Life and Death of a Russian Freedom Fighter

There is a certain symbolism in the fact that Valeria Novodvorskaya died just as the Putin regime was being fully exposed as the gangster state that she had always said it was.

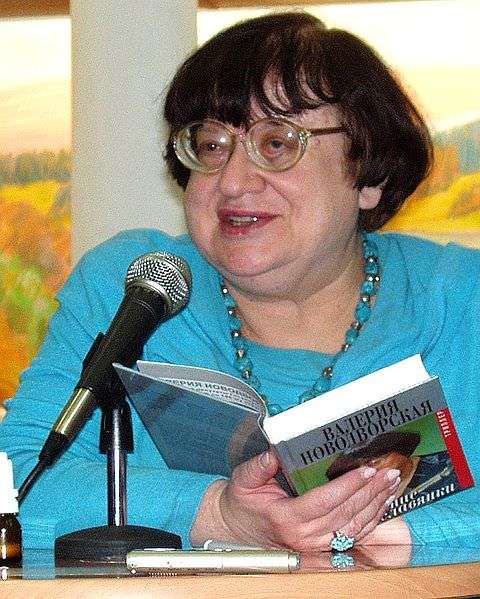

Valeria Novodvorskaya, the firebrand Russian activist and writer who died in Moscow on July 12 at the age of 64, was practically unknown abroad and had a somewhat scandalous notoriety at home. Enemies derided her, often in crudely misogynist terms, as a demented Russia-hating hag; even many allies viewed her as something of an embarrassment, a ridiculous old woman prone to saying things that made the already marginalized liberal opposition look crazy. In death, she was quickly and almost literally canonized by the same opposition. Many said that they were only now beginning to understand what a great soul had lived in their midst, and was now gone. "The things we whispered, she said loudly," wrote former tycoon and political prisoner Mikhail Khodorkovsky. "The things we were willing to tolerate, she was not."

On the other side, some gloated about "Granny Lera" burning in hell—but others voiced respect for her courage and conviction. In a surprising gesture, Vladimir Putin, whom she had compared to Hitler long before it was fashionable, expressed condolences; prime minister and former (puppet) president Dmitry Medvedev praised not only her talent and bravery but, presumably with a straight face, her contributions to democracy in Russia. An odd piece in the pro-government Izvestia that teetered between mockery and eulogy said that she was "a walking joke" who, after she died, "forced everyone, as if by inaudible command, to take her seriously."

To say that Novodvorskaya, whom I briefly met on a trip to Moscow in 1991, was an extraordinary woman would be an understatement. She was a fighter as tireless as she was fearless, as unbowed by state reprisals as by her own failing health; she was also a powerful writer of keen intelligence and vast knowledge who wrote on history and literature as well as politics. She was a towering figure of her age; and, like many such figures, perhaps especially in Russia, she was a creature of extremes and contradictions. Her passion for freedom and justice, and her intense hatred of communism, sometimes led her to strange places. Yet fellow dissident Alexander Skobov, a democratic socialist whose views were very different from Novodvorskaya's free-market radicalism, summed it up best when he wrote that the only people with a right to judge her were those who equaled her courage in confronting tyranny.

Courage was one thing Novodvorskaya never lacked. In her 1993 memoir, On the Other Side of Despair, she recalled that at 15, she marched into the local draft board office demanding to be sent to Vietnam. She admired Joan of Arc and Spartacus, going to see the Stanley Kubrick film more than a dozen times. (Spartacus was widely shown in the Soviet Union as a glorification of the revolutionary struggle; little did the authorities suspect that it was helping nourish a rebel who would take up that struggle against them.) At 17, she read Solzhenitsyn's fictionalized account of Stalin's gulag, A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, and quickly concluded that the Soviet regime was as great an evil as the slavery against which Spartacus rebelled. "Instead of shedding tears," she wrote, "I regarded it as a gift from fate": she would get to be a fighter after all.

Still in high school, she spoke sedition in the classroom and wrote heretical essays, miraculously escaping trouble with the help of a few friendly teachers; after starting college, she wasted no time organizing an underground student group. The shock of the 1968 Prague Spring and its suppression by Soviet tanks further radicalized Novodvorskaya. In December 1969, at the age of 19, she threw a pack of typewritten leaflets—some with a proclamation, others with an angry poem of sarcastic thanks to the Communist Party—from the balcony of a major Moscow theater. A sympathetic usher urged her to run, but she would do no such thing; her well-thought-out plan was to get arrested, scare the KGB with tales of a large secret network of subversives, make fiery speeches at a public trial, and then get executed, shattering societal apathy with her martyrdom and willing her imagined revolutionaries into existence. "This plan took no account whatsoever of practical reality; other than that, it was perfect," Novodvorskaya noted wryly in her memoir.

Instead, the would-be Joan of Arc was quietly hustled off to prison and eventually, after refusing to repent, hospitalized for "sluggish schizophrenia"—the standard made-up diagnosis for dissidents. It was a far worse punishment than prison or labor camp; inmates were given psychotropic drugs with nasty side effects and excruciatingly painful injections. When Novodvorskaya was released in 1972, her health was broken—at 22, she had a full head of gray hair—but her spirit was not: she went right back to clandestine activities as a dissident, distributing illegal samizdat literature, trying to organize a political party, participating in a short-lived attempt to create an independent labor union. There were more arrests, more prison time, another stint in a psychiatric hospital.

In the late 1980s, came Mikhail Gorbachev's glasnost and perestroika, and Novodvorskaya threw herself into activism with a new abandon, and with a radical message that went beyond reform to call for the dismantling of the Soviet system and a rejection of state socialism. She got arrested again, a total of 17 times between 1987 and 1991—the last time for publishing an article titled "Heil, Gorbachev!" in the newsletter of her new party, the Democratic Union. The hated regime fell; but Novodvorskaya's joy was short-lived. Boris Yeltsin's rule—during which she made her single, failed attempt to run for office—brought increasingly bitter disappointment, particularly at the war in Chechnya. Then, ex-KGB officer Putin rose to power, bringing back the Soviet anthem, crushing Chechnya, and mounting an increasingly undisguised assault on Russia's fledgling freedoms.

Novodvorskaya's worst disappointment was in the Russian people. As a young Soviet dissident, "I believed in the people," she said in a radio interview. "I sincerely believed that the people were oppressed by the Communist Party, that they were forced and threatened into submission. That, as soon as they were no longer being raped, they would immediately, joyfully, enthusiastically start taking advantage of their freedoms and rights and set about building capitalism." For a while, this faith seemed validated by the massive anti-Soviet protests of the late 1980s and the crowds that came out to defend the Russian White House against the hardline communists' coup in August 1991. By the mid-1990s, that illusion was over. In the Putin years, Novodvorskaya freely admitted that if the Russian masses rose up, it would not be to bring about the Western-style liberal democracy she idolized but some hideous hybrid of "red-and-brown," communism and fascism.

In her disillusionment, she transferred her hopes to neighboring ex-Soviet countries where she saw the spirit of freedom thriving, and where Putin's Russia was seeking to squash it: specifically, Georgia and Ukraine. In her final months, her columns for the independent website Grani.ru were filled with passion for the Maidan revolution, as well as frustration and bitterness at the West's lack of resolve to back Ukraine's struggle against Russian aggression. (While Novodvorskaya was close to libertarian views on economic and social issues—on several occasions, she expressed admiration for Ayn Rand—she was also, in American terms, an unabashed neocon, a staunch believer in American power and leadership as the world's best hope for liberty; her political icons were Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, as well as Czech dissident-turned-president Vaclav Havel.)

She said eyebrow-raising, and sometimes hair-raising, things. For instance, that she would welcome an American attack on Russia: "It would be better for Russia to become a state within the United States. But I think that the Americans don't need us." Or that the Russian character was so corrupted by centuries of slavery that a mere 5-10 percent of the population had the capacity for freedom and dignity—and they were the only ones who truly mattered, while the rest were "reptiles," "amoebas" or "dinosaurs." At the end of On the Other Side of Despair, she wrote that someday Russia might be reduced to "a charred wasteland, a vast forest, or a mass grave"—but at least "there will never be a new Gulag Archipelago here."

Comments like these led many to say that Novodvorskaya was not only a fanatical Russophobe but "a Bolshevik in reverse," willing to sacrifice millions for her liberal capitalist utopia. But to a large extent, such words were the product of pain and anger—and, in part, deliberate provocation. There were other times when she wrote of Russia with a tender, unrequited strange love. A darkly funny 2009 column titled "I'm Married to Putin," in which Novodvorskaya caustically described her relationship with the Kremlin autocrat as "classic Russian family life"—spouses who can't stand each other but still share a home—ended with a poignant prophecy: "I know he'll outlive me. He's young and athletic, I'm old and sick. And then I feel scared: our sad little child, which got dropped on its head at the maternity hospital and has cerebral palsy and mental disabilities—a child called Russia—will be left in his hands, with no one to pity the poor orphan."

Sometimes, she found herself at odds with the human rights activists who were her usual allies, as she argued that absolutist notions of political freedom for all were helping empower enemies of freedom such as communists or Islamist fanatics. Yet, when a Ukrainian online magazine asked her in a 2008 interview whether there would be "hangings" if she somehow came to power in Russia, Novodvorskaya reiterated her staunch opposition to the death penalty: she would do nothing more than ban communist and fascist parties and forbid their adherents to hold public office. In a qualified eulogy for Pinochet, she insisted that the Chilean dictator deserved credit for stopping a likely communist takeover; but she also readily admitted that, had she lived in Chile, she would not have survived under his regime because she would have felt compelled to defy it. From someone else, this would have been an empty boast; in Novodvorskaya's case, no one could doubt that she meant it.

She was, inevitably, a maverick who mostly walked alone. In the Putin years, she sometimes got invited to appear on talk shows on government-run TV channels from which more even-tempered liberals, such as chess champion Gary Kasparov or former governor Boris Nemtsov, had long been blacklisted; some suspected it was a deliberate strategy to discredit the opposition, not only because of Novodvorskaya's reputation for extremism but because she was seen as an oddball.

In a society where traditional sexism is still strong and overt, her gender and her appearance made her all the more vulnerable to ridicule; a heavy woman in thick glasses, with short-cropped hair, a deep voice and an often brusque manner, she was often mocked as mannish or sexless. She met the mockery head on, defiantly sporting conspicuously feminine, almost girly clothing and jewelry—and freely admitting that she was a virgin (her life's mission, she explained, had left no place for family or romance, and sex for its own sake seemed a waste of time). She took sexism in stride—though in 2011, after years of dismissing feminism as silly, she wrote a sympathetic column about women's battle for equality. And, surprisingly often, she managed to win respect: the Russian edition of the men's magazine, FHM, which had a policy of doing extended interviews only with men who could be role models for its readership, made an exception for Novodvorskaya as "the only real man left in Russian politics."

She was often criticized for having a black-and-white outlook—and she did (though it extended only to institutions and actions, not individuals: she was flexible enough to warm up to erstwhile foes such as Gorbachev). A passionate J.R.R. Tolkien fan, she sometimes explicitly framed the battle against the authoritarian state as a Lord of the Rings-like clash of good and evil. One might say that she never outgrew teenage rebellion; many people who knew her described her as oddly childlike. And yet, under a brutally repressive system, such intransigence and moral absolutism, however naïve, may be essential to having the strength to fight and persevere against all odds. After her death, the writer Dmitry Bykov, who had once lampooned Novodvorskaya as a pyromaniac yearning to burn down the world in a cleansing fire, penned an emotional tribute to her unbreakable honor and concluded, "Surely people of this breed—rare but most necessary—cannot be extinct in Russia. Otherwise, what's the point of it all?"

There is a certain symbolism in the fact that, as Russian-Ukrainian commentator Vitaly Portnikov has pointed out, Novodvorskaya died just as the Putin regime was being fully exposed as the gangster state that she had always said it was. Some mourned her death as the end of an era, the passing of "the last of the dissidents." Others saw her life as an embodiment of undefeated freedom and hoped that her death would inspire other fighters. A widely distributed tweet (wrongly attributed to the popular singer Alla Pugacheva) said, "If a million people in Moscow turn out for Novodvorskaya's funeral and refuse to go home, Putin is done. Come on, Russians!" That did not happen; but enough people young and old turned out to say good-bye to this unique woman, standing for hours in the scorching sun, to keep the faith in her spirit. As the coffin with her body left the Sakharov Center, where the funeral was held, the crowd took up a chant: "Heroes do not die."

A version of this column originally appeared at RealClearPolitics.