No, Elon Musk Didn't Pay a 3.27 Percent Tax Rate

Plus: How misinformation spreads, ignoring inflation, and more...

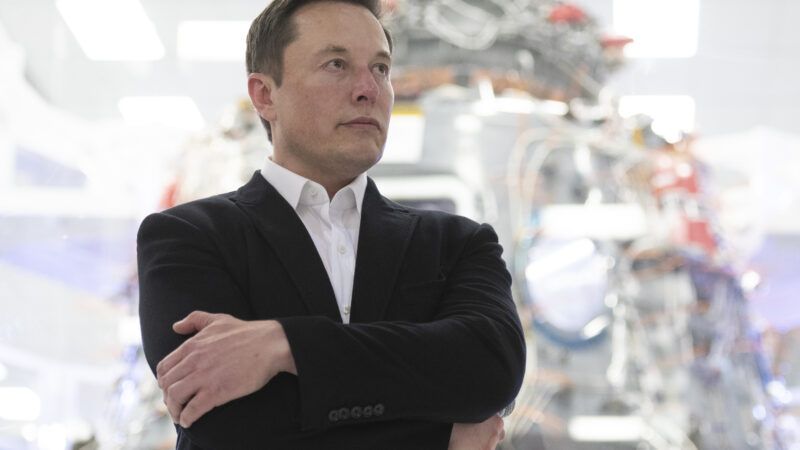

"Musk paid an effective tax rate of 3.27%" claims Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D–Wash.). Politicians love to lament misinformation and disinformation on social media…but they seem to make an exception for themselves. The latest case in point comes from Democrats' rhetoric around taxes paid by Elon Musk.

The Tesla and SpaceX CEO recently became progressive enemy of the week after striking a deal to buy Twitter and promising to institute—gasp—policies more friendly to free speech. Musk's move has spawned a whole host of weird freakouts and demands, including insistence that Musk owning Twitter means we must reform Section 230 (the federal law that helps shield digital platforms from some legal liabilities for user content) and that it will help Donald Trump win the presidency in 2024. Along with this hysteria has come all sorts of Musk criticism and attacks that are occasionally justified but largely divorced from reality.

This includes some seriously skewed information about Musk's tax burden. On Monday, Jayapal tweeted: "Just a reminder that from 2014-2018, Elon Musk paid an effective tax rate of 3.27%. The average working family pays an average tax rate of 13%. It's time for a wealth tax in this country."

The implication here is that Musk isn't paying his fair share in taxes and, conveniently, it lends itself to a popular progressives talking point about taxing wealth.

But Musk is already paying a massive sum of money in taxes—somewhere in the range of $8 billion to $15 billion for 2021, according to estimates from various media sources. "I will pay more taxes than any American in history this year," Musk tweeted last December.

Musk's income puts him in the top federal income-tax bracket, where income is currently taxed at 37 percent.

According to ProPublica, Musk's average effective federal income tax rate between 2013 and 2018 was 27 percent.

And the tax on exercising his Tesla stock options was much higher. "Since the options are taxed as an employee benefit or compensation, they will be taxed at top ordinary-income levels, or 37% plus the 3.8% net investment tax," notes CNBC. "He will also have to pay the 13.3% top tax rate in California since the options were granted and mostly earned while he was a California tax resident. Combined, the state and federal tax rate will be 54.1%."

Jayapal seems to have reached her "alternative facts" (to use a vintage Trump-administration term) by calculating Musk's tax rate based on a system she wishes we used rather than the calculation system we actually use.

As it stands, Americans do not pay taxes on unrealized gains—that is, appreciations in investments that exist only on paper. If you own a stock worth $5 per share and its worth increases to $6 per share over the course of a tax year, you have an unrealized gain of $1 per share. You aren't expected to pay taxes on that gain until you sell your shares—which makes sense, since 1) you don't actually have that money yet and 2) the stock's worth could drop again before you sell. Maybe next year the stock decreases to $4 per share.

No, he paid 27% of his income in taxes from 2013-2018 (Source: stolen ProPublica data). You only get 3% if you include unrealized capital gains https://t.co/93D9RnSyMI

— Jeremy 'adjusted for inflation' Horpedahl ???? (@jmhorp) April 25, 2022

Jayapal appears to have come up with the alleged 3.27 percent tax rate for Musk by including unrealized gains in the amount she thinks he owes taxes on (while using the standard method for calculating the average income tax rate). However, unrealized gains are, by definition, gains that Musk doesn't yet have. When he actually realizes the gains, he will be required to pay taxes on them. That's how it works.

Democrats have been itching to change the law so that unrealized gains on stocks, real estate, and other assets are taxed. (So, for instance, "a home or property that increased in value but was not sold could generate a federal tax obligation, even though the owner saw no money from the increase," as Reason's Eric Boehm recently pointed out.)

"That proposed tax is likely unconstitutional," suggests GianCarlo Canaparo, a senior legal fellow with The Heritage Foundation. With the exception of income taxes, direct taxes levied by the federal government "must be spread equally among the populations of the states to pass constitutional muster," notes Canaparo:

Income, the Supreme Court held in Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass (1955), means "undeniable accessions to wealth, clearly realized, and over which the taxpayers have complete dominion."

Tax law enthusiasts and finance gurus can quibble over whether an increase in the price of an unsold stock is an undeniable accession to wealth over which a taxpayer has complete dominion, but not even the world's best lawyer could argue that "unrealized" actually means "realized."

Another Supreme Court opinion, Eisner v. Macomber (1920), bears on that argument. There, the Supreme Court held that a stock dividend was not income because the dividend didn't put any money into the investor's hands. It was an unrealized gain because "every dollar of his investment, together with whatever accretions and accumulations have resulted … still remains the property of the company, and subject to the business risks which may result in wiping out the entire investment."

The same goes for any other unrealized capital gains, and so, they aren't income.

Defenders of wealth taxes have tried a different argument. They argue that wealth taxes are constitutional based on an opinion that predates the 16th Amendment, Knowlton v. Moore (1900). There, the court upheld an inheritance tax. Proponents of wealth taxes say inheritance taxes are the same thing.

But they aren't.

Critically, the court in Knowlton held that "[a]n inheritance tax is not one on property, but one on the succession." The court viewed the tax as attaching to the transfer of wealth.

In other words, when the money moved into the heirs' hands, the government could take its share. That's analogous to the IRS taking its share when you realize profit from selling stock. It's not analogous to the IRS demanding a share of money you don't yet have.

Or, as Sen. Joe Manchin (D–W.Va.) put it much more succinctly: "You can't tax something that's not earned. Earned income is what we're based on."

https://twitter.com/kresimirperkov2/status/1518856010760437761

Popular claims about various billionaires not paying their fair share in taxes tend to be based on the same sleight of hand Jayapal uses with Musk: calculating their tax rate based on a figure that includes unrealized gains.

Much of this is based on a ProPublica report last year which claimed that the top 25 richest Americans paid an average "true tax rate" of just 3.4 percent between 2014 and 2018 (with Musk's rate listed as 3.27 percent). This so-called "true tax rate" relied on calculations involving unrealized capital gains.

But the true tax rate "is a phony construct that exists nowhere in the law and compares how much the 'wealth' of these individuals increased from 2014 to 2018 compared to how much income tax they paid," noted the Wall Street Journal editorial board last summer:

But wealth and income are different, and what Americans pay is a tax on income, not wealth. ProPublica makes much of the fact that these billionaires pay a lower rate on capital gains and dividends than they do on income. The story suggests this is unfair, but it isn't.

The preferential rate for capital gains and dividends has been a central part of the tax code for decades, and for good reasons. Congress has wanted to encourage capital investment; assets are often held for decades and gains are only realized upon their sale; gains can't be adjusted for inflation over the years they are held; and investors can't deduct net capital losses from income beyond $3,000 a year. Bipartisan majorities have long supported this part of the tax code.

Jayapal's claim about Musk borrows this same phony construct.

Reason Editor in Chief Katherine Mangu-Ward has more here on why a wealth tax is a bad idea.

FREE MINDS

People are more likely to spread or condone misinformation if they believe it could be true at some point in the future, according to a new study published in the American Psychological Association's (APA) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. "Misinformation in part persists because some people believe it. But that's only part of the story," said lead author Beth Anne Helgason. "Misinformation also persists because sometimes people know it is false but are still willing to excuse it."

In a series of experiments involving more than 3,600 participants in total, researchers with the London Business School read statements identified as false and then asked people how likely these statements were to be true at some point. They found that people were less likely to find making false statements unethical and more likely to share them on social media if they if they believed the statement could be true eventually.

APA summarizes the findings here; the full study can be found here.

FREE MARKETS

Why aren't lawmakers taking inflation seriously?

I'm concerned and a little bit shocked at how many people have simply refused to acknowledge that demand is too high and dollars are too plentiful.https://t.co/UhPY4fiNaf pic.twitter.com/4HWbhGHWyf

— Alan Cole (@AlanMCole) April 25, 2022

QUICK HITS

Trans adults are adults and should be allowed to decide for themselves which treatments to pursue without the meddling of politicians. https://t.co/0BBWNWszq5 via @reason

— Scott Shackford (Blue Checkmark) (@SShackford) April 25, 2022

• "A New York state judge on Monday held Donald J. Trump in contempt of court for failing to comply with a subpoena from the state attorney general's office," The New York Times reports.

• The Department of Homeland Security is broken and dangerous.

• More states are limiting the use of shackles on pregnant inmates giving birth, but there's still a lot of progress to be made, reports NPR. Last week, Tennessee's legislature became the latest state to limit the practice; the bill awaits the governor's signature.

• A new study challenges popular notions about YouTube and extremism, writes Reason's Liz Wolfe.