Machine Gun History

Law and technological development

While legal scholarship on firearms has grown tremendously since I first started writing on the issue in the late 1980s, one topic that has never been addressed in detail in any law journal is machine guns. My new article in the Wyoming Law Review, Machine Gun History and Bibliography, aims to fill the gap.

The article appears in a symposium issue of the Wyoming Law Review, based on papers presented at a 2024 conference held by the law school's Firearms Research Center, where I am a senior fellow. This was the first law school symposium ever on the National Firearms Act of 1934, one of the two foundational federal gun control statutes.

Of the five other articles in the symposium issue, one of my favorites is The Tradition of Short-Barreled Rifle Use and Regulation in America, by Joseph G.S. Greenlee. While this is not the first article about NFA regulation of short-barreled rifles (SBRs), it is the first to examine in depth the history of SBRs, which before the 1934 NFA imposed a $200 tax on them, were quite common. And they're common today too; as of May 2024, there were 870,286 registered in the National Firearms Registration and Transfer Record, which is maintained by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives. (ATF, Firearms Commerce in the United States, Statistical Update 2024, p. 12.)

My other favorite in the symposium is Stephen Halbrook's The Power to Tax, The Second Amendment, and the Search for Which "Gangster' Weapons" to Tax. In brief, the NFA bill as introduced also included handguns, but they were removed from the bill at the insistence of the National Rifle Association and the National Guard Association, which at the time were very closely allied. The inclusion of SBRs and short-barreled shotguns (SBSs) was simply an effort to prevent evasion of the draft restrictions on handguns. Once handguns were deleted from the NFA bill, there was no longer any reason for the bill to include SBRs or SBSs. No testimony or congressional statement claimed that either of these firearms types were a particular crime problem.

My own article, on machine guns, does not delve into legislative history, nor does it make any arguments pro or con about special laws for machine guns. Rather, the articles aims to be useful to courts, lawyers, and scholars in two ways: First, the article explains the statutes, regulations, and other important legal texts for American machine gun law. Second the article provides a history of the development of machine guns and their impact on warfare, including a comprehensive bibliography of books for each machine gun type. The Article begins with the 1862 Gatling gun and continues through the present.

Here is the abstract:

This Article provides an introductory history of machine guns and books about them. First, the Article describes federal machine gun laws and regulations, and related legal resources. Then the Article presents the historical development of machine guns from 1862 to the present, covering the various types of machine guns: heavy, medium, light, general purpose, submachine gun, machine pistol, and assault rifle.

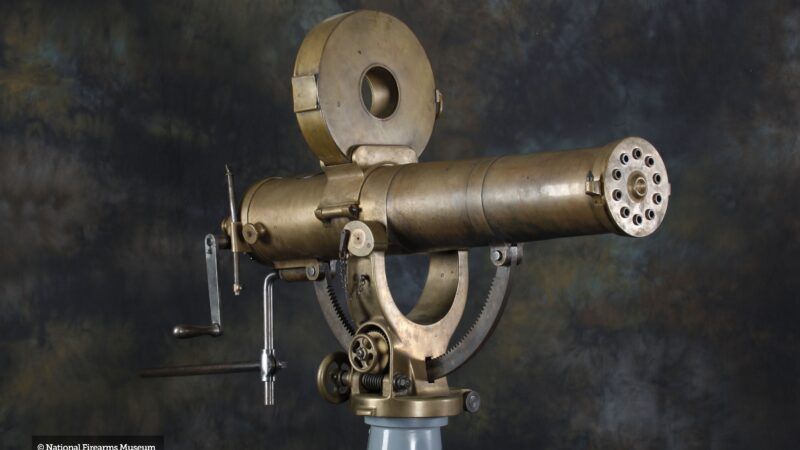

The first machine gun to achieve broad commercial success was the Gatling gun, invented during the American Civil War. Although the Gatling had little effect on that war, shortly thereafter the Gatling gun and other manual machine guns started to change warfare. Later, heavy machine guns such as the automatic Maxim gun, and its successor, the Vickers gun, dominated battlefields. Towards the end of World War I, the heavy machine gun was dethroned from its supremacy by the widespread adoption of new, portable light machine guns, which could be used to suppress an enemy machine gun nest while other troops advanced.

In the subsequent two decades, especially during World War II, machine guns that were easily portable by a single soldier became much more common, such as the Thompson submachine gun widely used by American and British forces. During the Cold War, the assault rifle, no bigger than an ordinary rifle, became increasingly important. Most influential, almost always for ill, was the Soviet Union's AK-47 and its progeny. The American counterpart, the M16, proved much less effective in battle, at first due to technical problems, and everlastingly because of its puny bullet.

Improvements in metallurgy, manufacturing, and design have improved the quality of infantry machine guns. But a soldier with a machine gun on a battlefield in the third decade of the twenty-first century will likely be using a machine gun of a broad type that was already in widespread use by the 1950s.

Besides the machine guns named in the abstract, some of the other machine guns covered in the article include the Lewis Gun, the execrable French Chauchat, Browning Automatic Rifles, Browning Machine Guns, the Finnish Suomi, the British Bren Gun, Sten Guns, Grease Guns, the many German and Soviet innovations of WWII, plus Cold War and subsequent machine guns from companies such as Belgium's Fabrique Nationale and Germany's Heckler & Koch, the American M14 and others, and lastly the modern machine pistols from Uzi, MAC, and Heckler & Koch. The Article concentrates on infantry arms, with only passing attention to aircraft-mounted machine guns.

Finally, I would like to thank the staff of the Wyoming Law Review for an outstanding job on editing and cite-checking. With over 120 published journal articles, I have been through the cite-check process many times, and the Wyoming process was among the very best. Their rigor much improved the precision of the article, and the editors had a strong knowledge of firearms.