Reacting to the Possibility of Slippage—The Slippery Slope Inefficiency and the Ad Hominem Heuristic

[For the last month, I've been serializing my 2003 Harvard Law Review article, The Mechanisms of the Slippery Slope, and I'm finishing it up this week.]

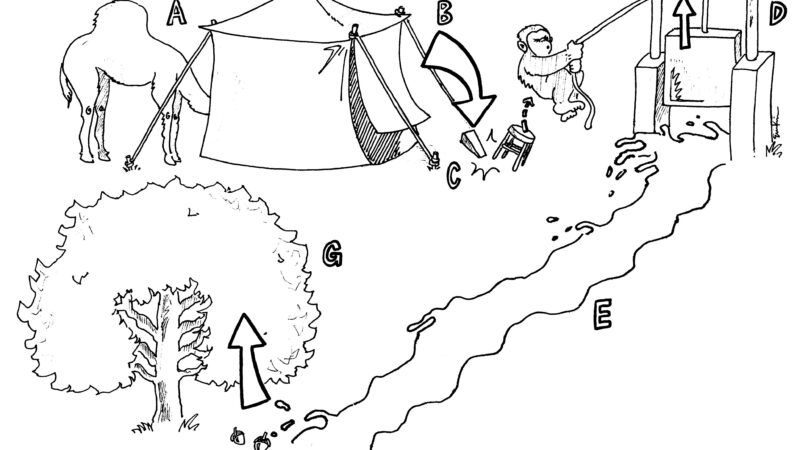

As with other slippery slopes, the danger of a political momentum slippery slope creates a social inefficiency: the socially optimal outcome might be A, but it might be unattainable because some people who support A in principle might oppose it for fear that it will lead, through political momentum, to B.

This slippery slope inefficiency might sometimes be avoided by coupling a proposal supported by one side with a proposal supported by the other, for instance a new gun control with a relaxation of some existing control. This isn't just a compromise that moves from the initial position 0 to a modest gun control (A) but not all the way to a strict gun control (B)—such compromises are still moves in one direction and may lead legislators to upgrade their estimate of the gun-control movement's power. Rather, it's a proposal under which both sides win something and lose something, which should have no predictable effect on legislators' estimates of either side's strength.

Another reasonable reaction by B's opponents, though, may be to adopt the ad hominem heuristic, the presumption that one should usually oppose even modest proposals A that are being advocated by those who hope to implement more radical proposals B later. Acting this way might seem too partisan or even ill-mannered; a culture that values friendly disagreement may frown on people saying "It's not A that worries me so much as the people who support it, and I want them to lose on A because I want them to be seen as losers." Moreover, if overt concern about political momentum slippery slopes is seen as distasteful, the desire to hide this concern will tempt people to be disingenuous.

Still, it seems to me that voters or legislators who strongly oppose B may rightly choose to oppose anything that could help bring B about, even to the point of trying to block passage of an intermediate matter A in order to diminish the movement's political momentum.

[* * *]

Stepping back though, we might want to ask: How can we avoid the slippery slope inefficiency—again, the situation where a potentially valuable option A, which would pass if considered solely on its own merits, is defeated because of swing voters' reasonable fears that A will lead to B? Various tools can help prevent this slippery slope inefficiency by decreasing the chance that A could help bring about B, and thus increasing the chance that A will be enacted. My article discussed three such tools: (1) strong constitutional protection of substantive rights; (2) weak rational basis review under equal protection rules; and (3) proposals in which both sides win something and lose something, thus preventing either side from gaining political momentum. We may want to look for other such tools.

For instance, to what extent can interest groups use their permanent presence, and their continuing relationships with legislators and members of opposing advocacy groups, to work out deals that can prevent slippery slope inefficiencies—deals that unorganized voters could not themselves make? Can such deals be reliable commitments, even though they aren't constitutionally entrenched, or is there too much danger that future legislatures will overturn the deals?