Making Amends for Korematsu

The 1944 ruling validated FDR's order to relocate and imprison 120,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants during World War II.

If there is a silver lining to the Supreme Court's summer ruling in Trump v. Hawaii, which upheld President Donald Trump's ban on travel from predominantly Muslim countries, it's that the Court finally denounced its own error in Korematsu v. United States. That 1944 ruling validated Franklin Delano Roosevelt's order to relocate and imprison 120,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants during World War II. It has been a blight on the Supreme Court's record ever since.

Signed by FDR in February 1942, Executive Order 9066 was a brutal and authoritarian document rooted in fear, racial prejudice, and sweeping generalizations unsupported by the data then available to policy makers.

After the Japanese navy's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, fear of a West Coast invasion seized California. The state was home to a large population of Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants, who had made their way east after the Meiji Restoration of 1868 repealed a centuries-old law prohibiting Japanese citizens from emigrating. Many of those newly liberated Japanese settled in California, where they quickly aroused the same paranoid anti-immigration sentiments seen in other parts of the U.S. at the turn of the 20th century.

What did Californians of Western European descent fear? What nativists have always feared: competition. They worried that the Japanese would out-reproduce them; that, if allowed to own land, they would become wealthy at the expense of whites; and that the traditions they brought with them would corrupt American culture.

In response to these concerns, California passed the Alien Land Law of 1913, which prohibited non-citizens from owning property or even signing long-term leases. This restricted Japanese immigrants—many of whom could not obtain citizenship under the terms of the 1790 Naturalization Act—to lower-level farming jobs and short-term housing arrangements. Amendments to the law in 1920 and 1923 codified further deprivations, and then, after Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, Californians were able to close their state almost entirely to Asia.

When the smoke cleared in Hawaii, it was easy for white Americans on the Pacific coast to see their Asian neighbors as potential subversives—not because Japanese Americans openly worshipped Emperor Hirohito, but because they'd already been dehumanized by decades of anti-immigrant politicking. While no loyal American cheered the attack on Pearl Harbor, some citizens used the threat of sabotage as a vehicle to advance their pre-existing prejudices against the Japanese.

Lieutenant General John L. Dewitt was responsible for securing the West Coast during World War II. Relying "heavily on civilian politicians rather than informed military judgments," according to a later investigation, he incorporated citizens' longstanding resentments into a February 1942 report to FDR in which he recommended "excluding" Japanese immigrants and their family members from the West Coast of the United States.

"In the war in which we are now engaged, racial affinities are not severed by migration," Dewitt wrote. "The Japanese race is an enemy race." He saw no reason to believe that Japanese Americans, "barred from assimilation by convention…will not turn against this nation when the final test of loyalty comes." That none had yet betrayed the U.S. was, in his opinion, "a disturbing and confirming indication that action will be taken."

In hindsight, we know that Dewitt was wrong about the military threat posed by people of Japanese descent. The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, formed by Congress in 1980, found no substantiated accounts of sabotage or subterfuge by Japanese Americans living in California during the war. But the public mood at the time would brook no sober analysis on such things—so when Dewitt suggested that FDR begin rounding up Japanese Americans and moving them east to prevent communications with the enemy abroad, the president was all too happy to oblige.

Any person born in Japan or of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast in 1942 was asked to report to their nearest relocation center. Communities that had existed for decades were broken up and their residents transferred to camps in Eastern California, Utah, Arkansas, Wyoming, Arizona, Colorado, Arkansas, and *Idaho. "From Puyallup to Pomona, internees found that a cowshed at a fairgrounds or a horse stall at a racetrack was home for several months before they were transported to a permanent wartime residence," says an article on relocation published by the National Archives.

Many of them never made it back home when the camps began to discharge people in 1944. According to the National Archives, only 30 percent of the Japanese who had been forcefully relocated from Tacoma, Washington, for example, ever returned.

The conditions in U.S. internment camps looked nothing like those in Nazi Germany. Adults worked, children went to school, and there were no gas chambers or heinous, involuntarily medical experiments. But the Japanese—70,000 of them U.S. citizens—were still imprisoned based on racial animus, mindless fear, and lies, and they were still deprived of the liberty, wealth, and relationships they'd built before Pearl Harbor.

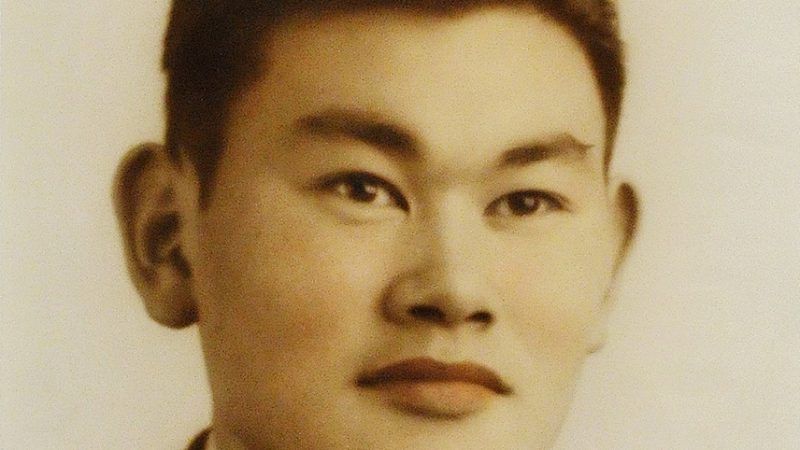

Fred Korematsu was one of them. Born in Oakland, California, to Japanese immigrant parents, Korematsu had supported the U.S. war effort after Pearl Harbor until his Japanese lineage got him fired from a factory job. Ordered to report for internment in May 1942, he refused.

After three weeks on the lam, Korematsu was arrested and tried for violating a federal law that made it a crime to disobey Roosevelt's executive order. He eventually appealed his case to the Supreme Court, where a 6–3 majority led by Justice Hugo Black—a New Dealer and FDR appointee—ruled that mass detention of Japanese immigrants and their American families was not unconstitutional.

Korematsu died in 2005, which means he did not get to see the ruling that bears his name excoriated this year by the same Court that seven decades earlier had defended his imprisonment. He did, however, bear witness to President Ronald Reagan's signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which celebrated its 30th birthday in August.

That law was the product of nearly a decade's worth of research and investigation by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. It called for giving each living survivor of internment—starting with the oldest ones the government could then identify—a tax-free check for $20,000 and a letter from the president apologizing for the government's actions.

"The checks will be consequential," Cressey Nakagawa of the Japanese American Citizens League told the L.A. Times in 1990, when the first letters were sent out. "But most meaningful will be the apology."

The majority opinion in Trump v. Hawaii, authored by Chief Justice John Roberts, does not apologize to Korematsu or even formally overturn the decision, but it comes close. "Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—'has no place in law under the Constitution,'" Roberts wrote.

"This formal repudiation of a shameful precedent is laudable and long overdue," Justice Sonya Sotomayor responded in her dissent. "But it does not make the majority's decision [in the travel ban case] acceptable or right."

*An earlier version of this article failed to mention Idaho, which contained the Minidoka and Kooskia internment camps.