldn't get enough details on the record other than to say that (1) Joshua had indeed contacted office staff often, and (2) there's a dispute about some of the details of the contacts. Here's how an article in the local newspaper, The Record Searchlight (Amber Sandhu & Jenny Espino), summarizes it:

Joshua, by his own admission, called LaMalfa's office a lot, Brown said. He also had contact with Erin Ryan, LaMalfa's district representative, who made her cell phone available, Brown said.

Ryan said her cell phone number is readily available on her business card, but refused to comment on this story.

Mark Spannagel, LaMalfa's chief of staff, signed off on the cease-and-desist letter sent to the Brown family. He said he was unable to go into detail about what caused the U.S. Capitol Police to issue the letter, but clarified his stance that the letter was directed at the Brown family, not just Joshua himself….

"Due to privacy we cannot get into the full details of the situation. These constituents are always welcome to have written communication. The extreme volume, tone and physical actions led the Capitol Police to recommend that it was best to limit communications to only the D.C. Office and via writing," Spannagel said in [a] prepared statement.

Spannagel said this is the third time a cease-and-desist directive has been sent from LaMalfa's office and this was a "very, very, very rare exception."

But Brown argues there was no "physical action" as Spannagel states, and that he and Joshua had been to LaMalfa's office only once.

Yet whether or not the contacts with office staff might justify a demand that the Browns not physically approach them, it's hard for me to see how there could be any basis for criminally punishing the Browns for sending any further "emails" (even if communication by letters to D.C. were still allowed). A congressman and his staff have no legal obligation to pay attention to constituents' emails; they could delete them unread, if they'd like. Threatening criminal prosecution for all such future emails, though, strikes me as unjustifiable (even if the plaintiff is allowed to use a more expensive and time-consuming process such as sending a letter to the main office, a process that LaMalfa's own site says "is the slowest method for contacting me").

B. In Ohio, though, such a criminal prosecution actually seems to be happening: Jeffery Rasawehr is being prosecuted for, among other things, sending eight messages to the Mercer County Sheriff's Office over the span of eight days (apparently using the online form at http://www.mercercountysheriff.org/home/contact-us), with statements such as,

I have been reading your legal work--are you really this stupid--damn you are pathetic--if you were in the real world you would be an absolute failure good thing you can hide behind a badge like the little man you are.

Rasawehr had apparently contacted the sheriff's office many times before then and was instructed not to contact it further except in an emergency. (Rasawehr is also being prosecuted for several phone calls to the office, as well as online social media postings sharply criticizing his sister, mother, ex-wife and others, plus some unwanted messages sent directly to those people; I'm focusing here on the prosecution for emails to the sheriff's department.)

The government's theory is that the unwanted emails constitute obstructing official business:

No person, without privilege to do so and with purpose to prevent, obstruct, or delay the performance by a public official of any authorized act within the public official's official capacity, shall do any act that hampers or impedes a public official in the performance of the public official's lawful duties.

As I understand it, the argument is that the sheriff's department has to monitor messages that come in, since there could be complaints of real crimes (including emergency complaints). Indeed, I take it that the department probably couldn't, consistently with its duties, just categorically block all emails from Rasawehr, since maybe the 30th time the boy cries "wolf," there really will be a wolf there. And, the theory goes, processing insults from Rasawehr - even just to recognize them as empty insults - takes time that should be used to deal with real crime.

But I don't think this can be enough. First, I doubt that Rasawehr was speaking with the purpose to prevent, obstruct or delay the sheriff's department in performing its duties. "Purpose" requires a "specific intention to cause a certain result." Merely being "aware that the person's conduct will probably cause a certain result" doesn't itself qualify as "purpose" (under Ohio law, it's labeled "knowledge"). Rasawehr may well have had the specific intention to annoy his listeners, but there is little reason to think that he had the specific intention to prevent or delay them from handling other matters.

Second, even if one does think that sending a message to a sheriff's department knowing that the department will need to take time to read it should qualify under the statute, consider just how much this would criminalize. The statute applies to any public official, so any time someone sends an insulting message to a public official, he would be committing a crime. (Indeed, a message of praise would equally qualify, since that message, too, would distract the official from his normal duties.)

Recall that each message to the sheriff's department is being treated, under the criminal complaint, as a separate crime in itself. But even if Rasawehr was prosecuted for the entire course of conduct, on the theory that eight messages is too many even if one is protected, I think that can't be right. Having to see the public's views, even harsh views, has to be a part of public officials' job, at least in a democracy.

Now, one can imagine situations where the volume of messages is so vast that it could be criminalized, not because of the content but precisely because of the volume: A denial-of-service attack, in which people send thousands of messages to a computer precisely to keep it from handling ordinary traffic, may be made illegal. Excessive phone calls to 911 lines, or in-person communications with a police officer who is handling an emergency, might also potentially be punishable, because the very fact that they have to be dealt with immediately makes them especially distracting.

But Rasawehr's messages, submitted through the website, didn't tie up an emergency line, or even use a channel designed solely for emergency use: The Sheriff's Office main page links to the contact form with the description, "We want you to use this site as a direct link to us. Therefore, if you have questions, comments, or suggestions we want to hear from you. Contact us page." Nor did Rasawehr's messages block the arrival of other messages, the way a denial-of-service attack would.

And I don't think that an email to a government agency, or even several emails in a day, that can be read in than a minute or less - without distracting from any pending emergency - and that can be immediately recognized as general criticism rather than as evidence of a crime or a call for help, can be properly punished. As the sheriff's site implicitly recognizes, part of the government's duties is to accept "comments" from the public, even comments that are insulting and repeated.

The Iowa Supreme Court acknowledged this in Fratzke, "Our Constitution does not permit government officials to put their critics, no matter how annoying, in jail," including when the critics write messages directly to the officials. And, the U.S. Supreme Court said the same in City of Houston v. Hill, even with regard to in-person speech:

[T]he First Amendment protects a significant amount of verbal criticism and challenge directed at police officers. "Speech is often provocative and challenging…. [But it] is nevertheless protected against censorship or punishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest."