Gawker Documentary Fails to Make Case for Publishing Sex Tape

Film favors martyrdom over careful analysis.

Nobody Speak: Trials of the Free Press. Available now on Netflix.

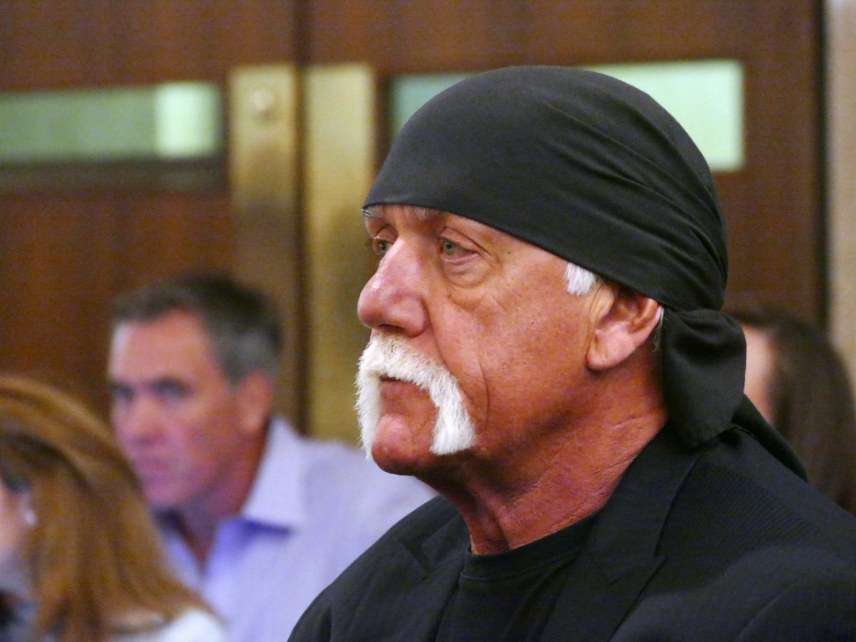

I'm afraid that merely to disclose the subject of the Netflix documentary Nobody Speak: Trials of the Free Press is about—the dire threat to the First Amendment posed by a jury's decision that a website did not have a right to show a stolen video of professional wrestler Hulk Hogan's penis in action—is to give away the entire plot: Yes, this is the latest and greatest chapter in the news media's eternal proclamation of martyrdom at the hands of prigs and fascists. And yes, it rises to such an awesome level of whining self-aggrandization that it threatens to spoil the good name of hogwash.

So, spoiler alert.

The case that's the subject of Nobody Speak is possibly the most fascinating and least significant in the three-century history of media litigation. It's full of depraved sex, villainous intrigue, and lurid betrayals. But its ultimate contribution to legal canon was not exactly epic. As longtime media lawyer Charles Glasser (an interview of whom would have been a welcome addition to Nobody Speak) wrote after the verdict, the case's lesson was simple: "Don't publish secretly-made sex tapes."

The story begins in 2012, when celebrity wrestler Hogan (nom de real life: Terry Bollea) got an unusual gesture of friendship from his best pal, radio shock-jock Bubba the Love Sponge: Hey, wanna sleep with my wife? Hogan knew this was a frequent recreational activity of Bubba (nom de non-perv world: Todd Alan Clem) and the busty Mrs. Sponge and had previously declined to participate But this time, down on his luck—and wallet—after a series of business reverses and an expensive divorce, he agreed.

What Hogan didn't know was that the Sponges routinely and secretly taped these marital guest appearances. (After the case blew up, Bubba claimed Hogan knew all about the taping, but he wouldn't repeat it under oath during the trial.) That might not have mattered except that a copy of the recording, apparently stolen by one of Bubba's employees, found its way into the hands of the scabby gossip website Gawker.

Founded in 2002, Gawker regularly trafficked in sex tapes and such scoops as the grooming of Republican senatorial candidate Christine O'Donnell's pubic hair. Founder Nick Denton, the British journalist who built Gawker into the centerpiece of a $200 million online media empire, routinely defended his celebrity-bullying scandal sheet as a champion of truth and democracy in a world of lickspittle mainstream media. "Everybody knows what usually appears, certainly, in the establishment media bears little resemblance to what's really going on," he says in Nobody Speak. Speaking truth to Bristol Palin and Justin Beiber!

Gawker posted a chunk of the tape; Hogan's attorney asked it be taken down, and when Gawker refused, filed a breach of privacy lawsuit. What followed was a series of potboiler plot twists: Another sex tape, with racist remarks by Hogan that would get him booted out of pro wrestling; intimations that Gawker, wittingly or not, was acting as a stalking horse for blackmailers; an FBI sting against a sex-tape broker; and a series of legal stratagems by Hogan's attorneys that the Gawker legal team considered inexplicably stupid but which turned out to be brilliant.

The real stupidity occurred on the Gawker side of the courtroom, none so lethally damaging as the swaggering arrogance of the site's former editor, A.J. Daulerio, who wrote the story accompanying the Hogan sex tape. During his testimony, Daulerio insisted that images of boinking celebrities are always newsworthy.

Always? wondered Hogan's attorney. Well, maybe not if the celebrity was a child, Daulerio conceded dismissively. Under what age? asked the attorney. "Four," sneered Daulerio, a remark that nearly everybody agrees sent Gawker's case into a death spiral. In an interview in Nobody Speak, a wounded Daulerio insists that "Clearly, I'm kidding." So, there's a second lesson to be had in the Gawker case: Don't practice your stand-up act during sworn courtroom testimony.

The case ended with the jury finding for Hogan and awarding him an astronomical $140.1 million in total damages. And, in one final plot twist, it was revealed that Hogan's lawsuit was funded by Silicon Valley zillionaire Peter Thiel, who developed a distaste for Gawker after it outed him in 2007 with a story headlined "PETER THIEL IS TOTALLY GAY, PEOPLE."

Nobody Speak tells the complex and admittedly entertaining story of the lawsuit well enough, albeit mostly from the perspective of Gawker. It's in the analysis of what the case meant where it gets shrill and foolish.

Most fundamentally, it's in the documentary's assumption that the jury verdict punished Gawker for truthfully reporting the peccadillos of the rich and powerful. (If a broke pro wrestler can be considered either one.) If Gawker had merely written that Hogan slept with his best friend's wife, Hogan could not possibly have sued him; truth is an absolute defense against libel.

But the wrestler didn't sue for libel. He went after Gawker not for what it said, but for invasion of privacy in what it showed: an intimate act, performed in private, taped without his knowledge or consent and then stolen by third parties. If that's not a breach of privacy, then literally nothing is.

That there isn't (or at least, shouldn't be) any such thing as a legally enforceable right to privacy may be an arguable position—but then it should be argued, openly and plainly, not cloaked in a silly claim that in being punished for publishing an illicitly obtained picture of Hogan's junk, Gawker is being thwarted in the pursuit of "real journalism, journalism that exposes things that powerful people don't want known," as one of the Gawkerites grandiosely claims in Nobody Speak.

There's even less merit in Nobody Speak's contention, advanced loudly, one-sidedly and at length, that there was anything novel or sinister in Peter Thiel's funding of Hogan's lawsuit. The concept of third-party funding of lawsuits goes back to ancient Greece and has been practiced in the United States for hundreds of years. Does anybody really believe that Oliver Brown, a welder in a railroad repair shop, really paid for all the legal costs of Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark school-desegregation that bore his name?

The shocked, shocked progressives who decry third-party funding in Nobody Speak should have been asked if they're outraged that venture-capital companies and big law firms banded together (in return for a share of the winnings) to finance the class-action lawsuit in which Ecuadorean Indians were awarded $9.5 billion from Chevron as damages for oil spills in Amazon.

Banning third-party financial support of lawsuits would not only put the ACLU and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund out of business but would prevent threadbare litigants from setting GoFundMe accounts to raise legal fees. Even a lawyer taking a case on a contingency base—that is, loaning out his legal skills in hopes that he'll be paid back later—is a form of third-party funding.

And outlawing third-party help for legal costs might have backfired badly on Gawker, too, which had its own financial angel during the lawsuit: It funded its legal war chest by selling a chunk of itself to a Russian oligarch named Viktor Vekselberg for an undisclosed but no doubt hefty sum. How much money was involved? What control over Gawker's fearless editorial voice did Vekselberg get? Nothing about that in Nobody Speak, which sees American billionaires as an existential threat to freedom of the press but takes its own name quite literally when it comes to Russian billionaires.