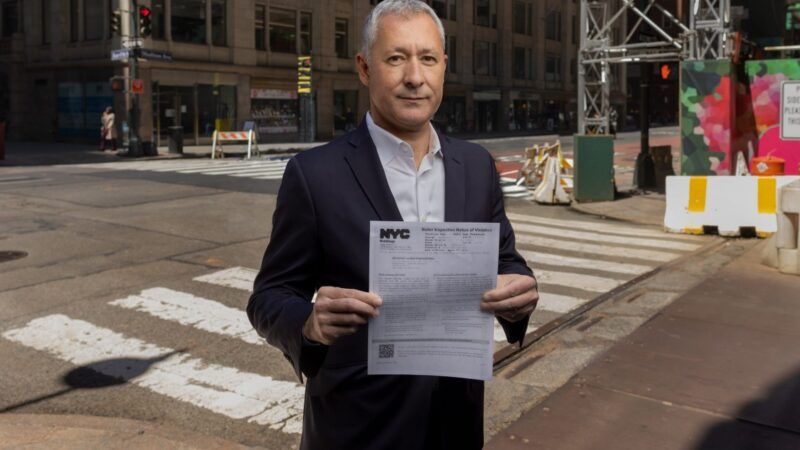

He Didn't Break Any Rules. New York City Is Demanding He Pay a Fine Anyway

The Big Apple's building regulations are almost impossible to navigate, and officials like it that way.

People should be horrified to learn that Serafim Katergaris, a New York City resident, was forced to pay a fine to the city for a code violation he not only didn't commit but had no way of knowing about. But while Katergaris has the means to fight grasping city officials and may ultimately win in court, his Kafkaesque ordeal is no isolated incident. The city's building regulations have long been used to victimize the innocent and to fill government coffers while also lining the pockets of city officials.

"Serafim Katergaris was forced to pay $1,000 to the New York Department of Buildings (DOB) for a code violation he did not commit, did not know about and had no chance to challenge," notes the Institute for Justice (IJ), which is representing the Harlem property owner. "New York City requires property owners with certain kinds of boilers to have their boilers inspected annually and then file a report with the city regarding the inspection. When Serafim bought a home in Harlem in 2014, it did not have a boiler. The previous owner had removed it earlier that year, with the necessary permits and documentation filed with the DOB post-removal. However, the previous owner did not file an inspection report the year before he removed the boiler—something Serafim did not know because the DOB did not assess the violation until after he had purchased the property."

City officials wouldn't even allow Katergaris to argue that he shouldn't be held accountable for a paperwork violation on a boiler he had never owned or even seen. They allowed no appeal of the alleged violation and fine. His response was to cough up the money to allow the pending sale of the property to a new owner to proceed, and to file suit against the city in federal court.

That byzantine code requirements and resulting penalties are common in New York City is obvious from the fact that IJ also represents Queens resident Joe Corsini in a separate lawsuit over rules enforcement around a pigeon coop. And it's not difficult to find yet more examples of unjust enforcement that seem designed to harass and impose unnecessary expense.

"Some of the toughest punishments have had less to do with property owners' flouting safety rules than with their confusion over how to respond to that first ticket. Any delay or misstep can lead to a series of fines that will snowball until the owner certifies that the violation has been set right," The New York Times reported in 2019. "For nearly a decade, a majority of those fines have been imposed not on mega-landlords caught harassing tenants with construction, or developers whose inattention contributes to worker deaths, but owners of one- to four-family homes who are unfamiliar with the intricacies of the building code."

Notably, inspectors are a lot more diligent about ticketing people than they are about determining if there's any actual violation.

"Inspectors did not always wait to gain access to properties before issuing failure-to-comply tickets," the Times added. "They simply posted new tickets on the door if owners weren't home."

This can partly be explained by sheer bureaucratic dickishness on the part of lazy government workers offended that the world doesn't operate at their convenience. But the hard-to-navigate rules are also a money-making opportunity for inspectors who demand bribes to look the other way. Last year, the office of the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York announced a guilty plea on the part of Francesco Ginestri, who "admits to selling his position as a building inspector in exchange for cash." Four years earlier, 16 building inspectors were arrested in a single case for accepting $450,000 in payoffs.

"The 26 indictments filed by Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. lay out a stunning portrait of greed in which developers bought off inspectors to overlook code violations and speed their developments to completion," noted the New York Daily News.

How do people know which officials are on the take and how much to pay them? Mostly, they don't—they hire somebody who does the job for them. Among those arrested in 2015 were "expediters," a breed of middlemen who navigate the building codes for builders, contractors, and property owners.

"Filing a permit may sound simple but very basic mistakes can cost you time and money," Brick Underground, a real estate publication, helpfully explained earlier this year. "An expeditor is someone who can handle the filing process for you."

"To navigate the agency's bureaucratic swamp, developers have for years paid 'expediters' to speed their projects to approval—getting permits faster, addressing violations and filling out key paperwork," observed the Daily News in 2015. "It's an arrangement critics have long slammed as corrupt."

The thick and seemingly unknowable tangle of regulations in New York City that ensnared Katergaris not only remains in place, but worsens, year after year because so many people profit from the bureaucratic maze. The rules are not supposed to be reasonable or navigable in any way. The building codes are designed to be insurmountable for anybody who doesn't give city officials what they want. And, more often than not, what they want is to be bribed.

Ultimately, Katergaris may prevail and convince a federal court to require the simple justice that New York City officials refuse to afford their long-suffering subjects.

"The Due Process Clause of the United States Constitution guarantees everyone a right to fair notice and an opportunity to be heard in front of an impartial tribunal before the government can impose a punishment," according to IJ. "[Katergaris] has asked the court to declare that unreviewable fines are unconstitutional and order DOB to afford people their right to be heard as due process requires."

But even that will only be a partial victory. While allowing appeals of fines issued for what are often petty violations or errors of judgment on the part of inspectors will certainly somewhat ease the ordeal inherent in dealing with New York City's regulations, it won't alter the existence of rules that are unreasonable and corrupt to their core. Fully addressing the real injustice of New York City's building codes and similar regulations elsewhere requires getting past the idea that they have any legitimacy.

Once people realize that arcane red tape is often intended not to make the world a better place, but to extract compliance and money from the public, they might be more willing to push back. The real victory will come when Katergaris and everybody else who owns property can buy, sell, perform maintenance, and customize what they own to their taste without worrying about regulatory boobytraps and greasing officials' palms.