The U.N. Has Been Holding Climate Conferences for 30 Years. Carbon Emissions Continue To Climb.

Atmospheric carbon dioxide and global temperatures are on the rise after 33 years of largely fruitless negotiations.

United Nations' climate change conferences are exercises in futility. That is becoming ever clearer as the 30th conference of the parties (COP30) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) opens in Belém, Brazil. The chief goal of the UNFCCC is to achieve the "stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system."

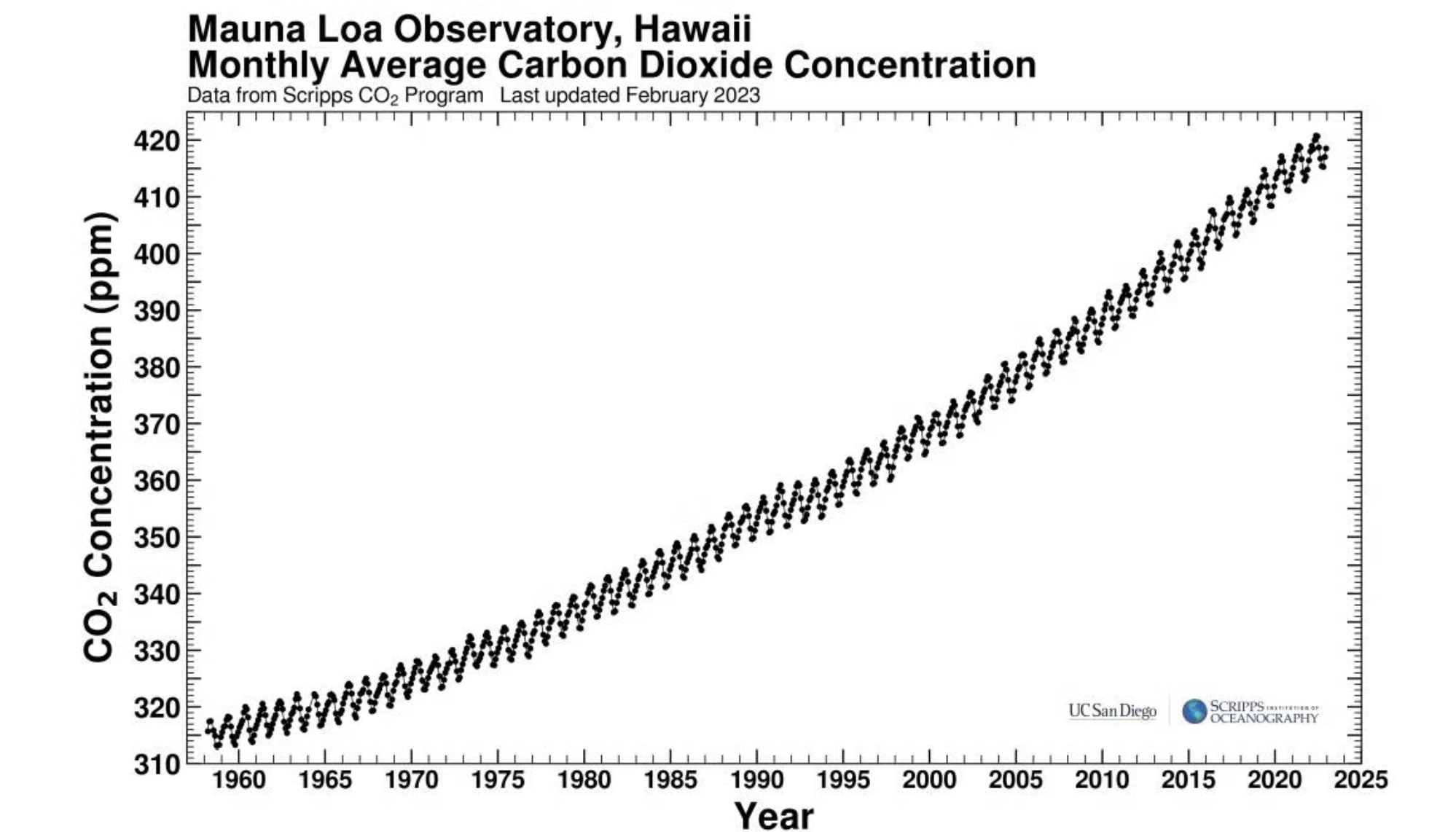

Since the UNFCCC was negotiated at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the concentration of greenhouse warming carbon dioxide (CO2) in the global atmosphere has been anything but close to stabilized. Instead, it has increased from 359 parts per million (ppm) to 425 ppm this year. And the increase is speeding up. The World Meteorological Organization reports that from 2023 to 2024, the global average concentration of CO2 "surged by 3.5 ppm, the largest increase since modern measurements started in 1957." The increase is largely the result of rising emissions from burning oil, natural gas, and coal to produce the energy that drives economic growth.

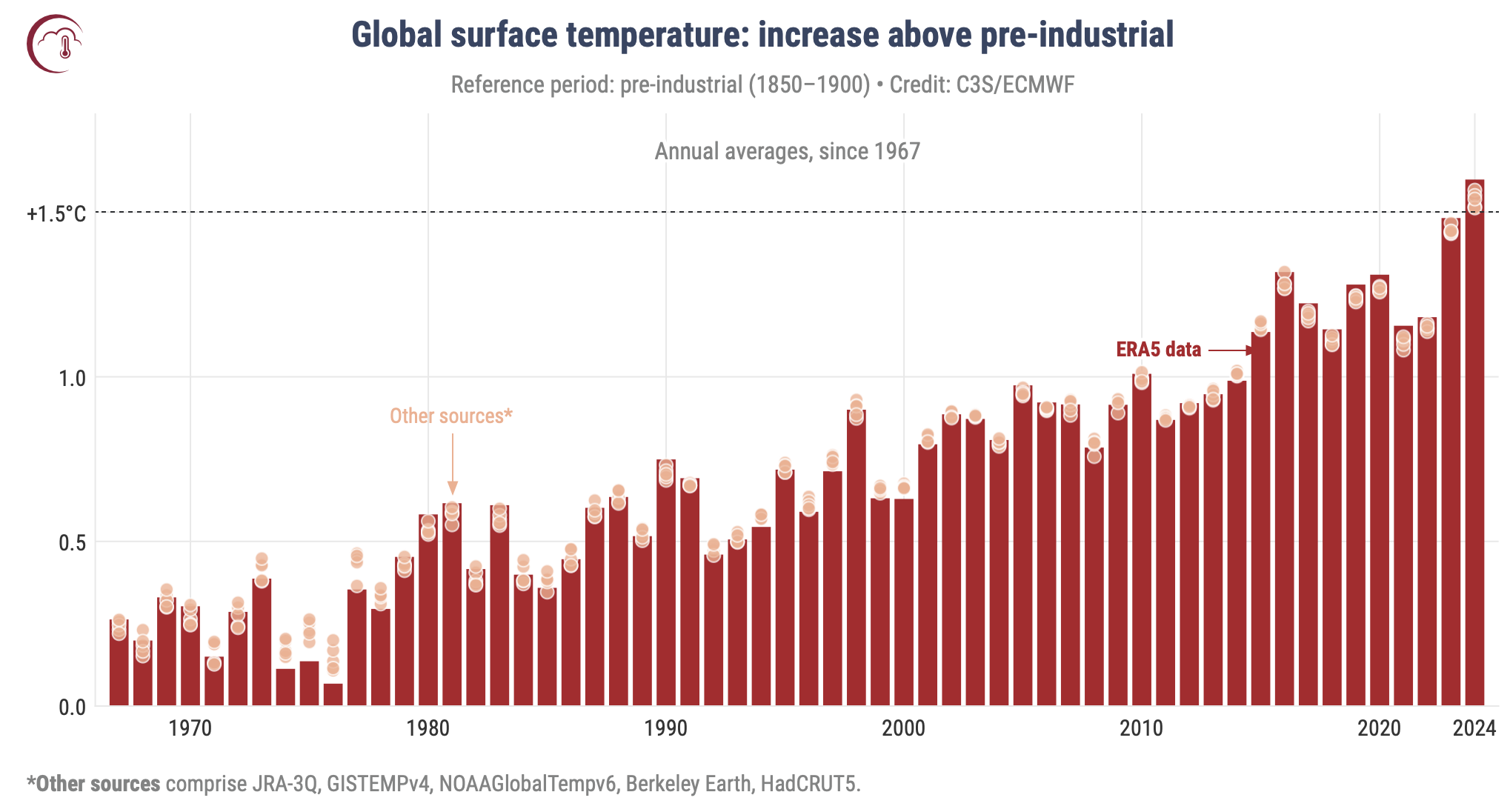

Global average temperatures have been rising concomitant with the increase in atmospheric CO2. In 1992, the global average temperature was about 0.5 degrees Celsius (0.9 degrees Fahrenheit) above the 1850–1900 baseline. In the succeeding 32 years, the global average temperature has risen, reaching 1.55 degrees Celsius (2.8 degrees Fahrenheit) above the baseline in 2024. In fact, 2024 was the hottest year in the instrumental record, and the last 10 years have been the 10 warmest years on record.

The signatories to the 2015 Paris Climate Change Agreement pledged to hold "the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels." That's not going to happen.

Climate researcher Zeke Hausfather asserted last year at COP29 that the 1.5 degree limit was "deader than a doornail." In June, Le Monde reported that a team of international climate scientists concurred that the goal "is no longer attainable." A recent U.N. report seems to affirm the unlikelihood of hitting these thresholds, finding that by 2035 humanity must cut its carbon dioxide emissions by 55 percent below its 2019 levels to achieve the global temperature limits outlined in the Paris Agreement. (I reported in 2022 from COP27 in Egypt that "1.5°C is already dead.")

At COP30, the Paris Agreement signatories are supposedly obligated to increase their nationally determined contribution pledges to cut their greenhouse gas emissions. But at the opening of COP30, around 130 out of 194 signatory countries had not yet submitted any new emissions reduction commitments. The U.N. report calculates that the pledges that have been made would cut global emissions by only 10 percent by 2035. So yes, the aspirational 1.5 degree limit is kaput.

So why have more than three decades of international negotiations largely failed? Because they have run headlong into what political scientist Roger Pielke, Jr. calls the "iron law of climate policy." As Pielke puts it, "when policies focused on economic growth confront policies focused on emissions reductions, it is economic growth that will win out every time."

In their October 2025 article in Communications Earth & Environment, a team of researchers at the University of Washington more or less confirmed Pielke's law. The researchers note that "overall carbon emissions rose, due to the rapid rise in world GDP, which more than canceled out the progress" made in reducing emissions. On the other hand, they report the good news that carbon intensity—carbon emissions per unit of GDP—has been steadily declining. Basically, markets are encouraging the adoption of low-carbon energy technologies and ever greater fuel efficiency. The researchers calculate that if carbon intensity continues to improve at current rates that global emissions will fall by 64 percent by 2100. That implies a projected increase in global average temperature of 2.4 degrees Celsius by 2100 and basically rules out the worst-case climate change scenarios.

On Thursday, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres denounced missing the 1.5 degree limit as a "moral failure" and declared, "This COP must ignite a decade of acceleration and delivery." More than three decades of largely fruitless climate negotiations argue that COP30 will prove to be just more of the same.