Tucson Handyman Gets His Jeep Back After He Threatens to Fight the Forfeiture

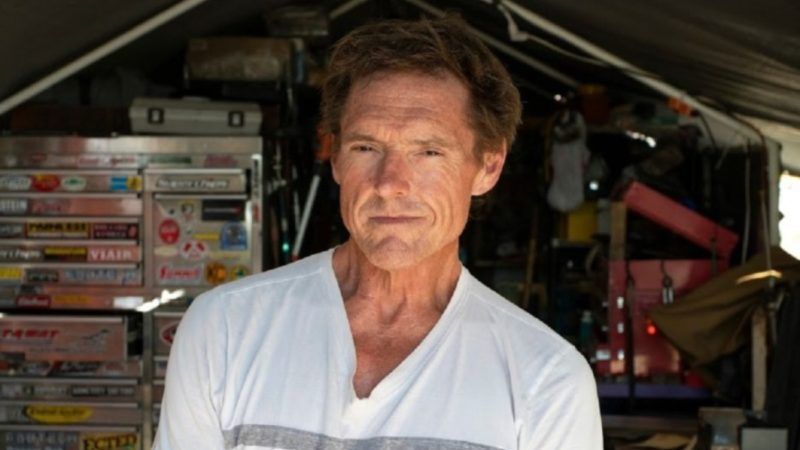

The cops seized Kevin McBride's $15,000 car because his girlfriend allegedly used it for a $25 marijuana sale.

What happens when innocent people stand up to government bullies who use civil forfeiture laws to steal their property? In many cases, the bullies, unaccustomed to such resistance, fold like a cheap suit. That is what happened today in Tucson, where the government returned Kevin McBride's Jeep, which police seized in May after his girlfriend allegedly used it for a $25 marijuana sale.

Until last Friday, the Pima County Attorney's Office was demanding a $1,900 ransom for the safe return of McBride's lovingly restored Jeep, saying "an outright return of the vehicle is inappropriate in this case." But the day after the Goldwater Institute threatened to sue on McBride's behalf, arguing that Arizona's civil forfeiture law unconstitutionally requires property owners to prove their innocence, prosecutors changed their tune.

"Upon inquiry pursuant to A.R.S. § 13-4309(3)(a) & (b), remission is declared," says a letter dated August 21 from Deputy County Attorney Kevin Krejci, the same official who told McBride in an August 11 letter that he would have to pay $1,900 under a "mitigation" agreement to get his Jeep back. "The 2000 JEEP WRANGLER…is released from seizure for forfeiture. The seizing agency and any person holding property for the seizing agency are hereby authorized to arrange the release of the seizure for forfeiture on this property."

Goldwater Institute spokesman Mike Brownfield says "there was no explanation given." But I will go out on a limb and suggest that the government's swift reversal has something to do with the negative publicity and legal risk generated by a case like this one, in which McBride lost his only means of transportation and the basis of his livelihood as a handyman because he let his girlfriend take his Jeep to a convenience store so she could fetch him a cold soda while he was working. The cops claim she then sold marijuana to an undercover officer for $25. Although the charges against her were dropped, the Jeep remained in custody, accused of participating in criminal activity, because that is how civil forfeiture works.

Arizona law would have allowed McBride to challenge the forfeiture by arguing that he "did not know and could not reasonably have known" about the alleged illegal use of his property. But the burden would have been on him to prove that, and it would have required spending thousands of dollars on a lawyer, with no guarantee of winning, if the Goldwater Institute had not agreed to represent him for free. Law enforcement agencies count on those barriers when they extort money from innocent property owners like McBride, who naturally tend to give up when they discover that fighting the forfeiture will cost more than the bribe demanded by the government's lawyers, and in many cases more than the property is worth.

Did I mention that Arizona law enforcement agencies get to keep 100 percent of the proceeds from the forfeitures they handle? If the government sold the Jeep for $15,000 (which is what McBride estimates it is worth), local cops and prosecutors would have split the money. Even without risking a legal challenge, they would have gotten $1,900 for the price of a letter if McBride had done the sensible thing by surrendering. Multiply those ill-gotten gains by all the seizures that happen in Arizona, and you've got nearly $30 million to pad law enforcement budgets each year, a consideration that tends to warp policing priorities. While the public safety payoff from seizures like this one is zero, the profit adds up.

"Kevin isn't the only person who's been targeted by civil asset forfeiture schemes—and unfortunately, he probably won't be the last," says Goldwater Institute senior attorney Matt Miller. "The Goldwater Institute will continue to put pressure on states to reform or repeal these unfair laws—whether through legal action or through state legislatures amending these laws to require a criminal conviction."

[This post has been revised to clarify the timing of Krejci's letter.]