Not Everything Is a National Emergency

If the National Emergencies Act goes without reform, presidents will continue to misuse emergency declarations as leverage to shift Congress.

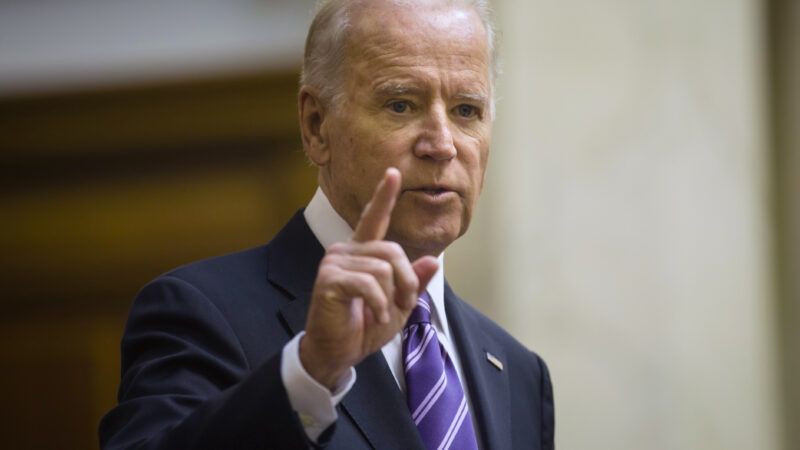

"Action on climate change and clean energy remains more urgent than ever," President Joe Biden said Friday after Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) rejected his own party's climate legislation. "So let me be clear: if the Senate will not move to tackle the climate crisis and strengthen our domestic clean energy industry, I will take strong executive action to meet this moment."

Monday night, citing three unnamed sources, The Washington Post broke the story of what that action may be: "Biden is considering declaring a national climate emergency," the paper reported, and it could happen "as soon as this week." Activists believe a national emergency would let Biden "halt crude oil exports, limit oil and gas drilling in federal waters, and direct agencies including the Federal Emergency Management Agency to boost renewable-energy sources," the Post notes. Though political realities—especially high gas prices and inflation—and the inevitable Republican-led lawsuits may serve as some restraint on Biden, the activists are correct that emergency declarations are a potent boost to presidential power.

And that's exactly the problem. Emergency declarations have become a lazy political workaround, a way for presidents to bypass Congress after it fails to do its job—or, in some cases, outright rejects what the president wants. National emergencies have become a loophole to administrative lawlessness, and they are in dire need of reform.

In their present form, emergencies are governed by the National Emergencies Act of 1976. Presidents from Jimmy Carter onward have declared 75 emergencies citing the authority of that law, and about half of those declarations, many now decades old, remain in effect today. Some of them address situations (the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, for example) that may fairly be described as national emergencies. Others plainly do not, like those sanctioning people undermining democracy in Zimbabwe and Belarus, two emergencies initially declared during the George W. Bush administration and re-upped by Biden. However bad these situations are for the people of Zimbabwe and Belarus, they are not national emergencies for the United States, and Congress could have acted on these circumstances if it so chose.

Climate change is more obviously of import to our country and may well be an emergency in a colloquial sense. But as far as its legal status goes, the phrasing of Biden's threat gives the game away: If the Senate will not move, he says, the administration will act instead. But the very point of an emergency declaration is that it permits the federal government to act when Congress does not have time to move. Congress has had a year and a half of Democratic trifecta governance to move on climate change and has not done so as Biden desires. Yes, that is mainly Manchin's fault—to his Democratic colleagues' great frustration. Alas for them, Manchin is part of Congress, and the problem here simply is not lack of congressional opportunity to act.

"An 'emergency' does not elicit endless debate without consensus, nor is it addressed with a plan requiring years to execute," as former Libertarian Rep. Justin Amash has argued. "A house is burning, a ship is sinking, a city is flooding—these are considered emergencies precisely because everyone agrees they require immediate action."

National emergency declarations are not for when a senator won't vote the way the president wants. They are not tools of presidential blackmail to make the legislature do the executive's bidding. For all its demonstrated openness to presidential abuse, the purpose of the National Emergencies Act was not to completely invert the Constitution's design for the flow of federal action. Unfortunately, recent presidents have realized how emergency declarations might be used to that end.

Biden's attempt to strong-arm the Senate on climate change is remarkably reminiscent of former President Donald Trump's 2019 threat to declare a national emergency so he could get funding to build his much-promised border wall. Trump might "think that Congress's repeated failure to provide funds shows the need for emergency action," Elizabeth Goitein of the Brennan Center for Justice wrote in The Atlantic. "The truth is the exact opposite. By giving Congress time to definitively establish its unwillingness to fund the border wall, Trump is both taking away any legitimate justification for emergency action and proving his intent to subvert the constitutional balance of powers." Swap out a few words and the same critique applies to Biden and climate change.

So long as the National Emergencies Act goes without reform, presidents will continue to misuse emergency declarations as leverage to shift Congress, as Trump and Biden have done. The law should be changed to strictly limit why and for how long national emergencies can be declared and to more carefully define the scope and nature of the problems these declarations can address as well as how long the state of emergency can continue without congressional endorsement of the president's plan. That time limit should be quite short—a few days, perhaps, instead of the current six months—so lawmakers are forced to consider emergency actions on their own merits rather than rubber stamping entrenched federal programs. If it's really an emergency, even our legislators should be able to get themselves together to act.