Museum of Drug Policy Pops Up in New York For U.N. Special Session on "World Drug Problem"

Unlike the feckless diplomats a few blocks away, artists presented a clear and devastating picture of the global war on drugs.

For three days this week, the Museum of Drug Policy Pop Up Cultural Hub was open

on Park Avenue in New York City, a few blocks west of the United Nations, which held a special session of the U.N. General Assembly (UNGASS) on the "world drug problem."

As Jacob Sullum wrote earlier today, the confab of global diplomats was typical U.N.: big on platitudes and talk of "action" but short on anything resembling a coherent consensus:

The U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) says the UNGASS participants "delivered a clear message: that they care about the world drug problem, and specifically about the people most affected by this problem." The Saudis are nodding along: We kill because we care.

Unlike the UNGASS, the pop-up museum didn't put forth the pretense that it would be able to end the devastation wrought by the criminalization of drugs around the globe, it merely presented some beautiful, tragic, and evocative expressions of art to put a universal human face on the many casualties of the war on drugs.

A project of the George Soros-founded Open Society Foundations, the museum

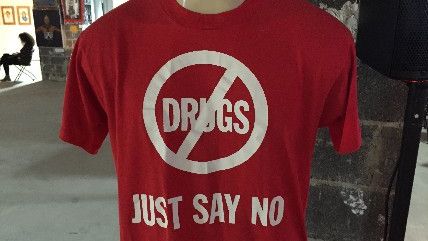

featured a number of very effective exhibits, like a 1980s-era children's board game called "Just Say No!," which featured cards bearing questions like, "What does a drug addict look like?" Artist Zephrey Throwell contributed two renderings of his father "whose life was ravaged by addiction" using crystal meth and his father's ashes as his artistic materials (see right).

Walk-in exhibits included a single occupancy prison cell, a Colombian coca farmer's hut, and a multimedia "Demilitarized Zone," where you could walk through a recreation of a supervised injection facility while films explaining the program played on video screens.

Along the back wall, small pieces of construction paper bearing the names of those lost to addiction or drug-related violence combined to form an image of a 12-foot-high tree, and near the entrance, a bed with a map of the world hung on the wall next to a sign reading, "Globally, 5.5 billion people have limited or no access to adequate pain relief. This is 75% of the world's population."

In the main entrance gallery, the Fuentes Rojas Group hung hundreds of pieces of white cloth embroidered in red — representing handkerchiefs used to dry tears of grief — "to give visibility to the otherwise forgotten victims of violence," particularly the tens of thousands lost as "a direct result of the War Against Drugs launched in 2006 by Mexico President Felipe Calderon." Other handkerchiefs were embroidered in green to represent the "disappeared," the victims of Mexico's drug war whose fate is not yet determined.

Jane Brundidge, a Chicago native who has lived in Mexico City for the past eight years, told me she joined the group because she could no longer bear "living in the American bubble." Instead, she resolved to volunteer her time to help the group's message reach the U.S. via a blog she and her husband operate, which translates Mexican news reports of drug-related violence into English.