New on NRO: "This Constitution Day, Celebrate the Triumph of Originalism"

"As we celebrate the Constitution’s 238th birthday, originalism is now the dominant approach — on the left and the right — to interpret the Constitution."

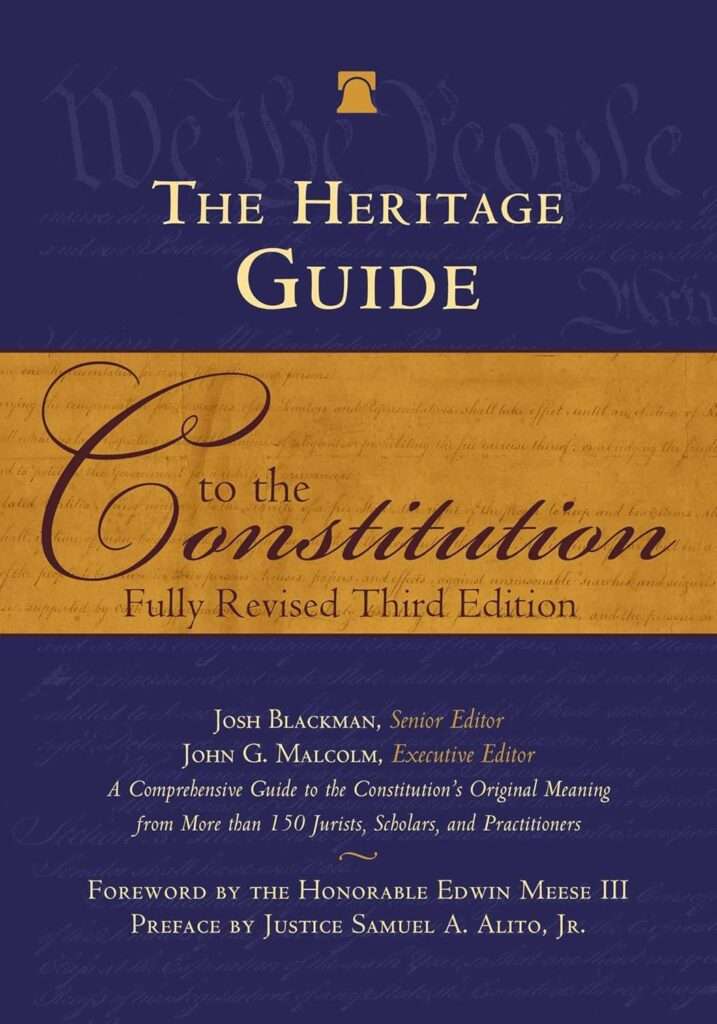

In honor of Constitution Day, and the launch of the Heritage Guide to the Constitution, John Malcolm and I authored an essay on National Review Online, titled: "This Constitution Day, Celebrate the Triumph of Originalism."

In honor of Constitution Day, and the launch of the Heritage Guide to the Constitution, John Malcolm and I authored an essay on National Review Online, titled: "This Constitution Day, Celebrate the Triumph of Originalism."

Five decades ago, originalism wasn't even an -ism. In the academy, at the bar, and on the courts, the Constitution was interpreted as a living, breathing document. Contemporary values mattered more than text, history, and tradition. Yet today, as we celebrate the Constitution's 238th birthday, originalism is now the dominant approach — on the left and the right — to interpret the Constitution.

Even Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said during her confirmation hearing, "I believe that the Constitution is fixed in its meaning" and that looking to "original public meaning" is "a limitation on my authority to import my own policy." Still, critics charge that lawyers and judges, lacking Ph.D.s, are not qualified to perform historical research and that originalism is partisan and lacking in any sort of neutrality. These claims do not hold up.

For nearly five years, a coalition of 30 judges, 60 academics, and 60 practitioners united to assemble a definitive, comprehensive, and neutral statement about the entire Constitution's original meaning. This ground-breaking research will be published in the fully revised third edition of the Heritage Guide to the Constitution. Justice Samuel A. Alito wrote in his preface that "the new edition of The Heritage Guide is a great place to start" for all Americans who "want to understand what our Constitution means."

These judges, scholars, and advocates who contributed to this book teach us how to determine the Constitution's original meaning in the right chronological order: the history before 1787; the records of the Constitutional Convention; the ratification debates; early practice in the legislative and executive branches; and finally, judicial precedent. More than 200 essays break down every clause of the Constitution through these five steps.

Here are the five steps:

First, what were the origins of the text in the Constitution? . . . .

The second part of the originalist inquiry focuses on what the 55 delegates accomplished in Philadelphia to frame the Constitution. . . .

The third, and perhaps most important phase, was the ratification debates. . . .

The Constitution was formally ratified in 1788, and the new government assembled in 1789. At that point, the fourth phase began. How did the early actors in our government understand the Constitution? . . .

The fifth inquiry, finally, turns to the courts: What have judges, especially on the Supreme Court, said about a particular clause of the Constitution?

We conclude:

This five-step approach reflects originalist best practices that students, lawyers, and the judiciary should follow. The Supreme Court has often referred to the Constitution's text, history, and tradition to understand the document's original meaning. It is important to approach these inquiries in the right order.