The FBI Says 'Active Shooter Incidents' Are On the Rise. What Does That Mean?

Decoding a new crime study

The FBI released a report today suggesting that "active shooter incidents" grew more common from 2000 to 2013. Reason readers may wonder how to square that conclusion with the statistics we've published suggesting that mass shootings are not on the rise. There are two answers to that. One involves some potential problems with the FBI's numbers; we'll get to those issues in a moment. The other answer is simpler: "Active shooter" and "mass shooting" do not mean the same thing.

You're forgiven if you didn't get that impression from the press coverage of the FBI report. The Wall Street Journal, for example, called its story on the study "Mass Shootings on the Rise, FBI Says." The New York Times said "F.B.I. Confirms a Sharp Rise in Mass Shootings Since 2000." The Huffington Post went with "FBI Study Finds Mass Shootings On The Rise, Often End Before Police Can Respond." The Daily Beast didn't just use the headline "FBI: Mass Shootings Are on The Rise"; every single sentence in its brief article includes the phrase "mass shooting" or "mass shootings."

While there are competing definitions of mass shooting out there, they all cover crimes that wouldn't fit in the FBI's list of active-shooter incidents; the FBI's count in turn includes events that no one would call a mass shooting. The standard government definition of an active shooter is "an individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a confined and populated area." (It doesn't mention firearms, but the word shooter obviously excludes other means of murder.) The authors of the FBI report tweaked this definition slightly, dropping the word "confined" because they didn't want to leave out crimes committed outdoors. They also excluded killings connected to gang rivalries or the drug trade—a major difference between these numbers and the mass-shooting statistics assembled by criminologists like James Alan Fox, one of the country's leading authorities on mass murder. (For Fox, a mass shooting is basically any homicide with a firearm that leaves at least four people dead.) Another major difference: Rather than basing its definition on how many people were killed, the FBI report focuses on homicidal intent. If the perp only wounds his victims, or if he doesn't even manage to do that, he still gets counted. Fewer than half of the incidents in the FBI report qualify as mass shootings under Fox's definition.

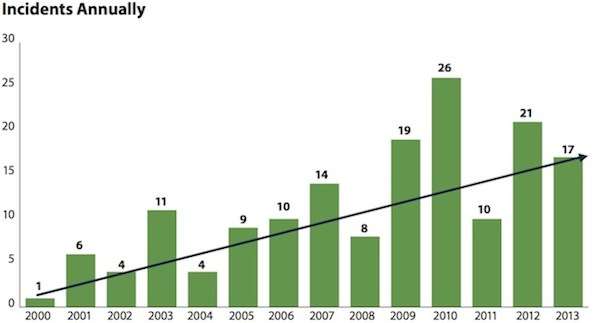

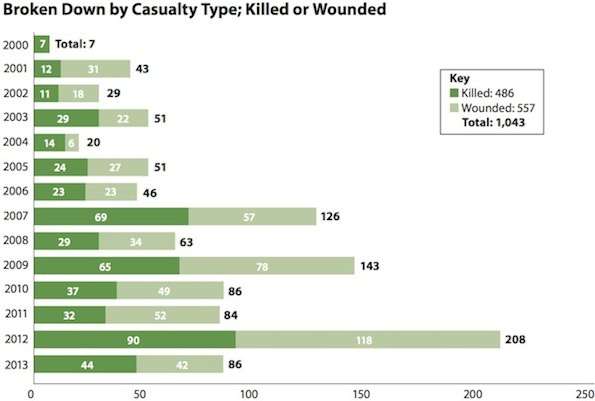

At any rate, the FBI found 160 incidents, which together left 486 victims dead and 557 wounded. (The casualty figures do not include the shooters themselves, though they are often killed or kill themselves in these attacks.) In the first seven years, an average of 6.4 incidents occurred annually; in the last seven years, the figure was 16.4. The bureau also shows the number of casualties increasing over time. Here are the year-to-year data in a couple of charts:

Those are raw numbers, not per capita figures, but by my back-of-the-envelope calculations you still see a rise in the casualty count if you adjust for population growth.

So is it true that these incidents are becoming more common?

Fox isn't convinced. "Unlike mass shooting data," he says, "which come from routinely collected police reports, there is no official data source for active shooter events. Necessarily, these data derived from newspaper searches for the term 'active shooter' and similar words. Not only is the term 'active shooter' of relatively recent vintage (although created after the 1999 Columbine shooting, it wasn't used much in news reports until the past two years), but the availability of digitized and searchable news services has grown tremendously over the time span covered by the data. Thus, it is not clear whether the increase is completely related to the actual case count or to the availability and accessibility of news reports surrounding such events." Fox acknowledges that the new study draws on police records as well as press accounts, but he says the cases still have to be initially identified by searching news reports, "with police department records helpful for the details." (Sure enough, when the FBI paper identifies its sources, it cites several studies that rely on such searches.)

Grant Duwe is skeptical about the numbers too. Duwe is the director of research and evaluation at the Minnesota Department of Corrections; each year he compiles a list of mass shootings that take place in public and are not a byproduct of some other felony. (He would not, for example, include a stick-up man who shoots several people while fleeing the police.) His figures show an unsteady decline from 1999 to 2011 and then a spike in 2012, which is not the pattern you might expect from those active-shooter numbers. While he appreciates some aspects of the FBI's report—he singles out its "detailed breakdown of the specific locations where these incidents occurred"—he has issues with it as well, noting that 10 of the mass shootings on his list are missing from the new study. (These omissions appear throughout the period covered, without being clustered at either the beginning or the end.) "Given that incidents involving fewer victims generally attract less attention," he adds, "I imagine the amount of underreporting for these cases is greater." Since the FBI's list "is neither a random nor an exhaustive sample," he concludes, "it's inappropriate to make any claims—which this report does—about trends in the prevalence of cases meeting their definition." He thinks it possible that such a rise has happened, but he doesn't think the report proves it.

For Fox, a vocal critic of the way the phrase "active shooter" has come to be used, the chief concern is that people understand that "these events are exceptionally rare and not necessarily on the increase." While he fully supports serious efforts to prevent and prepare for such crimes, he also thinks it "critical that we avoid unnecessarily and carelessly scaring the American public with questionable statements about a surge in active shooter events."