John Roberts Does Not Think California's Special Restrictions on Religious Services Discriminate Against Churches

As SCOTUS declines to issue an injunction, the chief justice says the state's COVID-19 control measures seem consistent with the First Amendment.

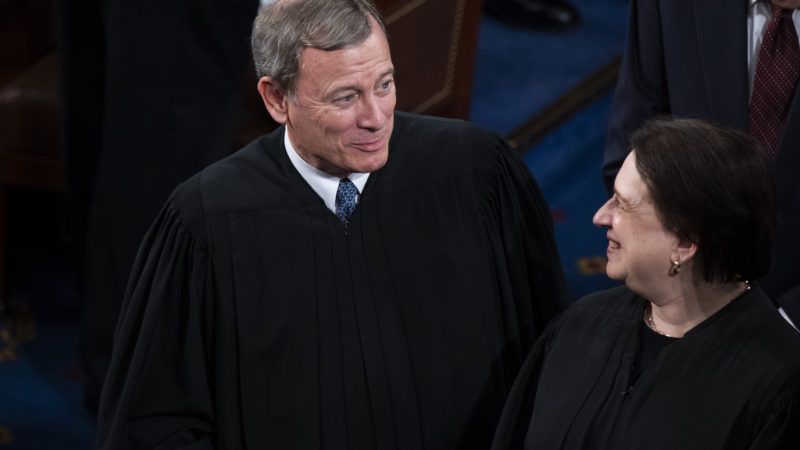

The Supreme Court last Friday rejected a Chula Vista church's request for an injunction against California's pandemic-inspired restrictions on religious services, an issue that has divided federal appeals courts. In a concurring opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts argues that the state's COVID-19 control measures seem to be consistent with the First Amendment's guarantee of religious freedom.

"Although California's guidelines place restrictions on places of worship, those restrictions appear consistent with the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment," Robert writes. "Similar or more severe restrictions apply to comparable secular gatherings, including lectures, concerts, movie showings, spectator sports, and theatrical performances, where large groups of people gather in close proximity for extended periods of time. And the Order exempts or treats more leniently only dissimilar activities, such as operating grocery stores, banks, and laundromats, in which people neither congregate in large groups nor remain in close proximity for extended periods."

Roberts emphasizes that states have broad authority to protect the public against communicable diseases. "Where those broad limits are not exceeded," he says, "they should not be subject to second-guessing by an 'unelected federal judiciary,' which lacks the background, competence, and expertise to assess public health and is not accountable to the people."

Four justices—Brett Kavanaugh, Neil Gorsuch, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito—disagreed with Roberts' analysis. In a dissenting opinion joined by Thomas and Gorsuch, Kavanaugh rejects Roberts' characterization of California's restrictions as neutral and generally applicable—the standard for avoiding strict scrutiny of policies that impede religious freedom.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom initially planned to let several types of businesses reopen while keeping houses of worship closed—a policy that provoked resistance from thousands of churches and a cautionary letter from the U.S. Department of Justice. On May 22, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit peremptorily rejected the South Bay United Pentecostal Church's motion for an injunction against Newsom's reopening plan. That decision inspired an 18-page dissent by Judge Daniel Collins, who said "there is no denying" that California's "amalgam of rules is the very antithesis of a 'generally applicable' prohibition." Newsom later revised his plan, saying houses of worship could reopen as long as they limited attendance at services to no more than 100 people and no more than 25 percent of capacity.

"The basic constitutional problem is that comparable secular businesses are not subject to a 25% occupancy cap, including factories, offices, supermarkets, restaurants, retail stores, pharmacies, shopping malls, pet grooming shops, bookstores, florists, hair salons, and cannabis dispensaries," Kavanaugh writes. He notes that South Bay United Pentecostal Church "is willing to abide by the State's rules that apply to comparable secular businesses, including the rules regarding social distancing and hygiene." But it "objects to a 25% occupancy cap that is imposed on religious worship services but not imposed on those comparable secular businesses."

Kavanaugh quotes repeatedly from a May 9 decision in which a unanimous 6th Circuit panel granted an injunction pending appeal to Maryville Baptist Church, which had challenged Kentucky Gov. Andrew Beshear's lockdown orders. "California undoubtedly has a compelling interest in combating the spread of COVID–19 and protecting the health of its citizens," Kavanaugh says. "But 'restrictions inexplicably applied to one group and exempted from another do little to further these goals and do much to burden religious freedom.' What California needs is a compelling justification for distinguishing between (i) religious worship services and (ii) the litany of other secular businesses that are not subject to an occupancy cap. California has not shown such a justification."

Quoting again from the 6th Circuit ruling, Kavanaugh asks: "Assuming all of the same precautions are taken, why can someone safely walk down a grocery store aisle but not a pew? And why can someone safely interact with a brave deliverywoman but not with a stoic minister?" He adds that "the State cannot 'assume the worst when people go to worship but assume the best when people go to work or go about the rest of their daily lives in permitted social settings.'" Without "a compelling justification (which the State has not offered)," he says, "the State may not take a looser approach with, say, supermarkets, restaurants, factories, and offices while imposing stricter requirements on places of worship."

As far as Kavanaugh and the other dissenters are concerned, it is clear that California is discriminating against religiously motivated conduct. "California's 25% occupancy cap on religious worship services indisputably discriminates against religion," he says, "and such discrimination violates the First Amendment."

Roberts, by contrast, echoes the position that a unanimous 7th Circuit panel took on May 16, when it declined to issue an injunction against restrictions on religious services in Illinois. The 7th Circuit said Illinois was treating churches the same as other settings that pose similar risks of virus transmission, such as "concerts, lectures, theatrical performances, or choir practices, in which groups of people gather together for extended periods."

That analysis seems dubious if a state allows groups of people to gather in workplaces for even longer periods of time, especially when churches agree to follow the same safeguards (which, among other things, eliminate the "close proximity" that worries Roberts). Employees of warehouses and factories—two types of businesses that Newsom categorically exempted from the restrictions he imposed on houses of worship—are allowed to gather for eight hours at a time, much longer than a church service takes. Even visits to grocery stores, shopping malls, restaurants, or laundromats can easily last as long as a church service. Courts that see no First Amendment problem with special restrictions on religious services seem to be reasoning backward from a predetermined conclusion that state and local governments can do whatever they deem appropriate to protect public health.