L.A. Considers Honoring Civil Rights-Era Housing Activist by Making It Harder To Build Housing

Preservationists hope to make the one-time home of Loren Miller a historic landmark. That it would make it nearly impossible to redevelop the $1.4 million two-bedroom home.

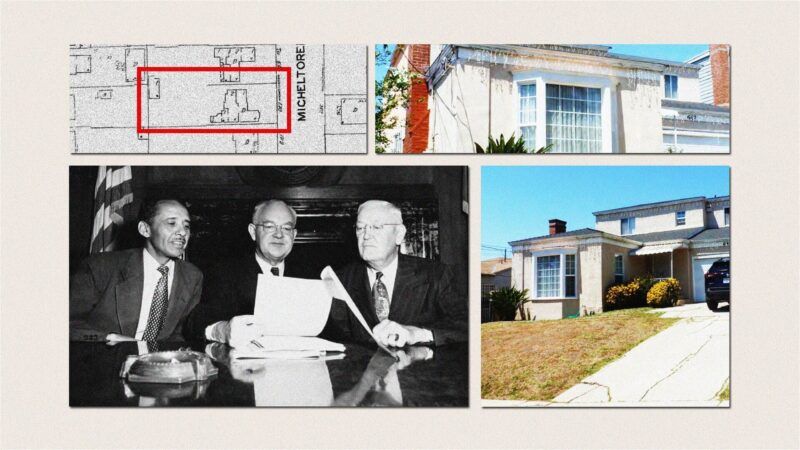

Loren Miller was a crusading civil rights activist and lawyer who upended racist restrictions on black people owning homes. Los Angeles preservationists want to honor his legacy by preventing the redevelopment of a single-family home he once lived in.

On Thursday, Los Angeles's Cultural Heritage Commission (CHC) voted to take up an application from preservationist Teresa Grimes to landmark a two-story, two-bedroom house in the city's Silver Lake neighborhood that Miller lived in from 1940 until his death in 1967.

It was during that time, per the application, that Miller worked on a number of landmark civil rights lawsuits.

That includes his work successfully defending black homeowners in Los Angeles' Sugar Hills neighborhood who'd been sued by their white neighbors for violating expired restrictive covenants that barred the sale of homes to non-whites. Later, Miller was a co-counsel, alongside future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, on the landmark 1948 Supreme Court case Shelley v Kraemer, in which the Court ruled that government enforcement of racially restrictive covenants was unconstitutional.

His work on housing issues earned Miller a reputation as a leading legal light of the civil rights movement. Curbed says he was dubbed "Mr. Civil Rights." Less august is his modest Silver Lake home, a fact that commissioners candidly acknowledged at Thursday's hearing.

"The architecture isn't the governing factor. I don't think any of us would say this is architecturally significant," said CHC Commission President Barry Milofsky. Nevertheless, Milofsky said the history that happened inside the home "needs to be recognized, commemorated, and memorialized."

Representatives of the L.A. Conservancy and the Silver Lake Heritage Trust both spoke in favor of landmarking Miller's former home at the meeting as well.

Absent from the proceedings were Edgar and Eugenia Gonzalez, which commission documents list as the current owners of the house through a family trust. Should the Miller house be successfully landmarked, the couple's rights as property owners to alter or redevelop it will be severely constrained.

(Commission staff said on Thursday that the Gonzalezs had been notified of the hearing. Grimes also said she reached out to the owners prior to filing the landmarking application but received no reply.)

L.A. law requires demolition permits for "Historic-Cultural Monuments"—something that would be needed if one wanted to redevelop the property—to be reviewed by the heritage commission. The commission can also choose to delay the issuance of those permits by up to 180 days (or 360 days with city council approval).

An FAQ from the city's Office of Historic Resources also says that monuments are presumed to be a historic resource under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), meaning any application for a demolition permit might require the preparation of an Environmental Impact Report.

Those reports can take years to complete and often require expensive studies costing tens of thousands of dollars (or more). Third parties are also empowered to sue if they believe an environmental impact report wasn't thorough enough, which can stretch things out for even longer.

All of that would obviously be a major barrier to redeveloping the Miller home into a duplex or triplex, something that's allowed by the property's zoning. On property rights grounds alone, that's a reason to oppose historic preservation laws that don't require the owner's consent (which L.A.'s doesn't).

Preventing that redevelopment appears to be a partial motivation for landmarking Miller's old home. On the section of the application where one is supposed to list physical threats to the property, Grimes just wrote "zoning."

There's a particular irony in the possibility that Los Angeles officials might impose these restrictions on a home once owned by Miller.

Redeveloping his one-time home, which Redfin lists at $1.4 million, into a multi-unit development would allow several families to split those high land costs between them—making the property more affordable to more people.

The potential for two- and three-unit homes to be cheaper than the single-family homes they replace is why a number of city councils and state legislatures have passed or proposed legalizing this kind of "missing middle" housing.

When doing so, zoning reform proponents often note the racist legacy of "exclusionary" single-family-only zoning. By making neighborhoods more affordable, they argue, you'll make them more racially diverse and inclusive as well.

But landmarking a house once owned by Miller—who spent his career agitating for more inclusive housing—would make it much more difficult for its owners to convert it into this kind of more inclusive housing if they wanted to. Preserving the physical structure he lived in seems to violate the animating purpose of his work.

The CHC has until mid-May to vote on whether to landmark Miller's home. If approved, it then goes to the city council for a final vote.