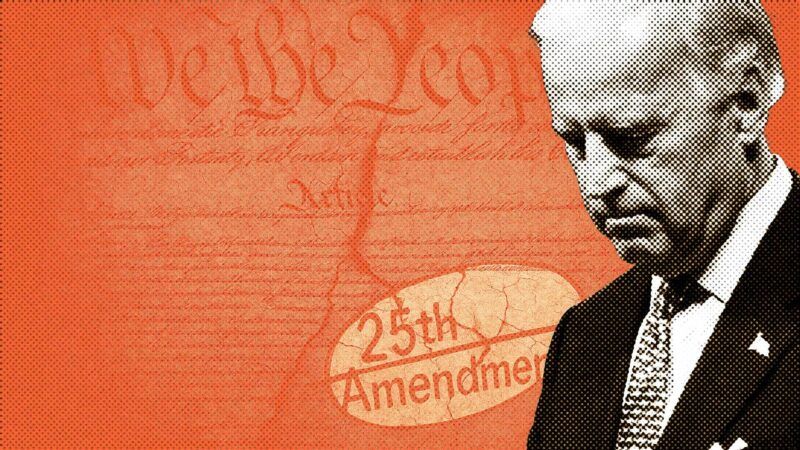

Have Presidents Grown Too Powerful To Be Removed From Office?

Joe Biden showed that the 25th Amendment doesn't work. Donald Trump showed that impeachment is broken too.

The cover-up of President Joe Biden's cognitive decline is a scandal "maybe worse than Watergate," CNN's Jake Tapper opined recently. In this case, the key question is: "What didn't the president know and when didn't he know it?"

Last week the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee ramped up its efforts to answer these questions. Citing Tapper and Alex Thompson's book, Original Sin: President Biden's Decline, Its Cover-Up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again, The committee's chairman, Rep. James Comer (R–Tenn.), issued demand letters to five senior Biden aides and subpoenaed the White House doctor who certified that the president was fit for duty.

He clearly wasn't. Even in 2020, Biden struggled to feign lucidity in tightly scripted Zoom town halls. "He couldn't follow the conversation at all," said top Democrats who saw the raw footage; it "was like watching Grandpa who shouldn't be driving." The four Cabinet members who spoke with Tapper and Thompson described equally scripted Cabinet meetings with a president incapable of answering pre-screened questions without the aid of a teleprompter. One recounted being "shocked by how the president was acting" at a 2024 meeting: "'disoriented' and 'out of it,' his mouth agape." One campaign adviser asked himself after a post-debate conversation with Biden: "What are we doing here? This guy can't form a fucking sentence."

Put more politely, the president was "unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office"—just cause for removal. "This is why we have the 25th Amendment," Sen. Josh Hawley (R–Mo.) said recently, "it's clear now that it probably should have been invoked from the beginning."

That key players instead propped up a semiconscious figurehead, hoping to gaslight their way to reelection, isn't just a scandal—it's a constitutional failure. That failure reveals an uncomfortable truth: As the presidency has grown ever more powerful, even manifestly unfit presidents have become nearly impossible to remove.

'We Dare Not Let That Happen Again'

Ratified in 1967, the 25th Amendment provides two ways the vice president can get the keys from a nonfunctioning president. Under Section 3, the president hands them over voluntarily; under Section 4, the VP can take them away when he or she and a majority of the Cabinet determine that the president is incapacitated.

Section 4 was meant to cover cases of "mental debility," as one of the amendment's architects, Rep. Richard Poff (R–Va.), explained, where the president "is unable or unwilling to make any rational decision…particularly the decision to stand aside." Top of mind was avoiding a replay of the Woodrow Wilson debacle. Leveled by a pair of strokes in 1919, the 28th president spent the remainder of his term bedridden and incommunicado while first lady Edith Wilson essentially ran the executive branch of the government. "We dare not let that happen again," Rep. Emanuel Celler (D–N.Y.) warned during the House debate over the 25th amendment.

Yet it arguably just did. In the six-decade life of the amendment, Biden's presidency is as close as we've come to the paradigmatic Woodrow Wilson case, complete with a latter-day Edith Wilson—Jill Biden—and a clique of advisers the Biden staff dubbed "the Politburo."

The Politburo and the Autopen

An inert president may sound like a libertarian dream. Alas, it's not as if nothing gets done while he's checked out. The New York Times calls concerns about heavy use of the autopen a "conspiracy theory." But if reports from the Heritage Foundation's Oversight Project are accurate, it's at least interesting that, from mid-July 2022 on, most executive orders issued by the administration were signed remotely, even when Biden was in Washington.

Despite the Politburo's efforts to conceal the president's decline, the Cabinet knew. At any point, the vice president and eight Cabinet-level "principal officers" could have moved to replace him via Section 4. Why didn't they?

For one thing, the 25th Amendment's "eject button" is almost impossible to trigger: Even broaching the possibility risks crashing the plane. Any single Cabinet member who disagrees could "short-circuit the process by informing the President, potentially triggering a cascade of firings." (Something similar happened in 1920, when Wilson's secretary of state, Robert Lansing, was forced out for suggesting a transfer of power to Vice President Thomas Marshall.) Another problem is that even with the support of the Cabinet, it was unclear whether Vice President Harris could garner enough GOP votes in Congress to ratify the switch. Without a supermajority of both Houses, Biden would come back from time-out and the firing frenzy would begin.

'Too Big to Fire'

According to Tapper and Thompson, the 25th Amendment solution was never even considered. Instead, the Politburo's reigning calculus was that Biden "just had to win and then he could disappear for four years—he'd only have to show proof of life every once in a while." Meanwhile, the same people hoping to defraud the electorate subjected the rest of us to lectures about threats to "our democracy."

Worse still, it isn't just the 25th Amendment that's broken. The Constitution provides another method for ejecting an unfit president before his term is up: the impeachment process. In the last five years, we've pressure-tested both failsafe mechanisms. Neither one worked.

In his first term, President Donald Trump was impeached twice, the second time for provoking a riot while trying to intimidate Congress and his own vice president into overturning the results of an election he lost. Even that enormity didn't earn him conviction and disqualification in the Senate trial.

The fact that we've never managed to eject a sitting president via the impeachment process suggests that the framers set the bar for removal—conviction by two-thirds of the Senate—too high. For Section 4 of the 25th Amendment, which requires a supermajority of both houses, the bar is even higher.

Lowering the bar to an impeachment conviction—say, to 60 votes—would better protect the public from an abusive president. It would also provide security against a future Biden/Wilson scenario. Though impeachment aims primarily at abuse of power, it was designed as a remedy for presidential unfitness generally: "defending the community against the incapacity, negligence, or perfidy of the Chief Magistrate," as James Madison put it. Properly understood, that covers cases of "mental debility."

If You Can't Fire Him, Shrink the Job

Of course, that reform faces a dauntingly high bar of its own: It would take a constitutional amendment, the prospects for which are dim.

But making presidents easier to fire is only one way to tackle our fundamental problem; the other is to shrink the job. "Incapacity, negligence, and perfidy" in the presidency are bigger threats than ever, because presidents now have the power to reshape vast swaths of American life. They enjoy broad authority to decide what kind of car you can drive, who gets to use which locker room, who is allowed to come to the United States, and whether or not we have a trade war with China—or a hot war with Iran. That's more power than any one fallible human being should have.

Making the presidency safe for democracy will require a reform effort on the scale of the post-Watergate Congresses: reining in emergency powers, war powers, the president's authority over international trade, and his ability to make law with the stroke of a pen. It's a heavy lift, but worth the effort. If we're worried about the damage unfit presidents can do, we should give them fewer things to break.