Why Is It So Hard for Congress To End a War?

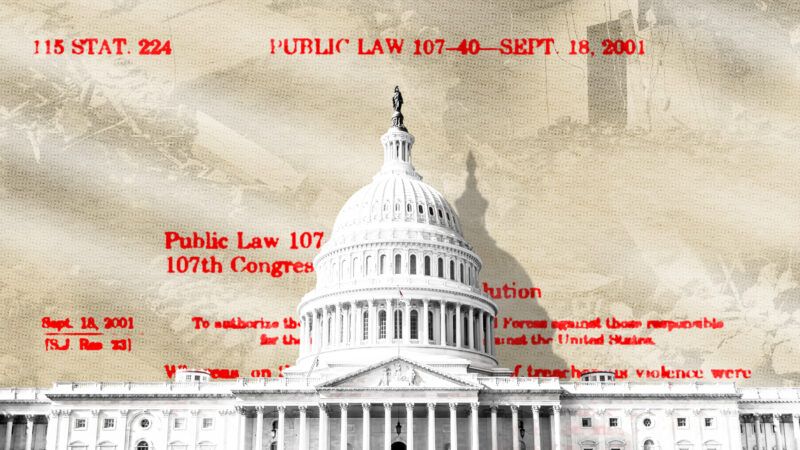

Lawmakers are once again trying to reclaim their war powers through AUMF repeal.

March will mark 20 years since the United States launched its invasion of Iraq, and with it a wave of catastrophic choices that continue to plague American foreign policy. It took a little over a month for President George W. Bush to declare victory over Saddam Hussein's forces and announce the continuation of a reconstruction mission.

But the end of the war wasn't really the end of the war. That's true in the context of Iraq, where the U.S. occupation helped exacerbate violence and instability for nearly nine years post-Saddam. It was true procedurally, too; to this day, Congress has not repealed the authorization it passed to allow the president to invade Iraq in 2003.

On Thursday, lawmakers in the House and the Senate introduced a bill to roll back that measure, the 2002 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), as well as the 1991 AUMF, which authorized U.S. participation in the Gulf War. "The 1991 and 2002 AUMFs are no longer necessary, serve no operational purpose, and run the risk of potential misuse," said Sen. Tim Kaine (D–Va.), one of the bill's sponsors. Sen. Todd Young (R–Ind.), another sponsor, added that "Congress must do its job and take seriously the decision to not just commit America to war, but to affirmatively say that we are no longer at war."

This isn't the first time lawmakers have tried to roll back AUMFs. But efforts to repeal the 1991 and 2002 AUMFs—as well as the never-used 1957 AUMF, which authorized action against communist threats in the Middle East, and the constantly used 2001 AUMF, which authorized action against any party involved in the 9/11 attacks—have never made it all the way. It's proven easy for Congress to give up its war powers; it's been much harder for it to reclaim them.

AUMFs allow the president to take military action without first asking Congress, which is the sole body allowed to declare war according to the Constitution. Congress hasn't formally declared war in over 80 years. Worse still, it's passed laws giving the president more discretion in military conduct, insisting less on proper oversight. AUMFs have served as blank checks that shield the president from accountability for military adventurism.

The threats that motivated those emergency powers in the first place are largely gone. The Gulf War is long over, Saddam Hussein is long dead, and there is no longer a Soviet Union looking to wreak communist havoc in the Middle East. Still, repeal efforts have always stalled.

For lawmakers, repealing the 1991 and 2002 AUMFs should be a political slam dunk. Neither AUMF is the sole statutory basis for any current U.S. military action (and the 1991 AUMF hasn't even been used since the Gulf War). Even if lawmakers are reluctant to engage in broader debates over congressional war powers and presidential overreach in conflicts, repealing the toothless AUMFs makes it look like they're tackling those issues.

The measures remain on the books, though, ripe for potential abuse. Presidents have used the 2001 AUMF's broad phrasing to justify military operations in at least 19 countries. Given this AUMF's ongoing usage, lawmakers have been far less willing to tackle it than they have others. The 2002 AUMF has had a much smaller footprint, and it hasn't been the sole authorization behind any military action since the Iraq War ended in 2011.

AUMFs have diluted Congress' own say in American foreign policy by reallocating so much war-making power to the president. But some lawmakers are still trying to give up more. Last May, former Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R–Ill.) introduced AUMF legislation that would've allowed the president to send U.S. troops to Ukraine. And in January, Reps. Dan Crenshaw (R–Texas) and Mike Waltz (R–Fla.) introduced an AUMF that would've allowed the president to use military force against Mexican drug cartels.

Even as some lawmakers attempt to formally end wars, their colleagues are pushing for the president's power to enter new ones. It's ultimately the American people who lose when it's no longer a requirement for the president to make his case for military force and face the political costs that follow.