How Thousands of Randos Like Me Landed in the Epstein Files

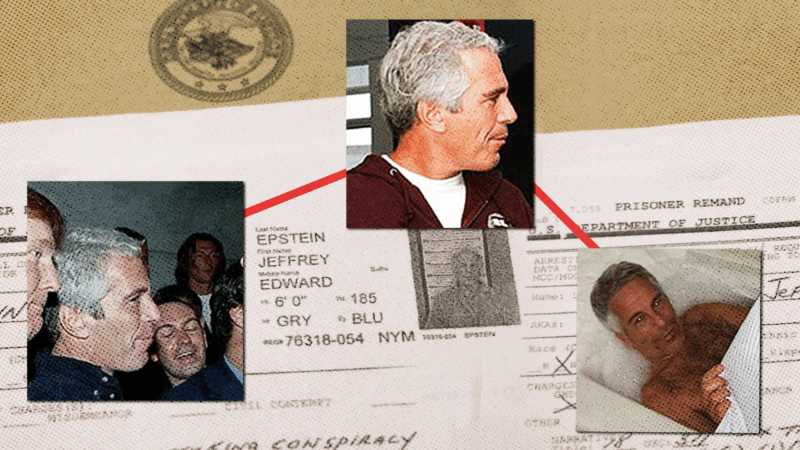

To make sense of the Justice Department’s latest documents, you have to understand what they actually are.

My name is in the Epstein files. How could that be? When the FBI received its first tip about the businessman molesting teenage girls, I hadn't even been born yet. The first time I heard the name "Jeffrey Epstein" was as a confused college student in 2015, watching feminist classmates protest a talk by Epstein's defense lawyer.

But search my name in the Justice Department's Epstein Library, and there it is, linked to a PDF file. Did I travel back in time? Was I hypnotized to forget my involvement in the most infamous sex abuse scandal in modern times? Do I happen to have an evil twin?

The less scintillating explanation: The FBI was reading my articles. What caught their eye wasn't even Reason's coverage of the Epstein case, to which I extensively contributed. Instead, one of my articles about the feds surveilling a science fiction author in the 1980s ended up in an FBI compilation of news coverage about the bureau. That compilation also includes an article about Epstein, so it ended up in the case files, which the Justice Department released last week under the Epstein Files Transparency Act.

I have always supported more transparency on the Epstein files. At its core, the scandal is about a politically well-connected man evading justice. And as I discovered last year while looking through the first batch of Epstein's leaked emails, those connections held the key to understanding a lot of political stories unrelated to his sex crimes.

Yet the reckless way some people are treating the Epstein files takes away from the value of disclosure. Tabloids have treated various unsubstantiated reports in the files as gospel truth. One man called the FBI claiming to have witnessed the ritualistic sacrifice of babies involving one former and one future U.S. president, only for FBI agents to conclude that his timeline made no sense. Worse yet, some commentators have been treating any appearance of someone's name in any context as a lurid story.

Last year, after the Justice Department released a smaller batch of files, users at the prediction site Polymarket took bets on which celebrity's name would appear. The comedian Stephen Colbert, it turns out, was mentioned in an email newsletter found in Epstein's inbox, and users rushed to put money on his name before the bet closed. As the odds shot up, Polymarket's official account tweeted out, "Stephen Colbert now the #1 suspect in the Epstein Files." Misleading, to say the least.

The sole member of Congress to vote against opening the files, Rep. Clay Higgins (R–La.), warned that the Epstein Files Transparency Act, as written, would "absolutely result in innocent people being hurt." Even though I still believe that the benefits of transparency outweigh the drawbacks, Higgins was onto something.

The files released by the Justice Department last week include evidence in the FBI's possession, internal government communications about the case, and the contents of Epstein's email inbox, all spread out across different "data sets" with no explanation. In other words, they include direct evidence of what Epstein did, what he told other people, and what other people said about him.

This evidence takes time and effort to put together into coherent narratives. (A group of volunteer programmers is helpfully collecting Epstein's emails and photos into a more user-friendly interface called Jmail.) Sleuths have uncovered a few allegations by confirmed Epstein victims against additional men, anonymous tips with more fantastical claims, distasteful comments from Epstein's associates excusing his behavior or asking to be invited to "the wildest party on your island," and political intrigue unrelated to sexual abuse, amid a mountain of spam.

But the public has been primed to look for a single "client list," detailing all of the men who participated in Epstein's sex crimes, potentially kept for blackmail. The idea that this list exists may have come from the earlier leaks of Epstein's address book and private jet flight logs. Although it is possible that Epstein was extorting people, the nature of the evidence highlights exactly why a "client list" probably doesn't exist.

Epstein's inbox includes a draft of a blackmail letter from Epstein to businessman Bill Gates concerning Gates' alleged activities with consenting adults—which Gates himself denies—and an email from Epstein asking a Russian cabinet minister about an adult sex worker "attempting to blackmail a group of powerful biznessman [sic] in New York." These are ad hoc attempts at using rumors and innuendo as leverage, not an organized conspiracy with membership dues for pedophiles.

To borrow a Soviet turn of phrase, Epstein was a blatnik. The term refers to using "personal networks for obtaining goods and services in short supply and for circumventing formal procedures," according to Matthew Stoller, a researcher at the American Economic Liberties Project, who argues that Epstein fulfilled a similar function for modern "superelites" operating outside the rule of law. From America to the Middle East, Epstein was constantly trading in political leverage, business opportunities, and personal favors.

Or as international relations professor Seva Gunitsky put it, Epstein was a "node" in the "sphere of elite impunity where American consultants, Russian oligarchs, Saudi princes, European politicians, Israeli intelligence figures and British ex-spies all swim in the same waters."

The reception of this news around the world has sometimes been surprising. While American talk show host Tucker Carlson points to Epstein's relationship with former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak to say that Epstein was an Israeli spy, current Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu uses that same relationship as evidence that his political rival Barak is tainted with pedophilia.

All speculations and open questions aside, the Epstein case is a story about political connections corrupting justice. The record shows that people around Epstein were willing to turn a blind eye to obviously unsavory activities (or help rehabilitate his reputation afterwards) in exchange for access to power. And part of what allowed them to turn a blind eye was treating rape as a cheeky punchline—as some Epstein files voyeurs are doing today.

To properly grasp the Epstein case, you have to take it seriously.