Jeff Mizanskey Is Serving Life in Prison for Marijuana

Rapists and murderers come and go, but he's there for the duration.

As I prepared to leave home for my interview with Jeff Mizanskey I looked up the address of the prison where he is held. In disbelief, I typed the characters into the GPS on my phone.

8200 No More Victims Road.

Jeff Mizanskey is serving a life sentence without parole for marijuana. He has been in prison since right after I was born 21 years ago. Jeff is the only person in Missouri sentenced to die behind bars for marijuana, a victim of the state's rather unique three strikes law.

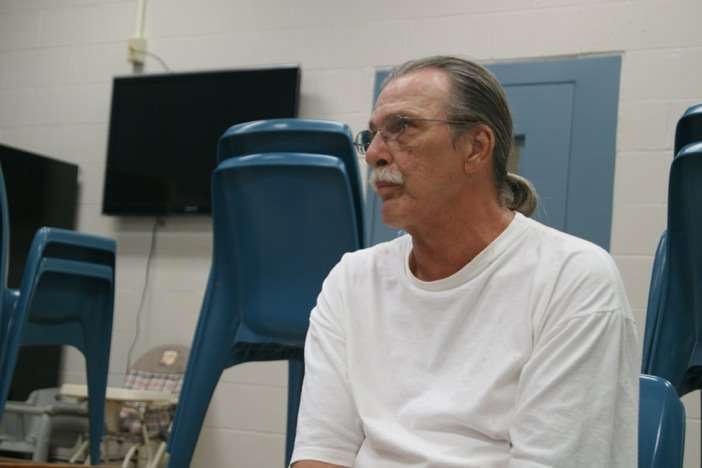

A prison guard escorted Jeff into the visiting room where I had set up for our interview. As he walked in and introduced himself, I was struck by just how much he reminded me of my grandfather (he has grandchildren of his own). Jeff is soft-spoken, calm, and articulate, and holds an interesting perspective on his sentence. His perspective is balanced between accepting his fate as a punishment he earned and at the same time being unable to shake the nagging feeling of unfairness that comes with spending life behind bars while murderers are released.

Jeff has watched dozens of convicted rapists and murders, housed in his cellblock, walk out the doors as free men over the past 21 years. Many have re-offended and were sent right back to prison. Meanwhile, Jeff has completed over a dozen rehabilitation programs while incarcerated, and now mentors other inmates to convince them to learn from his past. He doesn't hesitate to acknowledge the mistakes he has made, but feels strongly that his punishment was disproportionate to his crime.

Missouri's three strikes law landed Jeff his life without parole sentence. Around half of states have some type of three strikes law on the books. In almost all of these states the statutes apply to violent crimes—murder, rape, assault with a deadly weapon, etc. In Missouri, Jeff racked up all three strikes without ever committing an act of violence. He was a working class guy with a small side gig as a low-level pot dealer. He never hurt anyone, never brandished a weapon, and never sold to children.

Jeff calmly told me his story from across the table in the visiting room. The guard stared at the floor as he half-listened from thirty feet across the room.

Strike one came in 1984 when Jeff sold an ounce of marijuana to a close relative, who at some point gave or sold it to an undercover police officer. The relative told police where he got it in exchange for leniency, and his testimony was enough to get a search warrant of Jeff's home. The half-pound of pot found during the search landed him with his first felony conviction and five years probation.

Strike two came in 1991. Police again received information from an informant that was sufficient to obtain a search warrant of Jeff's home. This time, they found less than three ounces of cannabis, but it was still more than the one and a quarter ounces needed to trigger a felony charge. Unable to afford the legal fees necessary to fight the charge in court, he pleaded guilty for the second time.

Just two years later, Jeff gave a friend a ride to a motel. The friend was there to buy a few pounds of pot from a supplier, who was once again working with the police and had helped them set up a sting operation. Jeff accompanied his friend into the motel room and allegedly handled a package of marijuana during the transaction. He was arrested with what would end up being his third strike as they left the parking lot. Jeff has been in a cell at the maximum security Jefferson City Correctional Center (JCCC) ever since, nearly 21 years and counting.

The JCCC is an impressive complex. As I drove up to the facility on a sunny summer morning last month, the first thing I noticed was the facility is enormous. The sheer size of the massive campus, which sprawls hundreds of acres and imprisons thousands of human beings, was stunning. I'd seen smaller universities. Hell—on my way down, I'd driven through smaller towns with fewer people.

Jeff is housed with rapists and murderers because of his life sentence, but the prison guards don't treat him like one. When I first entered the facility, I was assigned a prison guard escort. After he lightly searched my interview equipment for contraband, we began navigating the dozen or so remotely controlled doors between the prison entrance and the visiting room we'd be using. On the way there, the guard made small talk and asked whom I was interviewing. When I told him about Jeff he didn't mince words about the failures of our judicial system. I could certainly understand how keeping Jeff in a cage would just feel silly to a guy who deals with violent criminals every day.

During the interview, the guard stayed on the other side of the room from the table where the interview was taking place. There were no restraints on Jeff—he was free to walk into the visiting room freely and shake my hand. Near the end of the interview, the guard briefly left us alone in the visiting room. It was clear that despite being assigned to live with rapists and murderers, Jeff did not fit in with violent offenders.

I asked Jeff about his future. He told me calmly that all of his appeal options have been exhausted. Unless the Governor of Missouri grants Jeff clemency and sets him free, he will likely die there. He will never know his grandchildren, or his great-grandchild on the way, outside the walls of the sprawling Jefferson City Correctional Center.

As I drove away from the prison, down the very visibly marked No More Victims Road, I thought about the man, and the horribly cruel irony, that I was leaving behind. Unless the Governor of Missouri intervenes and grants clemency, Jeff will die behind bars at 8200 No More Victims Road, having never victimized anyone in his life.

Outraged by Jeff's life without parole sentence for cannabis? You can contact Missouri Governor Jay Nixon to ask him to grant clemency here.

X