Are Mormons Christians?

Not for secular courts to judge, holds the Arizona Court of Appeals

From In re Ball v. Ball, decided yesterday by the Arizona Court of Appeals, in an opinion by Judge Paul J. McMurdie, joined by Judge Maria Elena Cruz joined:

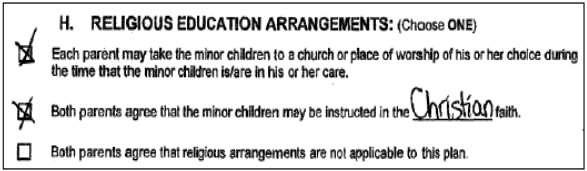

Mother and Father married in November 1999 and have two minor children. In December 2017, Mother petitioned for dissolution. The parties represented themselves during the initial dissolution proceedings, and the court entered a default decree ("Decree"). Filed simultaneously with the Decree was a parenting plan, signed by both parents, that they prepared using a court-provided form ("Parenting Plan"). The court adopted the Parenting Plan's terms as part of the Decree. The Parenting Plan provisions relevant to this appeal are as follows:

Approximately one year after the divorce, Father joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints ("Father's Church"), and the children occasionally joined him at meetings. After Mother learned the children were accompanying Father to his church, she petitioned to enforce the Parenting Plan, claiming Father's Church is not Christian. Mother also asserted other violations of the Parenting Plan.

The superior court held two hearings on the enforcement petition. During the second hearing, Mother called a youth ministry leader from her church to testify that Father's Church is not Christian. After taking the matter under advisement, the superior court held that the Parenting Plan directs that "the Children shall only be instructed in the Christian faith" and that Father's Church was not "Christian" within the meaning of the Parenting Plan. For these reasons, the court held that Father could not take the children to Father's Church's services. The court also found that Father had violated other Parenting Plan provisions and granted Mother an award of attorney's fees….

Father appealed, and the court ruled in his favor. First, it concluded that the parenting plan didn't require the parents to raise their children Christian, but merely allowed it:

The first clause of the religious-education section of the Parenting Plan unambiguously states that "[e]ach parent may take the minor children to a church or place of worship of his or her choice during the time that the minor children is/are in his or her care." This language permits Father to take the children to any "place of worship," be it "Christian" or "non-Christian." Nothing in the second clause explicitly limits or narrows this authority…..

Adopting Mother's assertion that the second clause limits the parents' rights under the first clause would render the first meaningless because the parents could no longer take the children to a church or place of worship of their choice. Instead, the second clause is permissive and ensures that the "children may be instructed in the Christian faith." This interpretation gives effect to both clauses in the Parenting Plan's religious-education section.

But the court went on to add:

Even if the second clause might constrain Father's right under the first clause, we would nonetheless vacate the superior court's holding because the court violated the First Amendment of the United States Constitution when it ruled that Father's Church is not Christian or part of the Christian Faith…..

The Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses of the First Amendment … "preclude civil courts from inquiring into ecclesiastical matters." …. "[E]cclesiastical matters include 'a matter which concerns theological controversy, church discipline, ecclesiastical government, or the conformity of members of the church to the standard of morals required of them.'" …. "[D]epending on the circumstances, civil courts can resolve at least some church-related disputes through neutral principles of law so long as the case is resolved without inquiry into church doctrine or belief."

Here, the court dove into an ecclesiastical matter by addressing whether Father's Church is part of the Christian faith. That very question has long been a matter of theological debate in the United States. A secular court must avoid ruling on such issues to prevent the appearance that government favors one religious view over another.

Moreover, although the question was presented within the context of interpreting the Parenting Plan, the court did not resolve it through neutral principles of law but instead engaged in the exact type of inquiry into church doctrine or belief that the First Amendment prohibits. At the second evidentiary hearing, the court: (1) described the issue as "what is or is not within the definition of Christianity"; (2) allowed Mother to present testimony from a minister from her church claiming that Father's Church was not part of the Christian faith; and (3) admitted into evidence a chart purporting to compare the tenets of Father's Church with Christian beliefs. The court's order specifically found "that Mormonism does not fall within the confines of [the] Christian faith."

Courts are not the appropriate forum to assess whether someone who self-identifies as "Christian" qualifies to use that term. If the superior court's order could stand, the "harm of such a governmental intrusion into religious affairs would be irreparable." "Such a judgment could cause confusion, consternation, and dismay in religious circles." Accordingly, the ecclesiastical-abstention doctrine applies with full force in this case, and we vacate the superior court's order on that basis.

In so holding, we observe that a parenting plan's religious-education provision may be enforced without violating First Amendment principles if the dispute does not require a court to wade into matters of religious debate or dogma….. But parents who wish to address aspects of their children's religious education in a parenting plan should take great care to ensure those provisions are as specific and detailed as possible. Failure to do so may impermissibly entangle the court in religious matters should a dispute ever arise.

This case provides a potent example of this possibility made real. The ambiguities surrounding the phrase "the Christian faith" thrust the court directly into a matter of theological controversy in which it could not take part. Accordingly, we vacate the court's order regarding religious education also because the First Amendment precluded the court from addressing whether Father's Church is part of "the Christian Faith." …

Presiding Judge James B. Morse Jr. specially concurred, concluding that the court shouldn't opine on the constitutional questions.