Zach Cregger's Weapons Is a Horror Film That Doesn't Tell You What To Think

A twisted, terrifying follow-up from the director of Barbarian

I can't tell you too much about Weapons, Zach Cregger's electric follow-up to the surprise horror hit Barbarian. But I can say that it's a movie about a classroom full of children who all disappear. And it's called Weapons. What does that bring to mind?

School shootings, yes, and that might be part of what Cregger is ultimately getting at. It's plausible, I suppose, with some creative interpretation. But it's certainly not a foregone conclusion. I can think of other possible interpretations—involving COVID-19, perhaps, or the unseemly use of children as political props in adult grievances, or the general failure of adult authority figures to protect and shield kids from the horrors of a world full of madness and evil. But it isn't obviously about any of these things. It's a movie that refuses to be straightforwardly interpreted in some headline-ready format. Thank goodness.

Weapons isn't what critics sometimes call a "potent metaphor," which usually means an "obvious metaphor." There's no signposting, no speechifying, no theme-is-stated moment that tells you what it all means. There's just a sequence of strange and terrifying events, maddeningly difficult to explain until you've seen the film through to the very end, and even then it remains hauntingly impenetrable. Unlike so many of today's supposedly elevated horror films, there's no one clear concept connecting all the dots to some modern social problem. I can tell you what happens in Weapons, but not precisely what it's supposed to mean.

Which is part of what makes it so entrancing, and so terrifying. Over a black screen, a child's voice explains that one night, in a small town, every child in a single elementary school classroom got up and left their homes at 2:17 in the morning. Every child—except for one. Security camera footage shows the other kids fleeing their homes in a strange, wing-like pose, tearing off into the darkness. And then they just vanish.

What happened to those children? Why did they all get up and run from their homes? Why was one spared this mysterious fate?

As with Barbarian, which kicked off with an easy-to-grasp Airbnb mix-up and then went places you'd never expect, Weapons isn't the sort of movie where you can guess the ending, or even the general shape of the story, from the setup. Cregger tells the story in a series of looping, overlapping, non-linear chapters, like a Quentin Tarantino movie, each one centered on a character who plays some important part in the story.

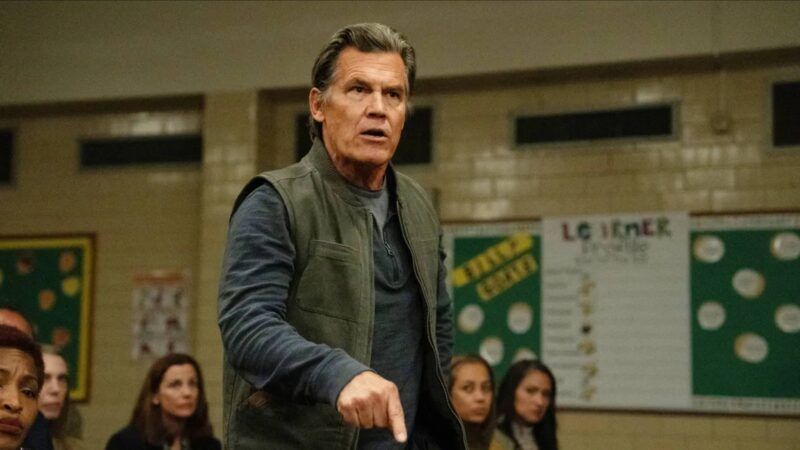

To the extent that there's a central character, it's Justine Gandy (Julia Garner), the teacher whose class full of kids disappeared. Gandy has a troubled past and makes some questionable decisions, but she also seems rather clearly determined to help find the missing kids. But before her story can take over the movie, the focus shifts to Archer (Josh Brolin), the father of one of her students. He, too, has become obsessed, in his grief, with solving the mystery of their disappearance, but he doesn't even know what kind of mystery it is. At a community meeting, he stands up and yells about how angry he is because of how inexplicable it is. More than anything, he wants answers, certainty, something solid to hold on to in the absence of his son.

There are other characters in focus too: a local cop with connections to Justine, an addict who happens to be in the wrong place at several wrong times, the school principal struggling to work within the bureaucratized world of public education, and, eventually, the one child who was spared. They're all victims, all affected by the events, but none of them are purely sympathetic types. These aren't the winning, likable, "rootable" protagonists that Hollywood typically insists on, but rather complex people with real flaws and difficulties.

There's no hero in Weapons, no one to save the day at the end. Rather, it's a compound tragedy about the terrifying mystery of existence. The scary thing isn't what it all means, but that its meaning refuses to present itself in some easy-to-understand form, even, and perhaps especially, after all is revealed. It doesn't tell you what it means or what to think. The real horror is not knowing.