Enforcement Need Slippery Slopes

[This month, I'm serializing my 2003 Harvard Law Review article, The Mechanisms of the Slippery Slope.]

There are many possible multi-peaked preferences slippery slopes besides the cost-lowering slippery slope; one example is the enforcement need slippery slope.

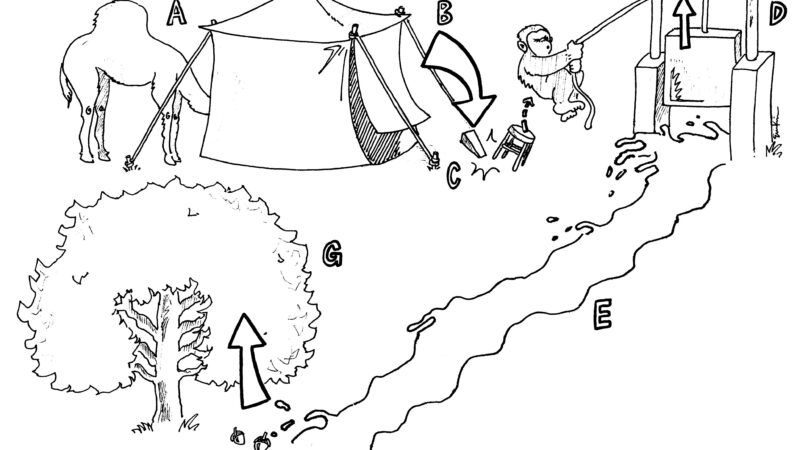

Imagine marijuana is legal, and the question is whether to ban it. Some prefer to keep it legal (0), others want to ban it but enforce the law lightly (A), and others want to ban it and enforce the law harshly, with intrusive searches and strict penalties (B).

But say also that some people would prefer 0 best of all (they'd rather keep marijuana legal), but once marijuana is outlawed they would think that position B (strict enforcement) is better than A (lenient enforcement). "Laws should be enforced," they might argue, "because not enforcing them only teaches people that law is meaningless and that they can violate all sorts of laws with impunity." {See, e.g., Henry F. Pringle, The Life and Times of William Howard Taft (1964) (describing Taft as being opposed to Prohibition before it was enacted, "on the ground that temperance by national law would be difficult or impossible to enforce," but then being willing, as "a passionate zealot for enforcement of laws," to uphold a variety of harsh enforcement mechanisms, such as warrantless wiretaps and prosecutions both by state and federal authorities for the same crime).} Obviously, if they thought the law was extremely bad, they would have preferred that it be flouted with impunity rather than strictly enforced. But let's assume they think the law is only slightly unwise, whereas leaving such a law unenforced is very unwise. We again see a multi-peaked preference—people like A least, preferring either extreme over the middle.

Let's assume, as before, that it takes at least a 55% supermajority to shift from the status quo, and let's assume—again, as a stylized hypothetical, though I hope a plausible one—that the group breakdown is as follows:

| Group | Most prefers | Next preference | Most dislikes | 0→A | A→B | 0→B | Attitude | Voting strength |

| 1 | 0 | A | B | "Restrict marijuana as little as possible" | 10% | |||

| 2 | 0 | B | A | + | "Restricting marijuana is bad, but contempt for the law is even worse" | 20% | ||

| 3 | A | 0 | B | + | "A little restriction is good, but hard-core enforcement is very bad" | 20% | ||

| 4 | A | B | 0 | + | + | "A little restriction is good, and having no restriction is very bad" | 10% | |

| 5 | B | 0 | A | + | + | "Marijuana is bad, but contempt for the law is even worse" | 10% | |

| 6 | B | A | 0 | + | + | + | "Marijuana is bad; do as much as you can to stop it" | 30% |

Given these preferences, a proposal to shift from position 0 (legal marijuana) to B (a sternly enforced marijuana ban) would fail: it would get the votes of groups 4, 5, and 6—only 50%. But a proposed 0→A shift (to a weakly enforced ban) would succeed, with a 60% supermajority coming from groups 3, 4, and 6. Once A is enacted, a proposed A→B shift would also succeed, with the votes of groups 2, 5, and 6, also 60%. And then shifting from B back to 0 would be impossible, since such a proposal would only get the votes of groups 1, 2, and 3, just 50%.

In this hypothetical, decision A wouldn't change anyone's underlying attitudes; rather, it would lead one small but important swing group (the 20% of the voters in group 2) to vote for B, based on their preexisting preference for B over A, even though that group would have opposed B had the status quo remained at 0. {Decision A would lead the 10% in group 4 to oppose B, but that would be offset by group 2's 20%.} Even when only a minority of voters (30%, groups 2 and 5) exhibits multi-peaked preferences, and an even smaller minority takes the enforcement need view that "we don't much like the law but we dislike people flouting the law even more" (20%, group 2), moving to A can cause slippage to B.

{The percentage of group 2 voters—the ones whose multi-peaked preferences ultimately cause the slippery slope—could theoretically be even lower than 20%. For instance, if the groups' voting strength is divided not 10/20/20/10/10/30 but 42/2/2/0/0/54, slippage would still take place (assuming that a policy change requires a 55% supermajority). I chose to use the 10/20/20/10/10/30 breakdown because it seems more plausible than the 42/2/2/0/0/54 breakdown, but of course these are all just stylized models. The important point is that under plausible conditions, the multi-peaked preferences slippery slope can happen even when a minority of all voters have multi-peaked preferences.}

The lesson, then, is for the moderates in group 3, who like A but worry that their support for A would eventually help bring about B, which they dislike most of all. They should ask themselves: "What fraction of our current anti-B coalition will start backing B if we enact A?" If the answer looks high enough—as it is in this hypothetical, and as it may be in many (though far from all) real-world scenarios—group 3 members may want to resist the original move to A, even if they like A on its own.

This analysis suggests that when people consider a proposal A, they should also think systematically about:

- what enforcement problems might arise after A is enacted;

- what new proposal B might become more popular as a means of fighting these enforcement problems;

- whether this new B would be harmful enough and likely enough that the danger of B being enacted justifies opposing A; and

- whether there's some way of minimizing the risks that B will come about, perhaps by coupling A with some up-front assurances that B will be rejected.

Unfortunately, though these points aren't rocket science, we often don't think about them in an organized way.

[* * *]

By the way, I think this tendency to want to enforce the law once it's enacted—even if one wasn't that enthusiastic about the law when it was proposed—is pretty common; here are some factors that may reinforce it:

[1.] A's enactment may lead people to change their views (see the discussion of attitude-altering slippery slopes in coming posts), and to choose B as their preferred option rather than the second-best.

[2.] People often tend to dislike those who are violating the law and getting away with it, which may lead them to focus more on suppressing lawbreaking than on the merits of the underlying law.

[3.] Banning conduct may sometimes change the makeup of the group that engages in the conduct. A marijuana ban, for instance, would drive out the most law-abiding dealers and instead attract criminal ones; it may also lead some otherwise law-abiding users to quit and still others to hide their use. The person whom voters see as the typical marijuana user or dealer will thus be much less sympathetic than before—and more voters may therefore support the law coming down hard on him.

[4.] People who think most laws are generally good may develop what we might call an "enforcement heuristic," the rule of thumb that more enforcement is usually better than less. These people may thus reason: "I'm not sure whether a marijuana ban is so good, and my preference for the status quo would have led me to oppose it when it was first suggested; but now that the ban has been enacted, my 'more enforcement is better than less' presumption leads me to support strict enforcement."

[5.] People sometimes also have a "persistence heuristic": Once a goal is set, it's good to be persistent in accomplishing the goal. "If at first you don't succeed, try, try again" is a cliché precisely because it captures a socially valued rule of thumb, helping us overcome our natural tendency to get discouraged. It also affects our evaluation of people: we tend to admire the persistent, and to have some contempt for "quitters," who "never win" (and "winners never quit"). True, people are sometimes seen as wise for not "throwing good money after bad," but there is a general tendency to feel that failure should lead us to redouble our efforts, rather than to give up.

[6.] Persistence and the capacity to inspire persistence are seen as valuable attributes of leadership, so many political leaders may be reluctant to be seen as "giving up" by not aggressively enforcing a law. Sometimes persistence begins to be seen as folly rather than virtue, but generally a leader's willingness to retreat when a law is being flouted tends to be seen as failure, while the willingness to escalate enforcement is seen as admirable.

[7.] Even if the first step's failure suggests that the goal is genuinely unachievable, people may be psychologically and politically unwilling to admit error. Political leaders may hesitate to admit their mistakes, for fear of being discredited; and both voters and legislators may not admit their mistakes even to themselves. People may thus be emotionally and politically more willing to say "Our idea was good, but we just need to increase enforcement a bit" than to say "Getting people to comply will have too many collateral costs, so we might as well just leave the law unenforced."