Russian Researcher Plans To Gene-Edit Embryos To Cure Deafness

Is that kind of gene-editing unethical?

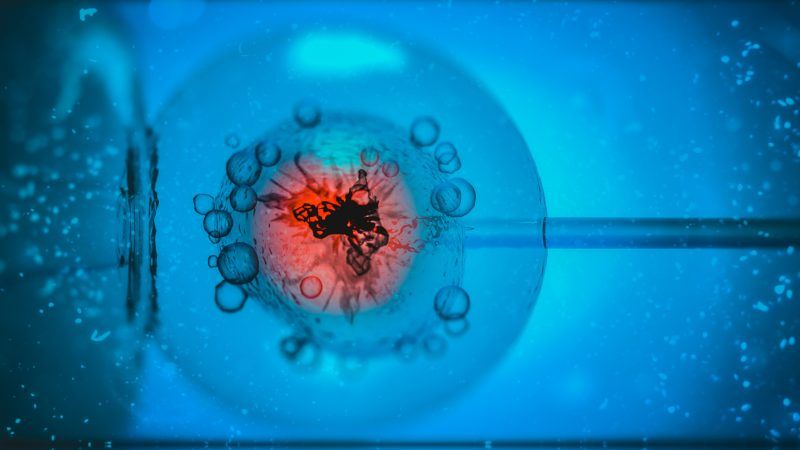

Five congenitally deaf couples have agreed to allow their embryos to be edited by Russian biologist Denis Rebrikov, who will use CRISPR to correct the defective GJB2 genes that are responsible for their hearing loss. Since both would-be parents harbor two copies of the gene, their children would necessarily also be deaf.

So far as is known, CRISPR gene-editing of human embryos has only been done by Chinese biophysicist He Jiankui. He announced the birth in November of two girls whose genomes he had edited using CRISPR with the goal of making them immune to the HIV/AIDS virus. He was widely denounced for conducting an unethical and risky treatment. Some of the condemnations were justified: The technique's safety is unknown and the babies' parents likely were not provided with enough information to give truly informed consent. Despite being reproached for ethical lapses, He has reportedly been approached quietly by several fertility clinics that are interested in offering gene-editing services to their clients.

Since the hearing loss versions of the GJB2 gene are recessive, Rebrikov aims to use CRISPR to correct one version of the GJB2 genes, thus enabling the gene-edited child to hear. Earlier this month, researchers at Harvard using CRISPR successfully edited a mouse gene associated with hearing loss.

One of the chief safety concerns with CRISPR is the possibility of off-target mutations that could result in unintended harms to gene-edited babies. In other words, there is the risk of editing a gene you don't intend to, producing results you also don't intend. However, performing the edit at the one-cell stage enables reproductive clinicians to excise and test cells taken at a later stage of embryonic development to make sure the edit has been properly made and that no dangerous off-target mutations have occurred.

Many of He's critics point out that there are now effective ways to treat and prevent HIV/AIDS—including a possible vaccine—without resorting to gene-editing. Similarly, it is possible to correct hearing loss through the use of a cochlear implant device. It is worth noting that, in the United States, the cochlear implant devices and associated treatments can cost up to $100,000. Although gene-editing would obviously involve additional costs, the price of one cycle of IVF treatments is around $8,000 in Russia and about $12,000 in the U.S.

Hearing loss is not a fatal disease and obviously many deaf folks live happy and fulfilling lives. So should Rebrikov be allowed to proceed with his gene-editing plans? Assuming adequate safety precautions are in place and that parents clearly understand the risks and benefits from the proposed treatments, the answer is yes.