Steve Ditko, RIP

The Objectivist comic book artist, co-creator of Spider-Man and Dr. Strange, left an indelibly brilliant mark on popular culture.

Steve Ditko, the comic book artist who is also the most influential popular artist specifically and deeply influenced by Ayn Rand's Objectivism, was found dead in his New York apartment late last month at age 90.

His greatest claim to fame was his co-creation in the early 1960s of Spider-Man and Dr. Strange with writer Stan Lee at Marvel Comics. Ditko's fertile imagination is to this day keeping thousands of people employed and multi-millions of dollars flowing through the Marvel cinematic universe's reliance on his concepts.

Not that Ditko worried about that sort of thing; he had done the work he had done, for hire, and had let go any public sense of being owed anything for it. He did want it on the record that he had co-created those characters when he saw Lee seeming to imply otherwise, but never publicly fought for any monetary recompense for it. But he deserved, and to a large degree got, the adoration of generations of comics fans, who he avoided, almost never appearing in public or allowing himself to be interviewed.

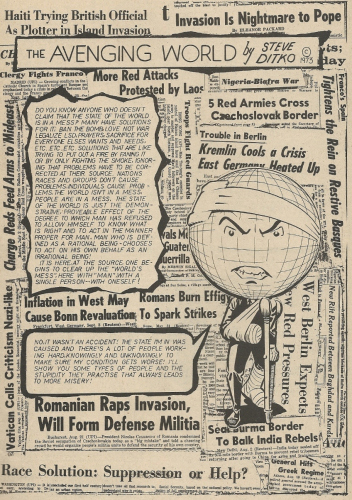

Ditko was also, once upon a time, a Reason contributor, in our early days. Our September 1969 issue (page 6) featured his energetically Randian 10-page story "The Avenging World," blaming the world's evils on equivocating "neutralist" compromisers who refuse to take firm and decisive sides between right and wrong.

The Watchmen protagonist Rorschach was Alan Moore's take on Ditko's DC Comics character The Question and, as I argued at Reason, Moore's attempt to present what a thoroughgoing Objectivist hero would be like in real life. (Rorschach also drew on Ditko's self-owned Objectivist hero Mr. A.)

When Reason contributing editor Peter Bagge wrote and drew a Spider-Man comic book for Marvel, he re-imagined Peter Parker as Bagge's own version of a character consumed, as Ditko was, by Objectivism.

Ditko was one of the very few sui generis cartoonists. While Jeet Heer in a thoughtful summation of his career and influence at New Republic notes Ditko being inspired by Jerry Robinson, Will Eisner, and Joe Kubert, to my eyes by the late 1950s, in his science fiction and weird mystery work for Charlton and Marvel Comics, Ditko was drawing in as explosively unprecedented a manner as anyone in comics history, with an endlessly rich and startlingly fresh way of representing the human imagination, quirky and eldritch, groundedly appealing but profoundly unsettling, distinct and in every detail exhibiting a mind that was just not like everyone else's.

No one in the superhero field even tries to get close to Ditko's style anymore, though as Heer also notes Ditko's draftsmanship and character design sense can be detected in some "alternative" cartoonists as Dan Clowes, Ben Katchor, and Gilbert Hernandez.

He walked away from his big Marvel creations in 1966 and while he continued to work for many other publishers, including Marvel again in the 1970s and '80s, Ditko abandoned the commercial comic industry by the end of the 1990s. Even in the late 20th century he mostly indulged in his own curious near-outsider-art presentations of his philosophy and thoughts. As comics critic and historian Douglas Wolk put it in his book Reading Comics, Ditko in his later years reduced (or possibly refined) his work to "pure nerve-wracking style: arguing faces, abstract doodles, hectoring moralism."

I noted at Reason his 85th birthday with many links of Objectivist interest. The nature of his post-Marvel career has been likened by some to Rand's Fountainhead hero Howard Roark working in the quarry, or Atlas Shrugged's John Galt taking his genius from the masses, doing whatever honest work he could even if not able to work to the height of his abilities and powers as a creator for the general public. He was willing to not be recognized by the world as long as it meant keeping his creative integrity intact. For reasons of personal integrity known only to him, he refused to sell any of his own original art pages, which could have made him a rich man.

The book Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko (Fantagraphics) details how Ditko in superhero comics such as Blue Beetle and Hawk and Dove worked Objectivist themes of the corruption of modern art, the necessity for rigorous rationality, and how evil works often through the "sanction of the victim" who refuses to recognize, name, and stand up for what's right.

Ditko's most Randian characteristic, though, is that he worked to the best of his unique individualistic creative powers, and in doing so shook up the world, making himself, if not the, at least a sustaining fountainhead of modern comics art.