Why Bobby Jindal is Wrong to Tell Hyphenated Americans to Lose the Hyphen

They are good for America just the way they are

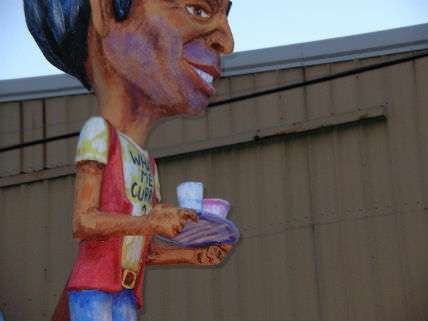

Many social conservatives have been raising the alarm about so-called transnational immigrants or hyphenated Americans not fully assimilating in America. Even Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal, son of Indian parents, chimed in

last week, telling a gathering of Indian-Americans to shed the Indian from their label.

"My dad and mom told my brother and me that we came to America to be Americans. Not Indian-Americans, simply Americans. If we wanted to be Indians, we would have stayed in India," Jindal declared.

As an Indian-American like his parents, I can almost guarantee that his parents said no such thing. They likely came to America for the economic opportunities and then went through a painful sifting process to determine which part of their heritage to keep and which to jettison – and likewise what aspects of their new country to embrace and what to resist. They didn't come consiciously thinking that the minute they stepped foot on American soil, they'd shed all their old ways in toto and grow a new American skin and tell their children to do the same.

Be that as it may, I note in my column at The Week, the assimilability of immigrants isn't a new worry. What's new is the twist that transnational immigrants like me can't love America. The rap against us is that:

In this age of instant communication, we maintain ties with our motherland that prevent us from fully "emotionally assimilating." The fact that we can fly back home in a jiffy when our aunt dies or niece gets married (as I just did last month) means that our assimilation is superficial. Therefore, allowing more of us in, especially when the American educational system's commitment to (forced) integration has been replaced by forced multiculturalism, would undercut the shared civic beliefs that hold America together.

But that's a crude over simplification of the complex psycho-sociology of immigrants:

For starters, the chief barriers to assimilation often stem not from immigrants themselves, but the native born. Just like a new kid trying to break into long-established cliques in school, immigrants find it exceedingly difficult to become fully accepted in American society for the simple reason that the native born prefer to hang out with those more familiar to them. Americans are the most open-minded people on the planet — but connections born out of curiosity are never as deep as those that stem from a shared history and cultural background. It is therefore difficult for immigrants to fully replace old friendships and relationships in their new country. And if they couldn't salve their "psychological amputation" — by instant messaging cousins, or viewing family albums across oceans on Facebook — they wouldn't become more "emotionally assimilated," they'd just be lonelier and more atomized. In other words, their personal downside wouldn't translate into any social upside for America.

But what about [Victor Davis] Hanson's contention that frequent contact means that the homeland never gets relegated to the "romance of memory"? That's actually a good thing…

Go here to read the whole thing.