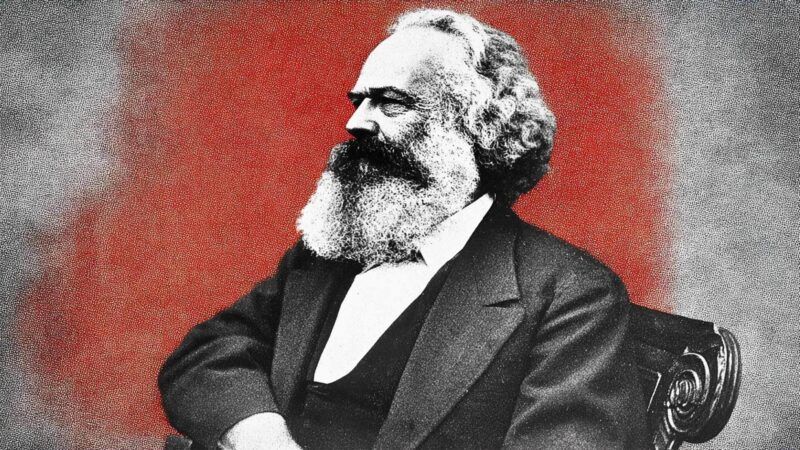

A Free Speech Lesson From Karl Marx

Censorship tends to blow up in the faces of the censors.

There's a basic principle of free speech that the censors always seem to forget. Namely, the act of suppressing speech only tends to add more fuel to the speaker's fire.

Don't believe me? Just ask Karl Marx.

You’re reading Injustice System from Damon Root and Reason. Get more of Damon’s commentary on constitutional law and American history.

In 1842, Marx was an up-and-coming radical journalist and chief editor at a Prussian publication called the Rheinische Zeitung. His readers thrilled to his biting pen and caustic attacks on the Prussian monarchy. But when Russian Emperor Nicholas I happened to read one of Marx's articles, which also savaged Prussia's then-key ally, Russia, the boot of censorship came stomping down. Russia lodged an official complaint about Marx's writings with the Prussian regime and the Rheinische Zeitung was repressed by state censors in 1843.

"I am tired of this hypocrisy and stupidity, of the boorishness of officials, I am tired of having to bow and scrape and invent safe and harmless phrases," Marx told a correspondent. "In Germany there is nothing I can do." So Marx departed for Paris and the rest, as they say, is history.

"Two years later," the political philosopher Isiah Berlin wrote in his illuminating 1939 biography, Karl Marx: His Life and Environment, Marx "was known to the police of many lands as an uncompromising revolutionary communist, an opponent of reformist liberalism, the notorious leader of a subversive movement with international ramifications." Indeed, Berlin argued, "the years 1843-5 are the most decisive of his life." It was during that tumultuous period in which Marx truly became the notorious figure that we recognize today.

All of which suggests an interesting counterfactual: What if the Prussian authorities had left Marx in peace to crank out his rancorous articles? Might he have remained content to scribble away and never become the communist firebrand of historical infamy? What if?

But the censors did not leave Marx alone. They hounded him out of Germany. And their efforts backfired spectacularly. Not only did the censors fail to throttle Marx's work; they actually turbo-charged his radicalization and greatly furthered the spread of his ideas.

The historical record is replete with similar stories about ultimately doomed efforts to silence political speech. For example, when I was researching my book about Frederick Douglass and the Constitution some years ago, I was struck by how many celebrated antislavery activists first became radicalized against slavery when they witnessed proslavery mobs trying to stamp out abolitionist speech.

Take the case of the great Salmon P. Chase. In the summer of 1836, Chase was a successful young lawyer living in Cincinnati, Ohio. On July 12, a proslavery mob forced its way into the offices of a local abolitionist newspaper called the Philanthropist and destroyed the printing press. Two weeks later, the mob went hunting for the paper's editor, the abolitionist James G. Birney.

"I heard with disgust and horror the mob violence directed against the Anti-Slavery Press and Anti-Slavery men of Cincinnati in 1836," Chase later wrote. "I was opposed at this time to the views of the abolitionists, but I now recognized the slave power as the great enemy of freedom of speech [and] freedom of the press and freedom of the person. I took an open part against the mob."

So began Chase's extraordinary antislavery career, which included arguing against the Fugitive Slave Act before the U.S. Supreme Court, helping found the antislavery Free Soil Party (whose catchy motto, "Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, and Free Men," he coined), and eventually replacing the hated Roger Taney, author of the disgraceful Dred Scott decision, as chief justice of the United States.

It all started with Chase's outrage at the sight of proslavery thugs on the rampage against abolitionist speech. "From this time on," Chase recalled of the violent summer of 1836, "I became a decided opponent of Slavery and the Slave Power."

I suppose that's the one good thing that might be said about censorship: It has a pronounced tendency to blow up in the faces of the censors.