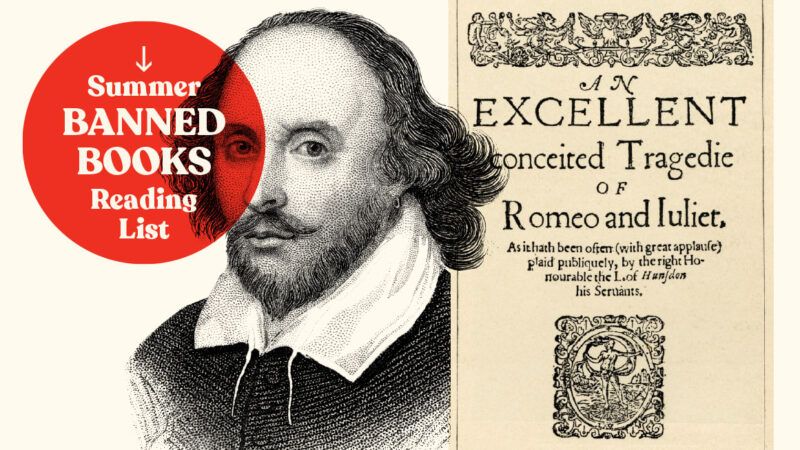

Read the Real Romeo and Juliet, Not the Kid-Friendly Version

Though book banners may try to convince otherwise, students don't need protection from the passion portrayed in Shakespeare's classic.

In ninth grade, like high school freshmen all over America, I was assigned Romeo and Juliet to read for my English class. As a longtime literature geek even at the age of 14, I was thrilled to be entering the big leagues. We'd read some Charles Dickens and a little John Steinbeck. But this? This was William Shakespeare. This was serious, complicated stuff.

You'll have to imagine my excitement as I took the book home to show it to my father, a professor of American literature. The look of irritation on his face as I passed him the book is something I'll never forget.

We had been given a textbook version of Romeo and Juliet—an expurgated, shortened, made-appropriate-for-schoolchildren version. Some pettifoggers had decided that the play's boisterous sexuality, raunchy puns, and panting young lovers needed to be toned down for the students who would be reading it.

As my father pointed out, cutting all that material renders the play exceptionally dull and, in some places, barely comprehensible. Mercutio, for example, could barely appear at all in such a version. That turns his death into a minor side plot rather than a tragedy that spurs much of the play's violence.

Romeo and Juliet is a story driven by passion, in all its sexual, physical, and "embodied" aspects. It revels in jokes about blood and maidenhood, in puns about how soon Romeo will be "coming" to Juliet, and in a balcony scene that scales the height of love poetry but is unafraid to have Romeo plaintively ask Juliet (in tones familiar to many high school students), "O, wilt thou leave me so unsatisfied?" The play takes us from the dream of love to its physical realities and then to its tragedies. That is its strength. That is why we still read it more than 400 years later. And that is not something from which students need protection.

I was lucky. My dad promptly handed me his Riverside edition of Shakespeare's plays, told me to read the "real thing," and said I should come see him if I had any questions about what I read. I learned to love Shakespeare for the beauty and the bawdiness of his work. I never found him dull or hard to understand, because my dad made sure I got the real thing. I can draw a direct line from that parenting choice to nearly every academic decision I have made since.