Former Time Editor and CEO of Constitution Center (!) Wants To Cancel First Amendment, Pass Hate Speech Laws

Freedom of expression is under attack from politicians, activists, and, saddest of all, journalists who benefit most from it.

If you need more proof that free expression is under serious and sustained attack, look no further than The Washington Post, that legendary and often self-congratulatory bastion of First Amendment support, which has just published an op-ed calling for hate speech laws because "on the Internet, truth is not optimized. On the Web, it's not enough to battle falsehood with truth; the truth doesn't always win."

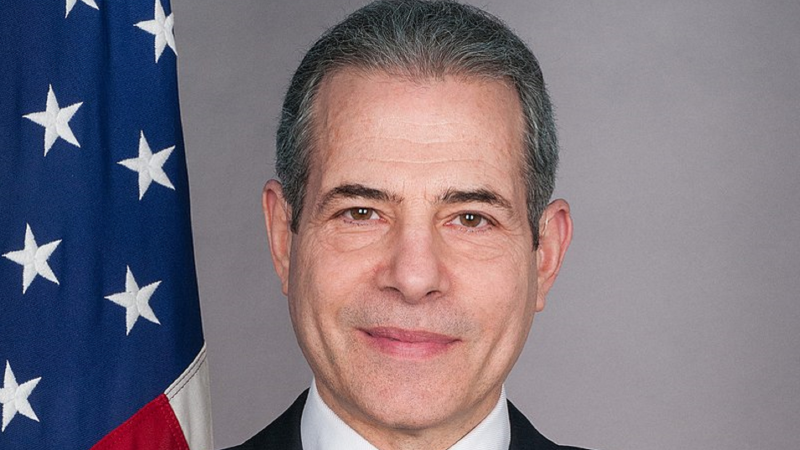

What's even more disheartening is that the author is Richard Stengel, a former managing editor of Time, chairman of the National Constitution Center, and Obama-era State Department official whose soul-searching apparently began when challenged by diplomats from a part of the world notorious for particularly brutal forms of censorship. As a journalist, Stengel avers, he loved, loved, loved the First Amendment and its commitment to free speech. But then he got stumped by unnamed representatives of unnamed governments who asked banal questions:

Even the most sophisticated Arab diplomats that I dealt with did not understand why the First Amendment allows someone to burn a Koran. Why, they asked me, would you ever want to protect that?

Is he kidding? "Why would a country founded in large part on the Enlightenment values of free speech and religious freedom allow free speech and religious freedom?" doesn't seem like a tough question to answer. He doesn't name the countries his "most sophisticated Arab diplomats represented, so we need to fill that detail in. Let's assume they were from Saudi Arabia, a country completely unworthy of emulation when it comes to respecting basic human rights and whose Prince Mohammed bin Salman has taken responsibility for the brutal torture and murder of Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi. We allow the burning of the Koran for the same reasons we allow the burning of King James and St. Jerome Bibles, the desecration of the U.S. flag, and the potential libeling of elected officials: We believe that individuals have rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. With a few exceptions such as "fighting words," "true threats," and obscenity, we know that it's better to allow more speech rather than less. Surprisingly, people get along better when they can more freely speak their minds. The search for "truth"—or at least consensus—benefits from free expression, too, as ideas and attitudes are subjected to examination from friends and foes alike. But the pragmatic answer is ultimately secondary to the expressive one: We allow free speech because no one, certainly not the government, has a right to curtail it.

As befits a man who helmed a legacy media outlet that is slowly being reduced to rubble like a statue of Ozymandias in the desert, Stengel is particularly distraught over "the Internet" and the "Web." He implies that the "marketplace of ideas" worked well enough when John Milton and, a bit later, America's founders pushed an unregulated press, but, well, times have changed.

On the Internet, truth is not optimized. On the Web, it's not enough to battle falsehood with truth; the truth doesn't always win. In the age of social media, the marketplace model doesn't work. A 2016 Stanford study showed that 82 percent of middle schoolers couldn't distinguish between an ad labeled "sponsored content" and an actual news story. Only a quarter of high school students could tell the difference between an actual verified news site and one from a deceptive account designed to look like a real one.

If you're basing the erosion of constitutional rights on the reading comprehension skills of middle schoolers, you're doing it wrong. And by it, I mean journalism, constitutional analysis, politics, and just about everything else, too.

Stengel pivots from discussing truth in media to "hate speech," a ridiculously expansive term he never defines with precision (he even writes, "there's no agreed-upon definition of what hate speech actually is"). But because mass shooters such as Dylann Roof, Omar Mateen, and the El Paso shooter "were consumers of hate speech," it's time to chuck out hard-fought victories that allow individuals and groups to express themselves in words and pictures. Hate speech, laments Stengel, doesn't just cause violence (though strangely, violence is declining even as social media is flourishing), it also

diminishes tolerance. It enables discrimination. Isn't that, by definition, speech that undermines the values that the First Amendment was designed to protect: fairness, due process, equality before the law? Why shouldn't the states experiment with their own version of hate speech statutes to penalize speech that deliberately insults people based on religion, race, ethnicity and sexual orientation?

All speech is not equal. And where truth cannot drive out lies, we must add new guardrails. I'm all for protecting "thought that we hate," but not speech that incites hate. It undermines the very values of a fair marketplace of ideas that the First Amendment is designed to protect.

A quick reading of the First Amendment would have reminded Stengel—the former chairman and CEO of the National Constitution Center, fer chrissakes!—that the First Amendment isn't about limiting speech that bothers the sensibilities of people. It's actually all about Congress not making laws that would create an official religion or restricting individual speech and freedom of the press; it also guarantees that we have the right of assembly and petition. The values it reflects involve pluralism and tolerance, not shutting down, regulating, or restricting speech that makers of "new guardrails" find offensive, annoying, or inconvenient.

If you grew up any time in the past 60 years or so, you've taken freedom of speech for granted. That's due to a series of legal rulings that struck down the ability of elected officials to strangle speech they didn't like, ranging from potentially libelous personal attacks to once-banned literary works as Lady Chatterley's Lover, Howl, and Ulysses, along with materials such as the Pentagon Papers and the rise of technology that made producing and consuming all sorts of texts, images, music, video, and other forms of creative expression vastly easier.

It's incredibly dispiriting to see baby boomers like Stengel brush aside the incredible wins in free expression because of concerns about vaguely defined terms such as "hate speech." He gives off a strong whiff of internet and Cold War paranoia—"Russian agents assumed fake identities, promulgated false narratives and spread lies on Twitter and Facebook, all protected by the First Amendment"—that seems widely shared by his generational peers. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) is an increasingly strong presidential candidate who has vowed to regulate explicitly political speech, especially its online iterations:

If we can lie in Facebook ads and get away with it, we know that campaign finance laws are not equipped to address online political advertising. My plan would modernize campaign finance law for the digital age. If you are ready to regulate political ads on the internet, sign up.

— Elizabeth Warren (@ewarren) October 15, 2019

Older boomers are syncing with millennials and younger Americans, who show a strong predilection to limiting "bad" speech (a 2015 Pew survey found 40 percent of millennials supported censoring "offensive statements about minorities"). These are not good developments, and neither is an op-ed in The Washington Post calling for an effective revocation of the First Amendment. Throw in bipartisan interest in regulating social media platforms as public utilities, the president's interest in "opening up" the libel laws so he can more easily sue his critics, the rise of "cancel culture," and we're one Zippo lighter short of a good, old-fashioned book burning.