Trump's Trade War Means American Companies Are Making Less Money on Cars and Trucks

Ford expects to lose $1 billion due to higher steel prices, while Caterpillar's stock dropped sharply this week after it said tariffs cost it $40 million.

Just weeks after President Donald Trump took office, Ford Motor Company flattered the jobs-obsessed chief executive with the announcement that it would invest $850 million to upgrade a Michigan plant amid plans to bring production of two pick-up trucks, the Ford Ranger and the Ford Bronco, back to the United States.

The plans were already in place before Trump was elected, but that didn't matter much to Trump. "Big announcement by Ford today," Trump tweeted on March 28, 2017. "Car companies coming back to U.S. JOBS! JOBS! JOBS!"

Less than a year later, the Trump administration thanked Ford by announcing plans to impose 10 percent tariffs on imported aluminum and 25 percent tariffs on imported steel—tariffs that Ford executives say will cost the company more than $1 billion over two years.

The broad-based steel and aluminum tariffs imposed earlier this year have fallen off the front page amid the Trump administration's continued escalation of a trade war that's now more focused on Chinese-made items like electronics, home goods, and industrial imports. But this week brought a fresh reminder of the economic pain that the higher import taxes on steel and aluminum continue to cause for American industries that require those raw materials to build other products.

Companies that build cars, trucks, motorcycles, and other vehicles have been particularly hard hit—as investor information released this week by Ford, as well as heavy by machinery builder Caterpillar and motorbike-maker Polaris, demonstrate.

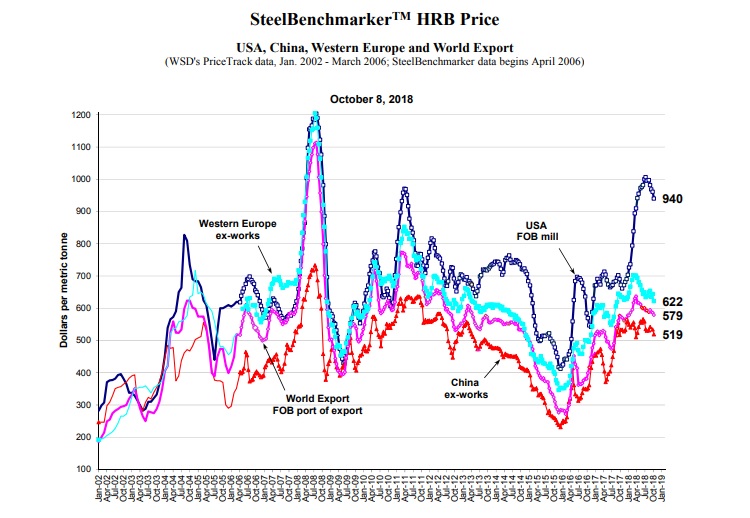

"U.S. steel costs are more than anywhere else in the world," Joe Hinrichs, Ford's president of global operations, told Bloomberg earlier this week.

After rocketing upwards in the months after Trump announced the new tariffs on steel, American-made steel has seen a mild drop in price but remains significantly more expensive than steel from other regions around the globe. The tariffs on imported steel have allowed domestic steelmakers to increase prices, and greater demand for domestic steel has further fueled the price increase (though there is still little to no evidence that American steelmakers are expanding production or hiring more workers).

Some American manufacturers are trying to avoid taking a hit on those higher prices by forcing suppliers to eat the cost of tariffs, though it's not clear how successful that strategy can be over the long term. That's what Polaris, a Minnesota-based maker of snowmobiles and motorbikes, has been trying to do, according to investor information reported this week by Bloomberg. Even so, the company estimates that tariffs have cost it about $40 million this year, and Polaris' stock price has fallen by 31 percent since January.

Heavy machinery builder Caterpillar estimated this week that tariffs added $40 million to its raw materials cost, and announced that it would have to increase prices next year to keep up. The news caused the company's stock to drop sharply Tuesday, and it has now lost about 30 percent of its value since January.

None of this should come as much of a surprise, since the one-and-only goal of tariffs is to increase the price of imported goods in order to give domestic producers a competitive advantage. The problem, of course, is that there are many, many more American businesses that consume steel and aluminum—and it's those businesses that pay for the cost of tariffs, even if Trump continues to push the fallacy (as he did again in a tweet on Tuesday) that other countries somehow bear those costs.

Billions of dollars are, and will be, coming into United States coffers because of Tariffs. Great also for negotiations - if a country won't give us a fair Trade Deal, we will institute Tariffs on them. Used or not, jobs and businesses will be created. U.S. respected again!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 23, 2018

Yes, billions of dollars are flowing into the Treasury because of tariffs. But as the latest earnings reports and comments from Ford, Polaris, and Caterpillar readily indicate, those dollars are being drained out of American companies—the very companies that are providing the blue collar jobs that Trump likes to tout.