How Printing Presses Ignited the First Information Revolution

The printing press helped build libraries that were impossibly large by ancient standards. That created its own new challenges.

In The Name of the Rose, Umberto Eco describes a labyrinthine monastic library large enough to lose oneself in. The novelist didn't mention how many books filled its rooms, but John O. Ward of the University of Sydney worked out some straightforward calculations based on Eco's description of the layout and space. The collection, he concluded, would amount to 85,000 volumes.

The library was the "greatest in Christendom," Eco wrote. But actually, it was far, far bigger. It's not uncommon for a modern American public library to contain so many volumes, but no medieval library possessed that number—nowhere close.

Many early monastic libraries could fit their entire collections (probably just a couple of dozen codices) in a niche in the wall or in a single wooden box. As the centuries mounted, so did the stacks. Industrious monks added to the pile every year, but even then we're talking about relatively few volumes. In the sixth and seventh centuries, for instance, monks in the Latin West produced only around 120 books per year—in total. With such low output, libraries of massive size were unimaginable. In Anglo-Saxon Britain, for instance, they rarely exceeded 60 books.

Maybe we should expect small figures. This was, after all, before Charlemagne's education reforms. But if we jump to the Continent a bit later in the ninth century, as the reformers beavered away and book production climbed, inventory evidence for monastic libraries still underwhelms. Saint-Riquier sported just 256 books; St. Gallen, 264; Murbach, 315; and Reichenau, 415. Even the best libraries were poorly endowed. Lorsch shelved 590 books, and Bobbio, one of the most preeminent of all, housed 666. Perhaps an ominous number, but still far short of what Michel de Montaigne—a single individual, not an entire institution—eventually amassed on his own.

As late as the 14th century, one estimate pegs the typical library at 300–400 volumes. "By the end of this period," says Ward, "exceptional libraries were inching over 1,000 titles." The Sorbonne, among the most exceptional, listed 2,066 volumes, though 300 of that total were missing and cataloged as lost; no wonder the 338 books on display were all chained to tables.

Eltjo Buringh and Jan Luiten van Zanden of Utrecht University tally around 5.9 million books produced in all the Latin West from the sixth through the 14th centuries. That's just 7,000 and change per year. That number almost doubled in the 15th century, as humanism took hold and professional copyists started churning out books too; almost 5 million books were added to the total in that century alone. And when printing arrived in the second half of that century, it radically changed the math—along with everything else.

From 1454 through 1500, more than 12 million books were printed, according to Buringh and van Zanden. In the next century, printers pressed out more than 200 million; some estimates float as high as 400 million. Between 300,000 and 400,000 individual works alone hit the market in the 16th century.

"By this art as much is produced in one day by one man even unskilled in letters, as it was barely possible to produce in a whole year by several men with the speediest quill," marveled the Swiss scientist Conrad Gessner. Writing in the mid-16th century, while the eruption of print was still underway, he was awestruck by the presses' prodigious output. The French historian Frédéric Barbier called this explosion of production "a phenomenon of mass mediatization," one never before seen in human history. It had immediate ramifications.

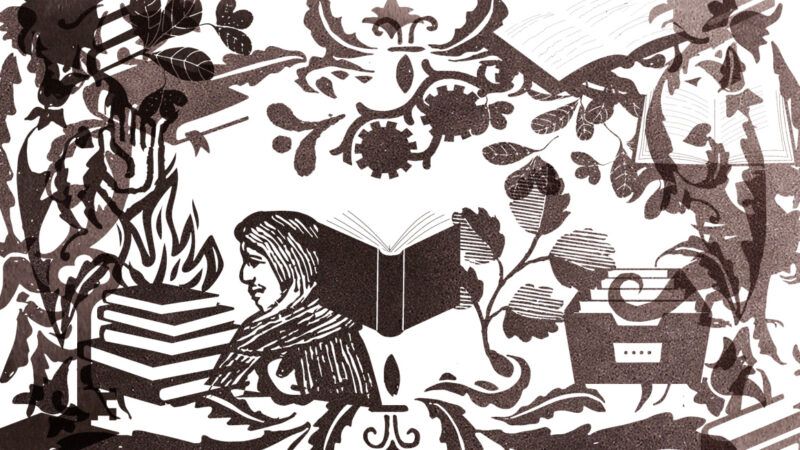

The printing press presented the only way to fill an imaginary monastic library the size of Eco's, but printing would accelerate the trend begun by the humanists and push books well beyond the monastery. Some would seek to support this surge with new organizational structures; some would try to control the ideas it spread; some would destroy whatever they didn't approve. If knowledge is power, printing represented an enormous expansion and redistribution of it.

An Analog Search Engine

Back to Eco's impossible library. Another difficulty is finding anything amid such a gargantuan collection. Montaigne had to concoct homespun solutions for his thousand titles. What about something larger? Without an organizational structure and system for finding desired books or passages within books, "the user must look up and down all the shelves and books and read all the titles," as the 16th century librarian Juan Pérez said. Such a library would be, he said, "a dead library." He said that about a collection not even a fifth the size of the library in The Name of the Rose.

And Pérez assumed that the frustrated library patron at least benefited from bookshelves. But shelves on which books were arranged upright with spines out were a recent invention pioneered by Pérez's own employer, Hernando Colón, the bastard son of Christopher Columbus. Eco set his tale in the 14th century, when librarians primarily stored their books in chests and arrayed them in stacks on benches or tables, making for tedious hunting. The situation was largely the same a century later.

When the poet Antonio de Tomeis visited the Vatican library in 1477, he saw "sixteen chests / Full of books." Those were topped with stacks of additional books, chained to ensure that they didn't wander off. If we assume 100 books per chest and a few dozen atop them, we're talking about a library—the library at the nerve center of the Catholic Church—of just a couple of thousand books. But shuffling through them all was still grueling. When finished, Tomeis was "so exhausted and overwhelmed" that he had to "sit down, breathless."

By 1477, Tomeis was only a quarter-century into the print revolution. Imagine the job with twice, thrice, or 10 times as many books. Imagine doing it with the 85,000 supposedly in Eco's monastic library!

Large numbers of books have always presented difficulties for finding the helpful bits. Librarians in the ancient Middle East inscribed clay tablets with metadata such as a work's genre and incipit (the first few words of a text, usually to serve as a title). In Alexandria, librarians created a vast, information-dense, alphabetical catalog to navigate their holdings. Medieval scholars used and developed these and other techniques, employing both commonplace books—compilations of choice selections from existing works—and indexes.

These ancient and medieval tools would be adapted for the age of print. No one developed the search apparatus of the library more spectacularly than did Pérez's boss, Colón.

Enamored of the possibilities of print, Colón sought to amass a universal library. By the time of his death in 1539, he had collected more than 15,000 books in various languages—an astonishing number for the time—not to mention countless boxes of pamphlets, posters, and print ephemera that most regarded as worthless. Displaying the collection in his library in Spain, Colón aspired to construct the greatest idea machine ever built, featuring not only the best thinking of the human race but also its most diverse manifestation to date. But how to organize such a monstrosity?

Tired of rummaging through boxes of books or shuffling among the stacks atop benches, Colón championed the use of bookshelves with upright books, aligned and readable in rows, the way we organize books to this day. But his bigger advances lay in developing an analog network of hypertexts and hyperlinks that helped users navigate his collection, his Libro de los Epítomes ("Book of Summaries") and Libro de las Materias ("Book of Subjects"), each stretching to multiple volumes.

With so many books to explore and limited hours to employ, readers needed a means of deciding whether this or that book warranted perusal. Since a title might be insufficient or misleading, the Epítomes summarized books' contents, allowing a reader to get a sense of the subject matter and even, in many cases, details of the author's biography and style. These summaries were cross-referenced with other catalogs Colón developed, essentially creating hyperlinks between volumes, a feature he developed even further in the Materias.

While a reader could beneficially browse the Epítomes at random, the real gains were for researchers or buyers who wanted distillations of books they were already curious about. But what if someone wondered about a certain topic and needed to know where to look for more? Robert Grosseteste and Hugh of Saint-Cher had addressed those challenges with indexes that reached both across and within volumes to carve up knowledge into discrete conceptual packets that could be consulted as curiosity nudged. Colón expanded this tradition.

Colón had already added personalized indexes to certain books in his collection. Now he began creating an index that encompassed and cataloged the entire library—not just the broad subject matter of its books, but all the individual topics covered within each, whether at length or in passing. That way, a person wanting to gin up a homily, a humanist oration, or a scientific treatise could work with whatever sources the library had to offer.

Working with the Materias, the researcher could follow the trail of a subject through history, philosophy, theology, poetry, the Bible, whatever, freely across such categorical distinctions as author, book, and genre, a freedom that enriched the resultant research. "The Libro de las Materias created a network of connections between the words in the library," explain José María Pérez Fernández and Edward Wilson-Lee in Hernando Colón's New World of Books. Suddenly, the overwhelming ubiquity of books became not a burden but a benefit, as the index could help the reader find the choice bits he desired while encouraging serendipity along the way.

But while Colón and scholars like him reveled in the challenges brought on by the flood of print, others fretted over what all those new books said. And indexes could be put to less scholarly and liberal ends than Colón ever imagined.

Silly, Useless, Idle, and Worse

Consider the Swiss scientist Gessner. He embraced the humanist project of recovering and preserving classical works, envisioning a Library of Universal Knowledge. Unlike Colón, he didn't try to assemble this himself, book by book. Instead, he hustled three years building an elaborate, annotated, alphabetical bibliography listing every known book in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, including those long lost. The resulting tome, the Bibliotheca Universalis, totaled 1,300 large pages and featured around 10,000 works by about 3,000 authors.

In some ways, Gessner's project mirrored Colón's, all the more so when three years later he produced his Pandectarum, a huge index to the Bibliotheca Universalis. Together the books would give librarians a catalog they could modify with call numbers for their own shelves, an acquisitions list when funds were available, and means for scholars to find needles in haystacks. Gessner saw a partnership between printers and librarians as a powerful tool for preserving his beloved classics.

But only those. Gessner fretted over the inflow of lowbrow literature. "Although the typographical art seems to have been born for the conservation of books," he said in 1545, "most of the time nonetheless the silliness and useless writings of the men of our time are edited, to the neglect of the old and better ones."

With so many books available and more coming by the day, many scholars shared this opinion. Several decades later, when Thomas Bodley started rebuilding the library at Oxford, he was choosy about what landed on his shelves. There would, he said, be no "idle books and riffe raffes," such as, say, Shakespeare—or any other books in English. Bodley wanted only books in the classical and biblical languages.

Others fretted less over language than over ideas. With the simultaneous rise of printing and the Protestant Reformation, people treated books and their contents like a battleground. What none of the participants appreciated at the time was that the very forces driving the conflict made it impossible to contain.

Word Wars

Martin Luther's final break with Rome came in 1520, when he torched the papal bull that condemned him and his teaching. Supporters gathering for the protest also chucked Catholic pamphlets and books of canon law onto the pyre. These moves set a pattern.

When anti-Catholic German peasants rose up in 1524, their first targets included monasteries; since monks were heavily involved in book production, the peasants singled out libraries for destruction. After one Cistercian monastery in Herrenalb was ravaged, no one could enter the ruins without finding shredded, dismembered books underfoot. Some monasteries lost thousands of books, their shelves having been swollen by the recent arrival of print. Easy come, easy go.

In England, the theft of monastic holdings was a formalized process sanctioned by the government. After the Act of Supremacy in 1534, monasteries were dissolved and their property—including books—seized. The gentry and merchants bought up the assets and disposed of them however they saw fit. Collectors valued some of the books, but countless treasures ended up destroyed, used in some cases to rebind other books, clean boots, polish candlesticks, and serve even lesser ends. Some found their way to lavatories, recycled one scratchy page at a time.

The ravages continued as the Reformation progressed. It became illegal in England to own Catholic books. Cambridge and Oxford saw their shelves picked clean of Catholic books during Edward VI's reign—and then of Protestant books during the reign of the Catholic monarch Mary Tudor.

In the Netherlands, Catholics raided printers and bookshops, tossing their wares on pyres and sending them up in smoke. Indexes of prohibited books began proliferating across Europe in the mid–16th century, empowering authorities to scour, purge, burn, and deface books by not only Protestants but humanists, Jews, Muslims, misbehaving or misbelieving Catholics, and otherwise heterodox authors.

In 1526, for instance, England's Henry VIII published a list of forbidden books. There were only 18 titles on the original list, three times as many books as Henry had wives. Arguably, he disliked the books even more than his unlucky spouses; after three years, he expanded the list to 85 titles.

Francis I of France followed suit. In 1544, he authorized theologians at the University of Paris to publish a list of heretical books, corrected and expanded every few years afterward. Book banners employed the same bibliographic techniques developed by Colón and Gessner but now to the opposite end, not to broaden but to restrict access and use. "Each edition's contents were arranged alphabetically, by last name of author, in two sections divided by language," reports the historian Robin Vose, "the first being entirely devoted to Latin works, followed by another in French (with some Italian as well)." Another section of the Paris index listed anonymous books alphabetically by title and language. In 1551, the Spanish Inquisition used a similar list from the University of Leuven to create an index employed in persecuting heretics.

By the mid-1550s, most Catholic regions possessed one or more such indexes, none of whose contents exactly matched. With the accession of Pope Paul IV, there came a single, authoritative list (the Vatican's official Index of Prohibited Books) and a centralized body to exercise regulatory authority (the Congregation of the Index). Who ended up on the naughty list? Protestant Reformers, naturally—Luther, Martin Bucer, John Calvin, Huldrych Zwingli, and others—but also everyone from Daniel Defoe to Denis Diderot.

Maddeningly, the Index offered no specific reasons for inclusion on the list. An author was merely listed or not. On the other hand, inclusion could enhance an author's fame or appeal, particularly in Protestant countries. In 1627, Bodley's successor at Oxford, Thomas James, secured a copy of the Index, reprinted it, and encouraged librarians to use it as a theological buy guide.

If discovered, listed books might be burned or, if only marginally offensive, redacted or otherwise purged of problematic passages by scribbling them out, painting them over, or tearing out pages. One section of a 1541 copy of Erasmus' Adages "was treated with particular disdain," writes Owen Jarus of Live Science, "having pages ripped out, sections inked out and two of the pages actually glued together." When the censors "corrected" Giovanni Boccaccio's humanist masterpiece The Decameron, widely loved for its language, craft, and inventiveness, they left its obscene parts untouched and instead edited the bits that made clergy look bad. The censors could be brutal too: The authorities seized the Venetian book smugglers Pietro Longho and Girolamo Donzellini, trussed them up, and drowned them at sea.

But whether doctoring individual copies, bowdlerizing new editions for print, or punishing scofflaws, the censors couldn't keep pace with the printers. Remember: Printers produced between 300,000 and 400,000 individual works in the 16th century alone, tallying between 200 million and 400 million copies. The idea that the authorities could read everything produced, let alone scribble out individual lines, is laughable.

The Index of Prohibited Books was a medieval answer to a modern problem and failed to meet the challenge. Instead, the explosion of books and literacy occasioned by the printing press was about to reshape the world.

This essay is adapted from The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future by permission of Prometheus Books.