The Originalist Debate About Affirmative Action

The Supreme Court grapples with the original meaning of the 14th Amendment in Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina.

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments last month in Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina, which asks whether state colleges and universities should be prohibited from using race as a factor in determining admissions. Under Supreme Court precedent, when the government (including a state university) takes race into account, the government's actions are subject to "strict scrutiny," the most searching form of judicial review. To satisfy strict scrutiny review, the government must show, first, that its actions serve a "compelling interest," and, second, that its actions are "narrowly tailored" to achieve that interest. Strict scrutiny is typically a high judicial hurdle to clear.

But there was another big question lurking around the perimeter of the case. Namely, does the original meaning of the 14th Amendment—which says that no state may "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws"—allow or disallow affirmative action in higher ed admissions?

Standing on one side of that debate is Justice Clarence Thomas, who has long maintained that "the Equal Protection Clause strips States of all authority to use race as a factor in providing education." "All applicants must be treated equally under the law," Thomas wrote in Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin (2013), "and no benefit in the eye of the beholder can justify racial discrimination."

On the other side is a friend of the court brief filed in support of the University of North Carolina by a group of historians and legal scholars, including self-described originalists, who maintain that "nothing in the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment…clearly prohibits race-conscious admissions policies. Rather, as demonstrated by the Fourteenth Amendment's text and historical context, the Reconstruction Framers understood the Amendment to bar States from enacting and enforcing laws that subordinated people based on race and to permit as constitutional actions designed to ameliorate the conditions of members of a subordinated race."

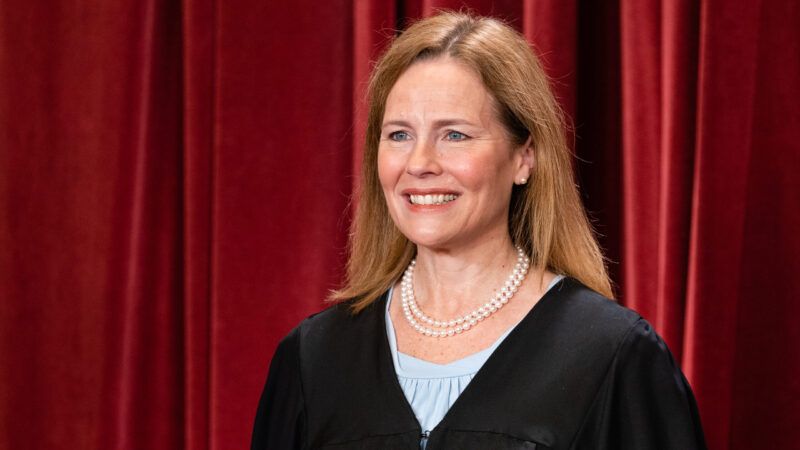

Regrettably, that originalist debate did not get much airtime during last month's oral arguments, But it did pop up in one notable exchange. Shortly after Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar positively invoked the historians' brief, Justice Amy Coney Barrett told her, "I agree with you, when you look at the originalist evidence…that some race-conscious measures were permitted at least in a remedial sense, right? Desegregation is an example of that." But, asked Barrett, how does that history affect modern strict scrutiny review? "If you were writing on a blank slate, would you say that university affirmative action programs don't implicate the Fourteenth Amendment? Or are you saying that they just very plainly would satisfy our modern tiers of scrutiny because the interest is compelling?"

Prelogar conceded that "because they involve racial classifications," the admissions programs should face strict scrutiny. "We're not suggesting that under an originalist case, they would just be automatically exempt."

It was a notable exchange for a few reasons. For one, Barrett seemed at least possibly open to the idea that the originalist evidence in this case cuts in favor of affirmative action. At the same time, however, Barrett extracted from Prelogar the concession that, in the government's view, the originalist evidence was not dispositive for the ultimate outcome of the case. In other words, even with history on its side, the school's admission program should still face heightened judicial review, which means that Barrett could still vote against the program on strict scrutiny grounds, even in the face of originalist evidence that supports the program.