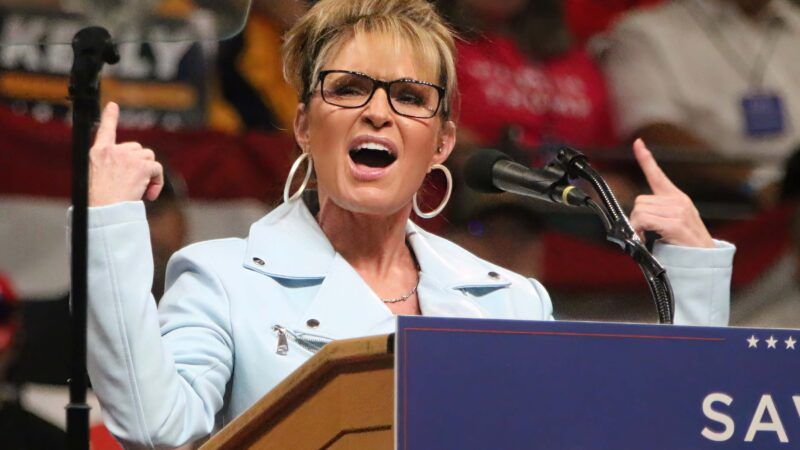

Don't Blame Ranked Choice Voting. Sarah Palin Was a Bad Candidate.

Blaming the ballot system ignores the fact that many Alaskans simply did not think the former governor really represented them.

In a stunning upset last week, Democrat Mary Peltola defeated former Republican Gov. Sarah Palin in a special election for Alaska's sole congressional district. The race garnered a lot of attention for its use of ranked choice voting. In 2020, Alaskans approved the new system, which allows voters to rank each candidate by preference. If no candidate wins an outright majority, then the lowest-performing candidate is eliminated and his or her voters' ballots are tallied again, with the second choices counted first instead. This repeats until a candidate passes 50 percent.

After the first ballot, Palin trailed Peltola 40–31, with Nick Begich III in third with 29 percent. After Begich was eliminated and his ballots were re-tallied, Peltola prevailed over Palin 51–49.

In the days after Palin's loss, prominent conservatives and Republicans criticized the new system for contributing to her defeat. After the results were announced, Sen. Tom Cotton (R–Ark.) tweeted, "Ranked-choice voting is a scam to rig elections." (Previously, he has referred to it as a "radical scheme.") Palin herself called the system an "experiment" that's "crazy, convoluted," and "confusing." In National Review, Jim Geraghty termed it "a legitimate electoral system…that doesn't make sense."

But it's not ranked choice voting's fault; Palin was simply a bad candidate.

Geraghty complained that ranked choice voting was "more complicated" than "the familiar 'first past the post' system," that "the Democrats came out the big winner, even though their candidate finished fourth in the first round of voting." This is true, though the third-place finalist, Al Gross, withdrew from the race after the June primary and encouraged his voters to support Peltola.

Cotton complained that even though "60% of Alaska voters voted for a Republican…a Democrat 'won.'" This is also true, though notably they did not all vote for the same Republican. Begich and Palin collectively accounted for 59.8 percent of the first-round vote, but only about half of Begich's voters chose Palin as their second choice; nearly 30 percent picked Peltola, while 21 percent did not choose a second or third choice.

Under a traditional primary system, Palin likely would have beaten Begich in a Republican primary and faced Peltola one-on-one. But Begich's voters would not necessarily have then turned out for Palin—in fact, they had the opportunity to do so on the ranked-choice ballot, and more than half chose not to. Far from being some radically convoluted "scheme," the most direct effect of ranked choice voting is to serve as an "instant runoff" by letting voters indicate which candidates they would prefer if their first or second choice didn't win.

Many of these complaints elide Palin's actual quality as a candidate. Many Alaskan Republicans were skeptical of her, as was reported by The Washington Post in April when she filed to run. Throughout the campaign, Palin criticized the ranked choice voting system, telling the crowd at last month's Conservative Political Action Conference in Texas, "It's bizarre, it's convoluted, it's confusing and it results in voter suppression…It results in a lack of voter enthusiasm because it's so weird." But as Geraghty noted, 85 percent of Alaskan voters polled by Alaskans for Better Elections found the new system either "somewhat simple" or "very simple."

Ranked choice voting is not a "scheme to rig our elections" by "out-of-state liberal billionaires," as Cotton has alleged. But as Geraghty correctly pointed out, it is also not a panacea for every issue in the current political duopoly. It is merely an alternative that gives voters more options than simply one Republican versus one Democrat. And as with any electoral system, a candidate still needs to convince voters to turn out for them.