50 Years After Attica, Prisons Are Still the Problem No One Wants To See

The men of Attica said they had "set forth to change forever the ruthless brutalization" of U.S. prisoners. For all the horror and bloodshed, not much has changed.

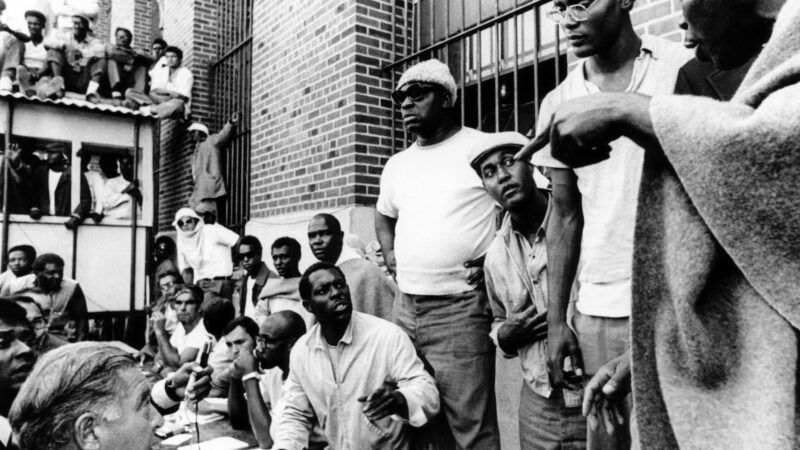

On September 9, 1971, Elliott "L.D." Barkley stepped forward to speak on behalf of the 1,281 inmates who had seized control that day of Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York. Reading the statement of his fellow incarcerated men, Barkley said that they had "set forth to change forever the ruthless brutalization and disregard for the lives of the prisoners here and throughout the United States."

During the initial chaos of the revolt, which started in a confused panic rather than a well-planned mutiny, a mob of incarcerated men fatally injured one of the guards and took 39 other prison staffers hostage. Some of the Attica inmates' demands were impossible for state officials to swallow, such as amnesty from prosecution and the resignation of the warden, but most of the rest were related to the atrocious medical care, political and religious repression, and racism that had led to years of rising tensions inside the prison.

Four days later, and 50 years ago today, as negotiations floundered and the Attica inmates took eight hostages onto a catwalk at knifepoint, roughly 550 New York law enforcement officers retook the prison by force, firing wide-arc buckshot indiscriminately into a fog of tear gas. "The bullets were coming like rain," one hostage remembered. The officers killed 29 Attica inmates and 10 hostages.

This was part of a string of violent episodes in U.S. prisons in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Several weeks prior, black radical George Jackson was killed during an armed escape attempt in California, leading to a hunger strike at Attica. A year after Attica, inmates at the D.C. jail—a century-old building that the American Civil Liberties Union described as "a filthy example of man's inhumanity to man"—took 12 staffers hostage.

But Attica was the bloodiest, most dramatic event in the history of U.S. prisons, and it has been lodged in the American consciousness, potent and divisive, ever since. Even the language surrounding the event is fraught. For example, whether to call it a "riot." Heather Ann Thompson's Blood in the Water, a masterful history of the incident and the decades-long state cover-up that ensued, calls it the "Attica uprising."

What's beyond dispute or semantic arguments, though, is that the state of New York tried to hide the fact that state troopers killed 10 hostages and tortured the surviving inmates in the aftermath.

Government officials initially claimed that the hostages' throats had been slit, a lie that major news outlets dutifully repeated. The local forensic examiner was pressured to alter his findings that the hostages been shot. His refusal to do so led to professional retaliation, death threats, intimidation from law enforcement, and claims that he was a radical leftist. (In reality, he'd voted for Richard Nixon.) State troopers even visited funeral homes to try to pressure morticians into claiming the bodies had no bullet holes.

The state government then worked for decades to hide and destroy evidence of wanton violence and retaliation, and to undermine lawsuits not only by Attica inmates but by the families of hostages who were killed. It sent measly worker's compensation checks to slain hostages' widows, knowing full well that if they cashed the checks, it would bar them from bringing civil lawsuits in the future.

Conditions at Attica and other U.S. prisons improved somewhat after the massacre. The New York Times reported a year later that most of the Attica rebellion's demands had been met. On a broader scale, federal judges in the 1970s and '80s began to exercise more oversight over decrepit prisons. But those new programs and privileges disappeared again in the "tough on crime" era.

And despite a Supreme Court ruling in 1976 finding that the Eighth Amendment prohibits "deliberate indifference" to incarcerated people's medical needs, the truth is that barbaric indifference is the fundamental quality of American prisons and jails, and neither the Supreme Court or all of the bloodshed and horror of Attica could change that.

Last year, I reported on several deaths due to alleged medical neglect at Aliceville Federal Correctional Institution, a federal women's prison in Alabama. While I was investigating that story, I came across the case of a woman incarcerated there who had been suffering from an untreated uterine fibroid that weighs roughly 15 pounds. She had been waiting in pain for outside treatment since an Aliceville physician first diagnosed the fibroid in 2016. According to a federal judge, the fibroid "causes 'visible protrusions' from [her] abdomen and causes her pain, uterine bleeding, anemia, infection, and fevers."

The last time I emailed with this woman, in July, she said she had still not received treatment.

Earlier this year, I received a letter from a woman incarcerated in Lowell Correctional Institution, a Florida state prison, asking for help in getting her 25-year mandatory minimum sentence for opioid trafficking reduced. She was 62 years old, and it was her first offense. She died while the letter was in transit. She'd had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other lung ailments that led to difficulty breathing, but she said she couldn't get any treatment.

Lowell is the same prison where guards broke the neck of a woman with mental illness, resulting in a $4.6 million lawsuit settlement. The Justice Department has since put Florida on notice that the conditions at Lowell are so bad that they violate the Constitution. Federal investigators found that "sexual abuse of women prisoners by Lowell corrections officers and staff is severe and prevalent throughout the prison." So far, the Florida Department of Corrections has denied and disputed the Justice Department's findings.

The Justice Department's Civil Rights Division also sued Alabama last year over its gore-soaked prison system, after issuing two reports detailing constitutional failures to protect inmates from violence and sexual assaults.

At Mississippi's infamous Parchman prison, ProPublica reports, the drinking water has violated the Safe Drinking Water Act dozens of times, and the Environmental Protection Agency has cited the prison's sewage system for three years for violating the Clean Water Act. The Justice Department has also launched an investigation into gruesome violence and wretched facilities in Mississippi prisons, following a string of deaths and years of deteriorating conditions.

In San Diego, video recently emerged in a lawsuit showing that a jail deputy watched an incarcerated woman on methamphetamines gouge out her own eyes, one by one, without intervening.

The Indiana chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union filed Eighth Amendment lawsuits today on behalf of three prison inmates who allege that they were forced to live in pitch-black isolation cells, where they were shocked by live wires hanging from broken lights. The men also say they were exposed to rain and snow by broken windows that were eventually covered in sheet metal.

Fifty years ago today, Elliott Barkley—21 years old and just days away from his release—was shot and killed. An autopsy report said he had been struck in the back and killed by a tumbling .270 slug, possibly a ricochet, during the retaking of Attica. But several witnesses, including New York state assemblyman Arthur Eve, said Barkley had been alive an hour after the inmates had surrendered.

Prisons are the problem no one wants to see. Fifty years after Attica, we seem to have buried the truth about them better than any ass-covering bureaucrat could have hoped for.