How Opioid Settlement Money Turned Into a $600K Party Fund

Cities and states promised to use opioid settlement money to fight addiction. Instead, they’re spending it on concerts, police cars, and political perks.

The town of Irvington in Essex County, New Jersey, was hit hard by the opioid crisis. In 2023, the county recorded 459 drug overdose deaths, 401 of them opioid-related—the most deaths of any county in the state. Despite this predicament, Irvington officials spent most of their more than $1 million share of opioid settlement funds not on treatment, prevention, or recovery programs, but on a pair of summer concerts with DJs, luxury trailers, and catered food.

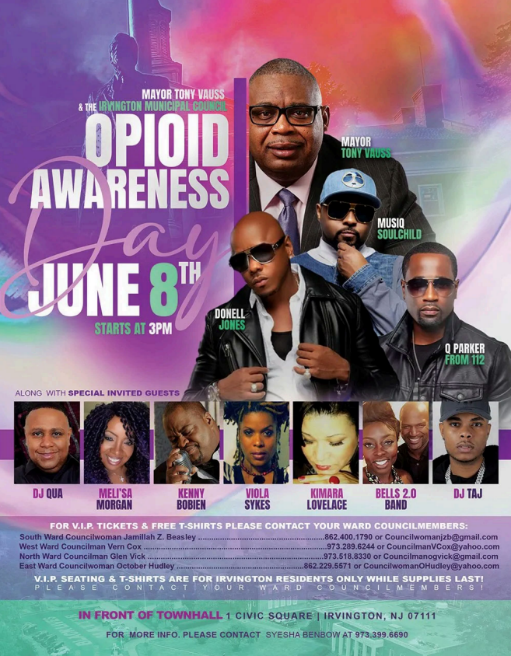

The town billed the concerts as "Opioid Awareness Day," but they appeared designed more to promote awareness of Mayor Tony Vauss. His name topped the event's promotional materials, and, as the State Comptroller later noted, "no opioid-related information appeared on stage, though two large posters of Mayor Vauss flanked it."

Those two concerts cost the township more than $630,000, according to the comptroller's investigation, with much of that money going to Antoine Richardson, a DJ who was put on Irvington's payroll following Vauss' election in 2014. Richardson already drew an annual salary of nearly $180,000, plus full benefits, for a job called "Keyboarding Clerk 1" with no set hours. The investigation revealed that businesses owned by Richardson's immediate family collected about $370,000 in related contracts for the concerts.

Beyond a few opioid-related "pamphlets printed from the internet" and a small table stocked with a handful of Narcan, the investigation found that there was virtually no health programming. Richardson told investigators that before his DJ set, he told the crowd to "stay clean" and "say no to drugs"—and that each performing artist said something to the effect of, "Kids, stay in school, stay away from drugs."

Irvington, New Jersey, is not an isolated case. Across the country, state and local governments are receiving approximately $50 billion in the next decade from settlements with opioid manufacturers, distributors, and retailers—including Johnson & Johnson, CVS, and Walmart—to remediate the overdose crisis.

The settlements offered governments significant discretion in how to spend the money. Exhibit E of the national agreement lays out a non-exhaustive list of recommended uses—such as expanding treatment access, supporting harm reduction programs, and improving data collection—but leaves enforcement entirely up to the states. The settlements do not stipulate formal penalties for misuse; there are no clawback provisions or reporting requirements in place.

States were required to draft a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with their municipalities, outlining how funds are allocated and specifying any reporting requirements. New Jersey's MOA and state law require expenditures to be "evidence-based" or "evidence-informed," which is what led to the city of Irvington's trouble. Whether any of that money will be recovered—or whether officials will face consequences—remains to be seen.

Elsewhere, misuse has taken subtler forms. In Indiana's Scott County, settlement dollars were used to pay staff salaries, freeing up local funds for other priorities. In West Virginia, more than half of all settlement spending last year went toward police vehicles, jail bills, and salaries, while only six percent supported treatment and recovery. These practices, known as supplantation, enable local governments to use new money to replace existing funds, effectively turning settlement dollars into general revenue.

The pattern mirrors the infamous failure of the 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement. According to a Government Accountability Office report, states received more than $50 billion from tobacco companies between 2000 and 2005, but only 30 percent went to health care and smoking prevention. The rest was absorbed into state budgets, debt service, and infrastructure projects.

Some states even securitized their future settlement payments, trading decades of public health funding for an upfront lump sum, and forfeiting long-term funding streams that could sustain treatment and prevention infrastructure in exchange for short-term priorities. The same practice is already being discussed for opioid settlements.

When governments are entrusted with funds to address a crisis that has claimed more than 800,000 lives since 1999, they carry a moral obligation to act accordingly. Every dollar wasted is a dollar not spent on expanding access to treatment, distributing naloxone, or building recovery infrastructure. The outcomes of the tobacco settlement provide clear lessons for the use of opioid settlement funds: Absent binding guardrails and rigorous transparency, both state and local governments face strong incentives to divert or front-load funds in ways that undermine their intended purpose.