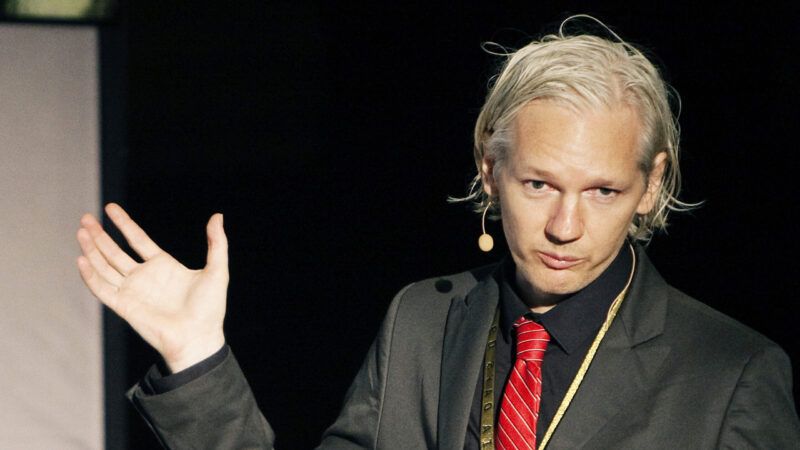

Julian Assange Extradition Decision the Latest Blow to Freedom of the Press

Either everybody gets to enjoy journalistic freedom, or it will turn into glorified public relations work for the powers-that-be.

With the decision by Britain's High Court that Julian Assange can be extradited to the United States, his high-profile case appears, at long last, to be coming to some sort of unfortunate end. Assange's fate will soon be in the hands of the U.S. federal courts, and it seems unlikely that either he or freedom of the press will emerge unscathed from the ordeal.

In a decision that heavily relies on the British government's history of believing official U.S. assurances, the High Court took on face value American claims that Assange will not be held in especially restrictive prison conditions "unless he were to do something subsequent to the offering of these assurances" that would justify such treatment. As a result, the court ordered the district judge to "send the case to the Secretary of State, who will decide whether Mr Assange should be extradited to the USA." That's pretty much a given, since it's what the governments of both the U.K. and the U.S. sought all along.

The charges Assange will face in the United States relate to his "alleged role in one of the largest compromises of classified information in the history of the United States," in the words of the U.S. Department of Justice. Basically, Wikileaks worked with Chelsea Manning to reveal information that embarrassed the United States government, and Assange faces espionage charges over the means used to acquire the data.

Ironically, Assange faces extradition to the U.S. in a year in which the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov for defying the governments of, respectively, the Philippines and Russia to report news that officials find inconvenient.

"They are representatives of all journalists who stand up for this ideal in a world in which democracy and freedom of the press face increasingly adverse conditions," the Norwegian Nobel Committee noted. "Free, independent and fact-based journalism serves to protect against abuse of power, lies and war propaganda," it added.

Notably, the information that Assange and Manning exposed was primarily about U.S. military operations, revealing facts that, arguably, contradict war propaganda.

"The US government's indictment poses a grave threat to press freedom both in the United States and abroad," Amnesty International objected to the U.K. High Court decision. "If upheld, it would undermine the key role of journalists and publishers in scrutinizing governments and exposing their misdeeds would leave journalists everywhere looking over their shoulders."

"Today's ruling is an alarming setback for press freedom in the United States and around the world, and represents a notable escalation in the use of the Espionage Act in the 'War on Whistleblowers' that has expanded through the past several presidential administrations," the Freedom of the Press Foundation commented.

"This has served the purpose of illuminating all of the global voices of freedom to the authorities. 'If this can happen to Assange for simply exposing the truth, then it could happen to me for publishing a leaked document,'" Richard Hillgrove, Julian Assange's former PR representative, says over email. "At the same time, it's created a petrifying and chilling example to the global journalistic community – crushing investigative journalism worldwide."

That said, support for Assange isn't universal among journalists.

"I think that the wholesale dumping of Wikileaks actually isn't journalism," Maria Ressa, one of this year's Nobel Peace Prize winners, insisted in 2019. "A journalist sifts through, decides, and knows when something is of value to national security and withholds until you can verify that it isn't."

But as Reason's Jacob Sullum pointed out last month, journalists tend to get unreasonably sniffy about their profession, insisting that it's an elevated status rather than an activity that anybody can do.

"As UCLA law professor and First Amendment scholar Eugene Volokh has shown, the idea that freedom of the press is a privilege enjoyed only by bona fide journalists, however that category is defined, is ahistorical and fundamentally mistaken," Sullum wrote. "It is clear from the historical record that 'freedom of the press' refers to a technology of mass communication, not to a particular profession."

That is, anybody gathering information and releasing it to the public is engaged in journalism, even if others doing the same thing have different ideas about how that information should be acquired and what should be reported. And, while government officials habitually evoke "national security" as a talismanic phrase to ward off scrutiny, there's no convincing reason why the use of those words by themselves should prevent publication of Manning's information, the Pentagon Papers, or anything else.

Speaking of the Pentagon Papers, consider this.

"This is the first indictment of a journalist and editor or publisher, Julian Assange," Daniel Ellsberg, who released the documents that came to be known as the Pentagon Papers, pointed out in 2019. "I see on the indictment, which I've just read, that one of the charges is that he encouraged Chelsea Manning and Bradley Manning to give him documents, more documents, after she had already given him hundreds of thousands of files. Well, if that's a crime, then journalism is a crime, because just on countless occasions I have been harassed by journalists for documents, or for more documents than I had yet given them."

Of course, journalism won't be openly classified as a crime in Assange's case or any others likely to arise in the near future. But his years-long ordeal, culminating recently in the High Court decision and a simultaneous stress-induced mini-stroke (according to his fiancee, Stella Moris), is a hell of a shot across the bow to those engaged in newsgathering. That the shot comes from the governments of nominally free countries only emphasizes the message. What treatment can those exposing the abuses and missteps of the powers-that-be expect from overt authoritarians when British and American officials applaud the punishment of inconvenient reporting?

In the end, if we're going to preserve press freedom and larger protections for free speech, professional journalists need to stop pretending that what they do requires membership in an exclusive club. Either Julian Assange and everybody else get to practice journalism in ways that offend people in power, or it will get turned into glorified public relations work for those who hold power.